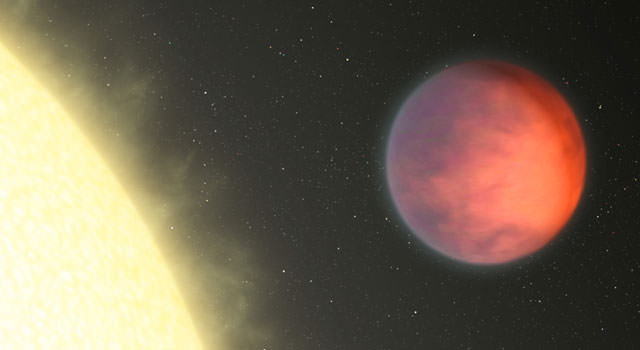

At best, the few extrasolar planets we have imaged directly are just points of light. But what can that light tell us about the planet? Maybe more than we thought. As you probably know the, Deep Impact spacecraft flew by comet Hartley 2 today, taking images from only 700 km away. But maneuvering to meet up with the comet is not the only job this spacecraft has been doing. The EPOXI mission also looked for ways to characterize extrasolar planets and the team made a discovery that should help identify distinctive information about extrasolar planets. How did they do it? By using the Deep Impact spacecraft to look at the planets in our very own solar system.

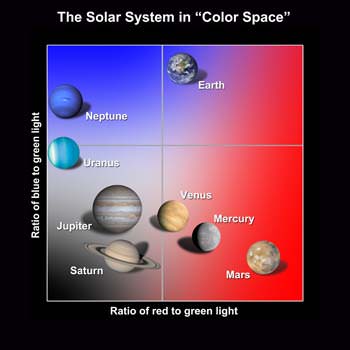

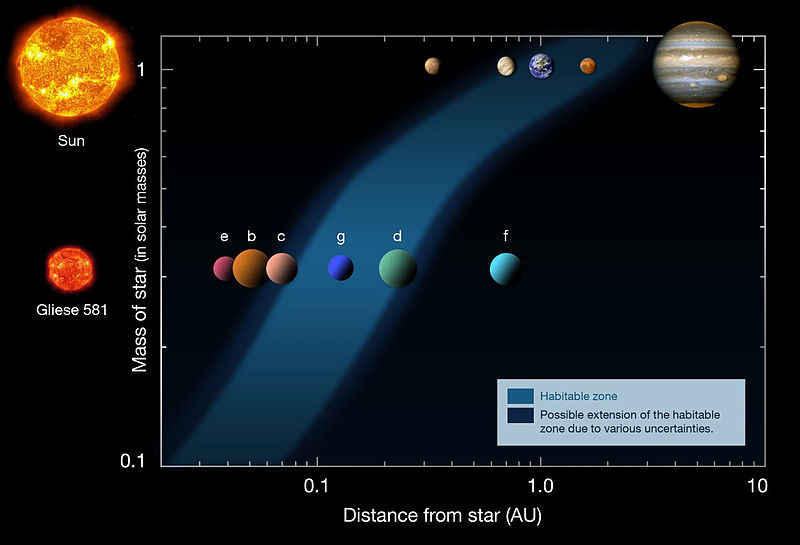

The spacecraft imaged the planetary bodies in our solar system — in particular the Earth, Mars and our Moon — (see here for movies of the Moon transiting Earth) and astronomer Lucy McFadden and UCLA graduate Carolyn Crow compared the reflected red, blue, and green light and grouped the planets according to the similarities they saw. The planets fall into very distinct regions on this plot, where the vertical direction indicates the relative amount of blue light, and the horizontal direction the relative amount of red light.

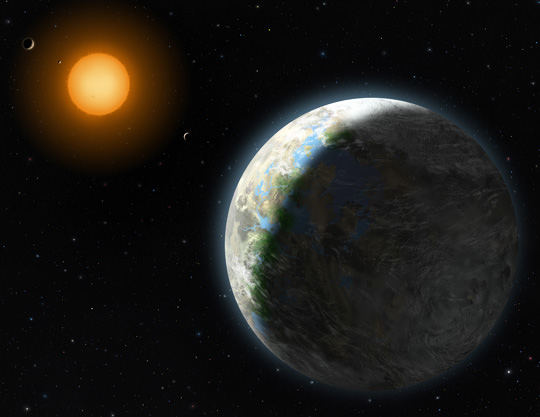

This suggests that when we do have the technology to gather light from individual exoplanets, astronomers could use color information to identify Earth-like worlds. “Eventually, as telescopes get bigger, there will be the light-gathering power to look at the colors of planets around other stars,” McFadden says. “Their colors will tell us which ones to study in more detail.”

On the plot, the planets cluster into groups based on similarities in the wavelengths of sunlight that their surfaces and atmospheres reflect. The gas giants Jupiter and Saturn huddle in one corner, Uranus and Neptune in a different one. The rocky inner planets Mars, Venus, and Mercury cluster off in their own corner of “color space.”

But Earth really stands out, and its uniqueness comes from two factors. One is the scattering of blue light by the atmosphere, called Rayleigh scattering, after the English scientist who discovered it. The second reason Earth stands out in color is because it does not absorb a lot of infrared light. That’s because our atmosphere is low in infrared-absorbing gases like methane and ammonia, compared to the gas giant planets Jupiter and Saturn.

“It is Earth’s atmosphere that dominates the colors of Earth,” Crow says. “It’s the scattering of light in the ultraviolet and the absence of absorption in the infrared.”

So, this filtering approach could provide a preliminary look at exoplanet surfaces and atmospheres, giving us an inkling of whether the planet is rocky or a gas planet, or what kind of atmosphere it has.

EPOXI is a combination of the names for the two extended mission components for the Deep Impact spacecraft: the first part of the acronym comes from EPOCh, (Extrasolar Planet Observations and Characterization) and the flyby of comet Hartley 2 is called the Deep Impact eXtended Investigation (DIXI).