[/caption]

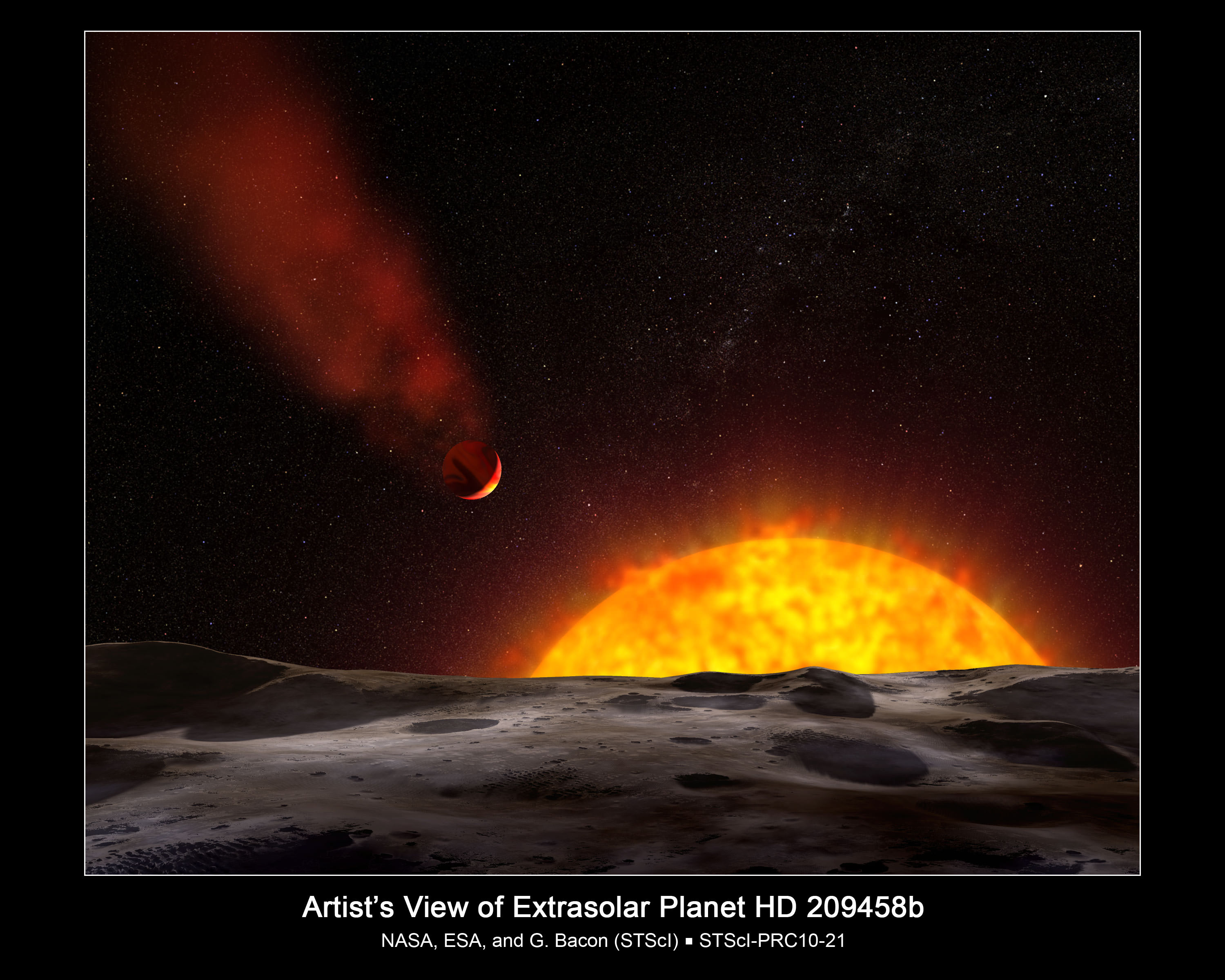

We truly live in an amazing time for exoplanet research. It was only 18 years ago the first planet outside our solar system was discovered. Fifteen since the first confirmation of one around a main sequence star. Even more recently, direct images have begun to sprout up, as well as the first spectra of the atmospheres of such planets. So much data is becoming available, astronomers have even begun to be able to make inferences as to how these extra solar planets could have formed.

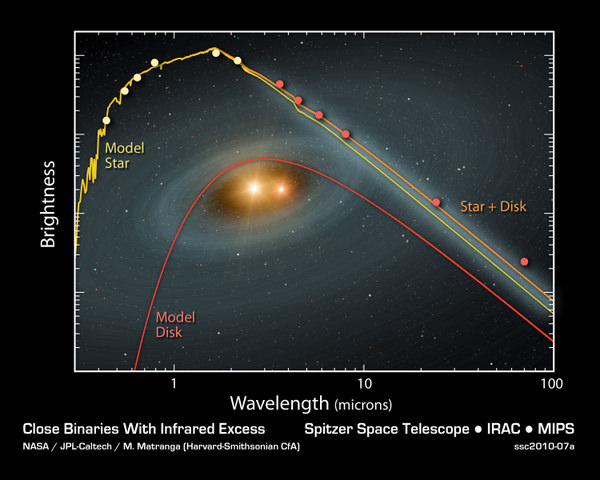

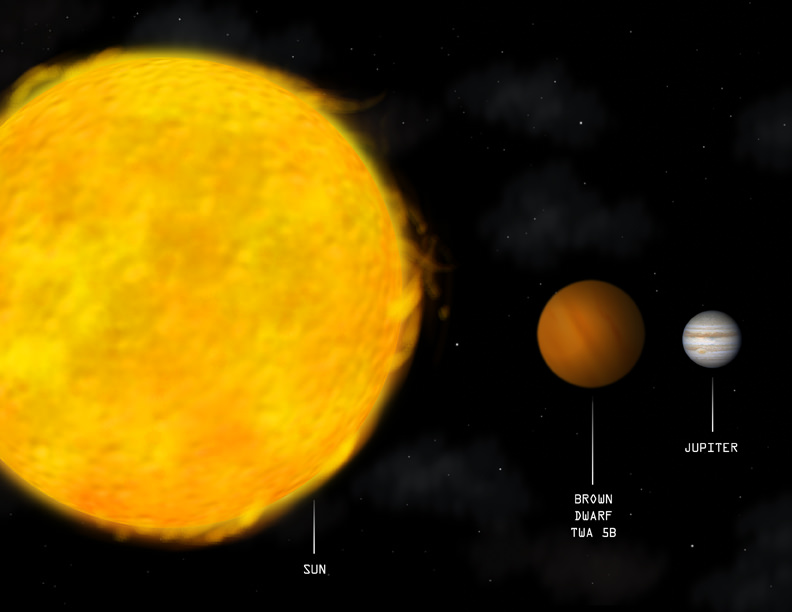

In general, there are two methods by which planets can form. The first is via coaccretion in which the star and the planet would form from gravitational collapse independently of one another, but in close enough proximity that their mutual gravity binds them together in orbit. The second, the method through which our solar system formed, is the disk method. In this, material from a thin disk around a proto-star collapses to form a planet. Each of these processes has a different set of parameters that may leave traces which could allow astronomers to uncover which method is dominant. A new paper from Helmut Abt of Kitt Peak National Observatory, looks at these characteristics and determines that, from our current sampling of exoplanets, our solar system may be an oddity.

The first parameter that distinguishes the two formation methods is that of eccentricity. To establish a baseline for comparison, Abt first plotted the distribution of eccentricities for 188 main-sequence binary stars and compared that to the same type of plot for the only known system to have formed via the disk method (our Solar System). This revealed that, while the majority of stars have orbits with low eccentricity, this percentage falls off slowly as the eccentricity increases. In our solar system, in which only one planet (Mercury) has an eccentricity greater than 0.2, the distribution falls off much more steeply. When Abt constructed the distribution for the 379 planets with known eccentricity, it was nearly identical to that for binary stars.

A similar plot was created for the semi major axis of binary stars and our solar system. Again, when this was plotted for the known extra solar planets the distribution was similar to that of binary star systems.

Abt also inspected the configuration of the systems. Star systems containing three stars generally contained a pair of stars in a tight binary orbit with a third in a much larger orbit. By comparing the ratios of such orbits, Abt quantified the orbital spacing. However, instead of simply comparing to the solar system, he considered the analogous situation of formation of stars around the central mass of the galaxy and built a similar distribution in this manner. In this case, the results were ambiguous; Both modes of formation produced similar results.

Lastly, Abt considered the amount of heavy elements in the more massive body. It is widely known that most extra-solar planets are found around metal-rich stars. While there’s no reason planets forming in a disk couldn’t be formed around high mass stars, having a metal-rich cloud from which to form stars and planets is a requirement for the coaccretion model because it tends to accelerate the collapse process, allowing giant planets to fully form before the cloud was dissipated as the star became active. Thus, the fact that the vast majority of extra-solar planets exist around metal-rich stars favors the coaccretion hypothesis.

Taken together, this provides four tests for formation models. In every case, current observations suggest that the majority of planets discovered thus far formed from coaccretion and not in a disc. However, Abt notes that this is most likely due to statistical biases imposed by the sensitivity limits of current instruments. As he notes, astronomers “do not yet have the radial velocity sensitivity to detect disk systems like the solar system, except for single large planets, like Jupiter at 5 AU.” As such, this view will likely change as new generations of instruments become available. Indeed, as instruments improve to the point that three dimensional mapping becomes available, and orbital inclinations can be directly observed, astronomers will be able to add another test to determine the modes of formation.

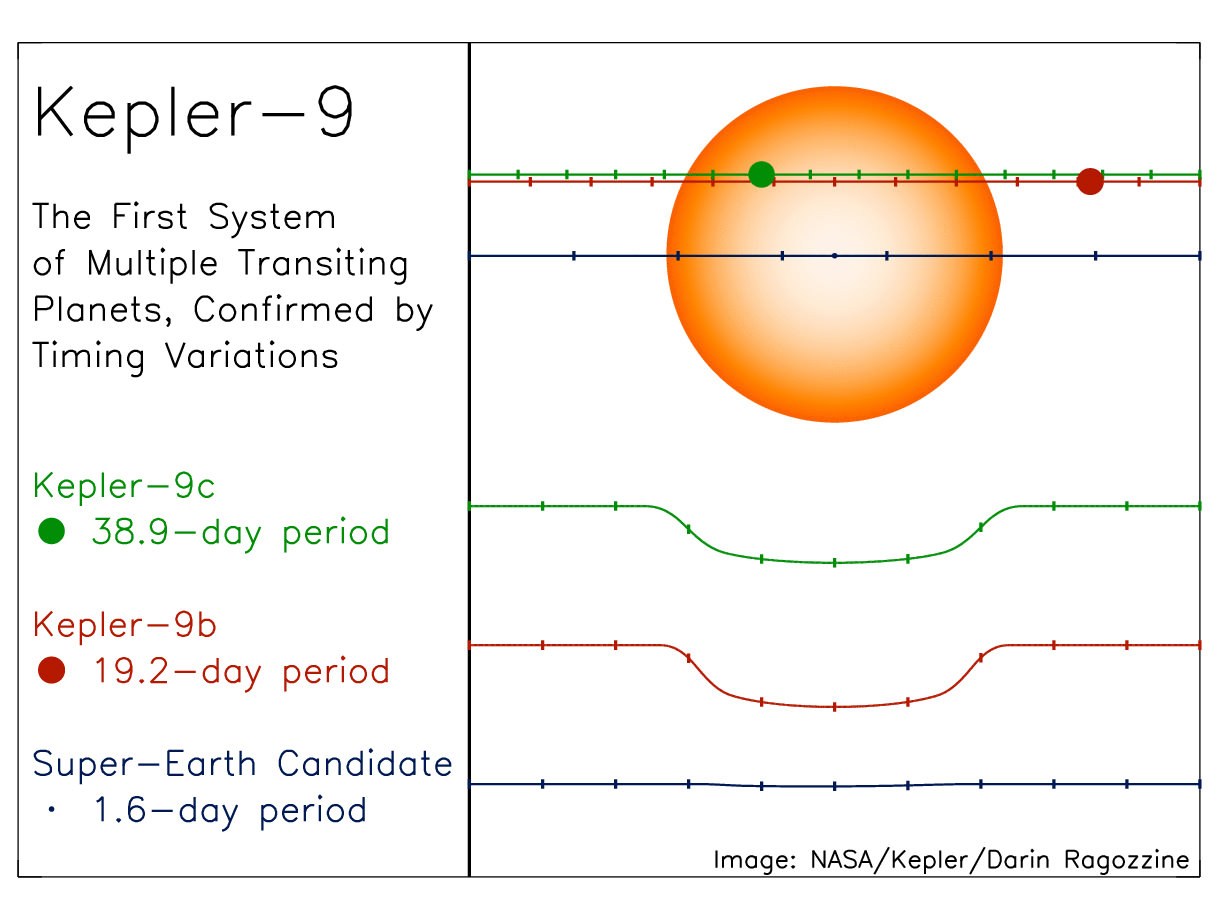

EDIT: Following some confusion and discussion in the comments, I wanted to add one further note. Keep in mind this is only the average of all systems currently known that looks like coaccreted systems. While there are undoubtedly some in there that did form from disks, their rarity in the current data makes them not stand out. Certainly, we know of at least one system that fits a strong test for the disk method. This recent discovery by Kepler, in which three planets have been observed transiting their host star demonstrates that all of these planets must lie in a disk which does not conform to expectations of independent condensation. As more systems like this are discovered, we expect that the distributions of the tests described above will become bimodal, having components that match each formation hypothesis.