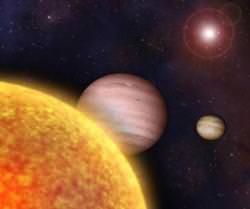

NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope has measured huge quantities of water and organic compounds surrounding the star AA Tauri, 450 light years from Earth. AA Tauri is a young star, only a million years old, not too dissimilar to our Sun when it was a baby. What makes AA Tauri even more special is that it appears to have the “spectral fingerprint” for a system that could allow life to form. Finding a star system similar to our own, with organic compounds was always bound to cause excitement, but finding a star so close to us provides a fantastic opportunity to study AA Tauri. This will, in turn, help us understand the evolution of our own solar system and how life is able to form…

AA Tauri is slowly evolving. Gas and dust surrounds the star and recent observations suggest there are abundant organic chemicals (the ones responsible for binding together and creating amino acids). Although NASA’s announcement isn’t claiming that ET is out there (you can sit back into your seats), it is significant that a star should have all the building blocks for life as we know it laid out for the spectrometer on board Spitzer to observe.

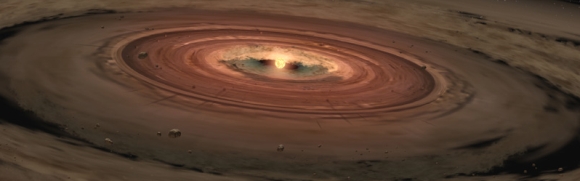

The basic organic chemicals in question are possibly located within the “Goldilocks Zone” for planetary/life development from AA Tauri. Although AA Tauri is young, the surrounding flat disk of planetary-forming materials should eventually coalesce to form rocky bodies such as planets, asteroids and possibly gas giants (along the lines of “failed star” Jupiter). The abundance of organic chemicals and water will add to the intrigue surrounding the star.

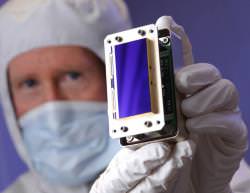

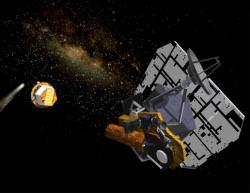

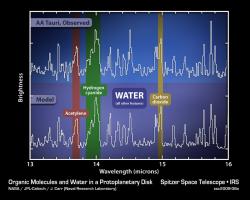

These observations were collected by NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope which is able to probe deep into the chemical structure of stars hundreds of parsecs from Earth. John Carr (Naval Research Laboratory, Washington) and Joan Najita (National Optical Astronomy Observatory, Tucson, Ariz.) are developing a new technique, applying Spitzer’s infrared spectrograph. The spectrograph is able to read the chemical composition of the dust contained within a protoplanetary disk. The team has been able to push Spitzer to a new level of precision by analysing the chemical composition of dust particles rather than the gas surrounding the star.

“Most of the material within the disks is gas, but until now it has been difficult to study the gas composition in the regions where planets should form. Much more attention has been given to the solid dust particles, which are easier to observe.” – John Carr of the Naval Research Laboratory, Washington.

So far abundances of hydrogen cyanide, acetylene, carbon dioxide and water vapour have been discovered, allowing scientists to see whether these organic chemicals are enriched or lost during the violent period of planetary formation. Observations such as these highly accurate measurements allow us a chance to glimpse back in time to see what our protoplanetary solar system may have looked like, clearly a very exciting time for the quest to find the origins of life in our galaxy.

Source: NASA/JPL