[/caption]

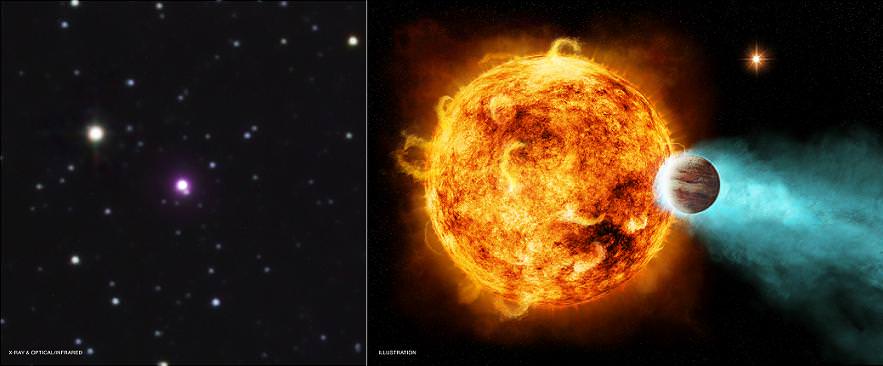

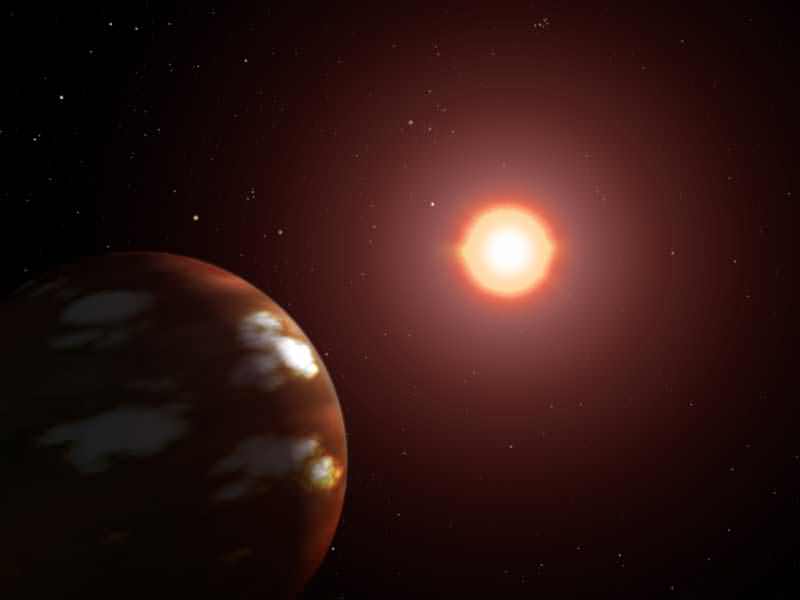

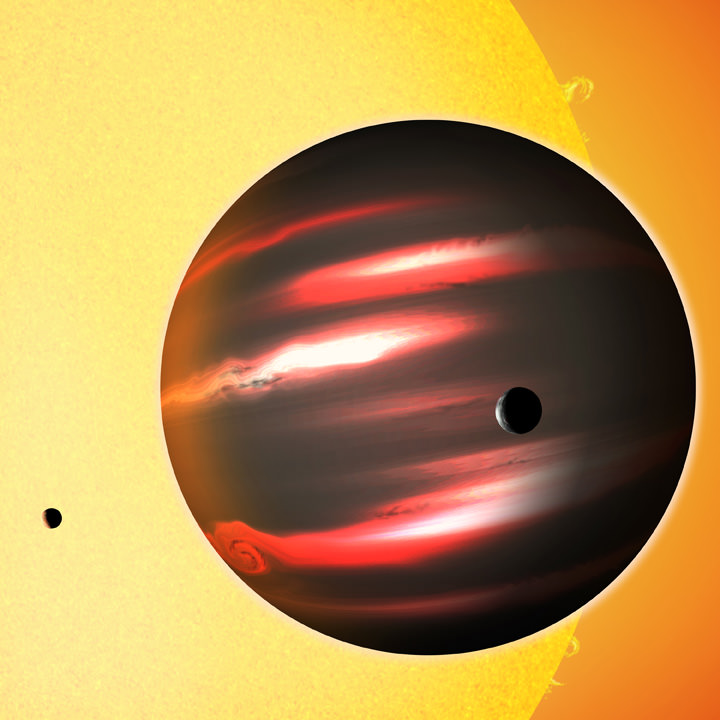

Some 880 light years away, a star named CoRoT-2a is busy decimating one of its planets – CoRoT-2b. Orbiting the parent star at a distance of over two million miles is dangerous business in this cosmic neighborhood. While the intrepid exoplanet might be about a thousand times the size of Earth right now, it’s getting about five million tons of matter stripped away from it every second. Thanks to new data from NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory and the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope, we’re able to take a closer look at this high-energy process for an even better understanding of how planets may – or may not – survive the process of forming a solar system.

“This planet is being absolutely fried by its star,” said Sebastian Schroeter of the University of Hamburg in Germany. “What may be even stranger is that this planet may be affecting the behavior of the star that is blasting it.”

Discovered by the French Space Agency’s Convection, Rotation and planetary Transits (CoRoT) satellite in 2008, this hot system is estimated to be between about 100 million and 300 million years old. The active parent star is assumed to be completely formed, yet its high magnetic activity is producing a bright x-ray signature comparable to that of a younger star. What could be causing the deviation that racks CoRoT-2b with a hundred thousand times more radiation than we receive from Sol?

“Because this planet is so close to the star, it may be speeding up the star’s rotation and that could be keeping its magnetic fields active,” said co-author Stefan Czesla, also from the University of Hamburg. “If it wasn’t for the planet, this star might have left behind the volatility of its youth millions of years ago.”

However, CoRoT-2a might not be alone. There’s a possibility that it’s a binary system with the companion positioned at roughly a thousand AU. If so, why can’t the x-ray instruments detect it? The answer is… it is not feeding on a planet to keep it active. CoRoT-2b’s huge size and proximity make for an intriguing combination. For as long as it lasts…

“We’re not exactly sure of all the effects this type of heavy X-ray storm would have on a planet, but it could be responsible for the bloating we see in CoRoT-2b,” said Schroeter. “We are just beginning to learn about what happens to exoplanets in these extreme environments.”

Original Story Source: Chandra News. For further reading: The corona and companion of CoRoT-2a. Insights from X-rays and optical spectroscopy.