In 1948-49, mathematician, physicist, computer scientist, and engineer John von Neumann introduced the world to his idea of “Universal Assemblers,” a species of self-replicating robots. Von Neumann’s ideas and notes were later compiled in a book titled “Theory of self-reproducing automata,” published in 1966 (after his death). In time, this theory would have implications for the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence (SETI), with theorists stating that advanced intelligence must have deployed such probes already.

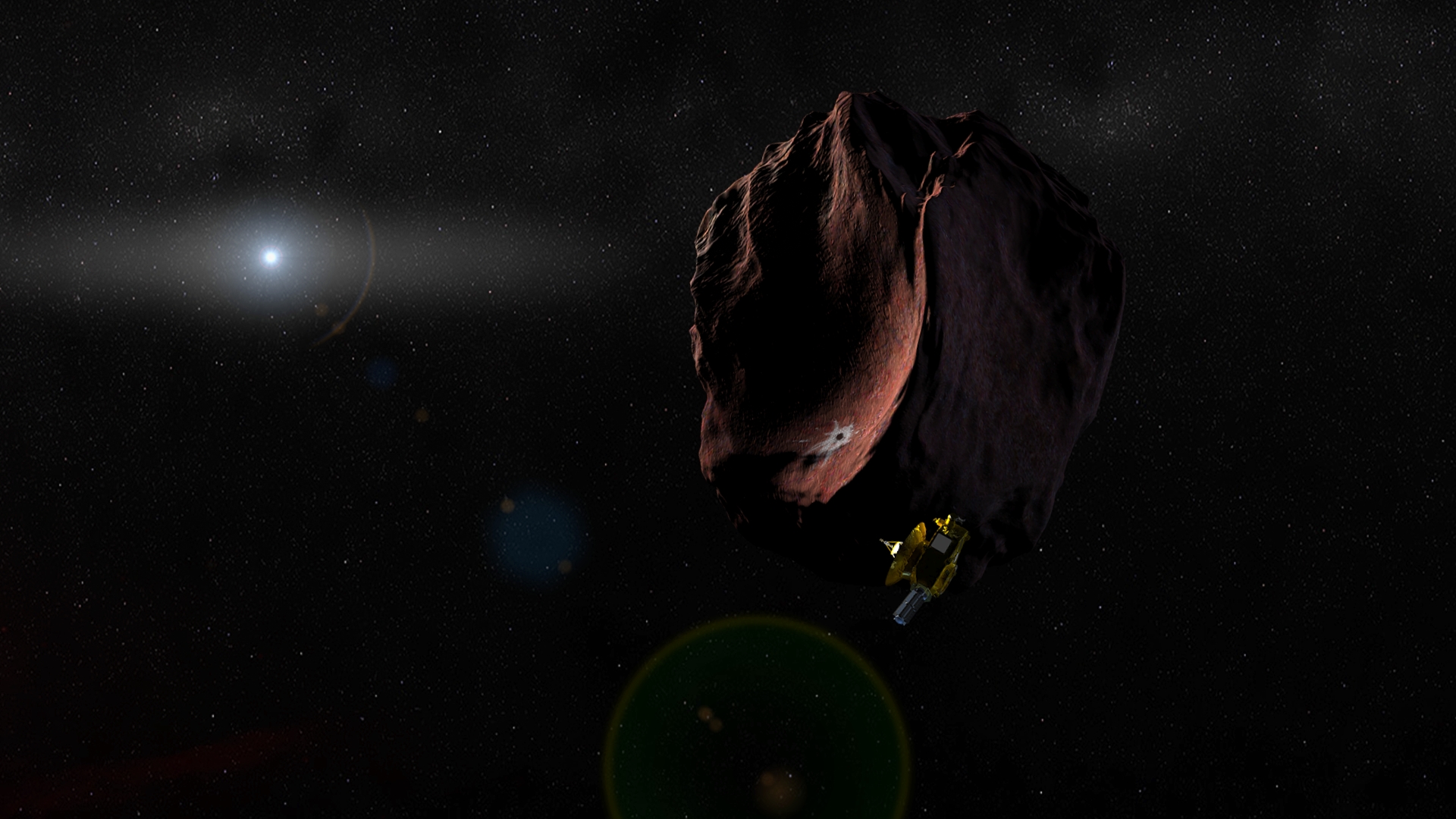

The reasons and technical challenges of taking the self-replicating probe route are explored in a recent paper by Gregory L. Matloff, an associate professor at the New York City College of Technology (NYCCT). In addition to exploring why an advanced species would opt to explore the galaxy using Von Neumann probes (which could include us someday), he explored possible methods for interstellar travel, strategies for exploration, and where these probes might be found.

Continue reading “Why Would an Alien Civilization Send Out Von Neumann Probes? Lots of Reasons, says a new Study”