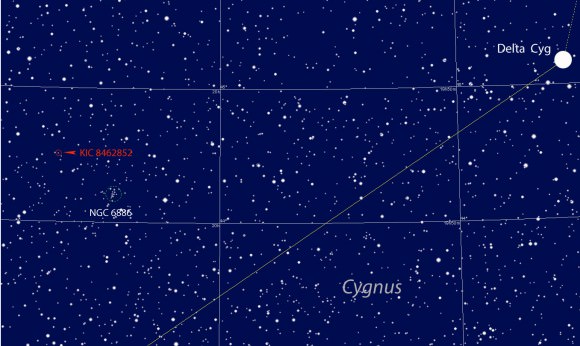

Last fall, astronomers were surprised when the Kepler mission reported some anomalous readings from KIC 8462852 (aka. Tabby’s Star). After noticing a strange and sudden drop in brightness, speculation began as to what could be causing it – with some going so far as to suggest that it was an alien megastructure. Naturally, the speculation didn’t last long, as further observations revealed no signs of intelligent life or artificial structures.

But the mystery of the strange dimming has not gone away. What’s more, in a paper posted this past Friday to arXiv, Benjamin T. Montet and Joshua D. Simon (astronomers from the Cahill Center for Astronomy and Astrophysics at Caltech and the Carnegie Institute of Science, respectively) have shown how an analysis of the star’s long-term behavior has only deepened the mystery further.

To recap, dips in brightness are quite common when observing distant stars. In fact, this is one of the primary techniques employed by the Kepler mission and other telescopes to determine if planets are orbiting a star (known as Transit Method). However, the “light curve” of Tabby’s Star – named after the lead author of the study that first detailed the phenomena (Tabetha S. Boyajian) – was particularly pronounced and unusual.

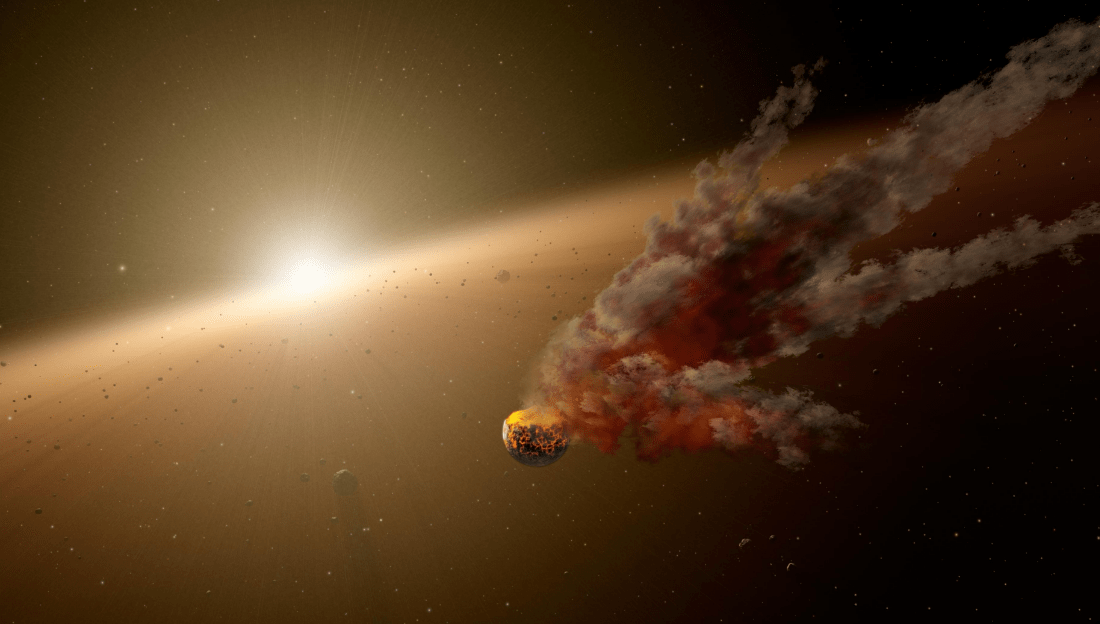

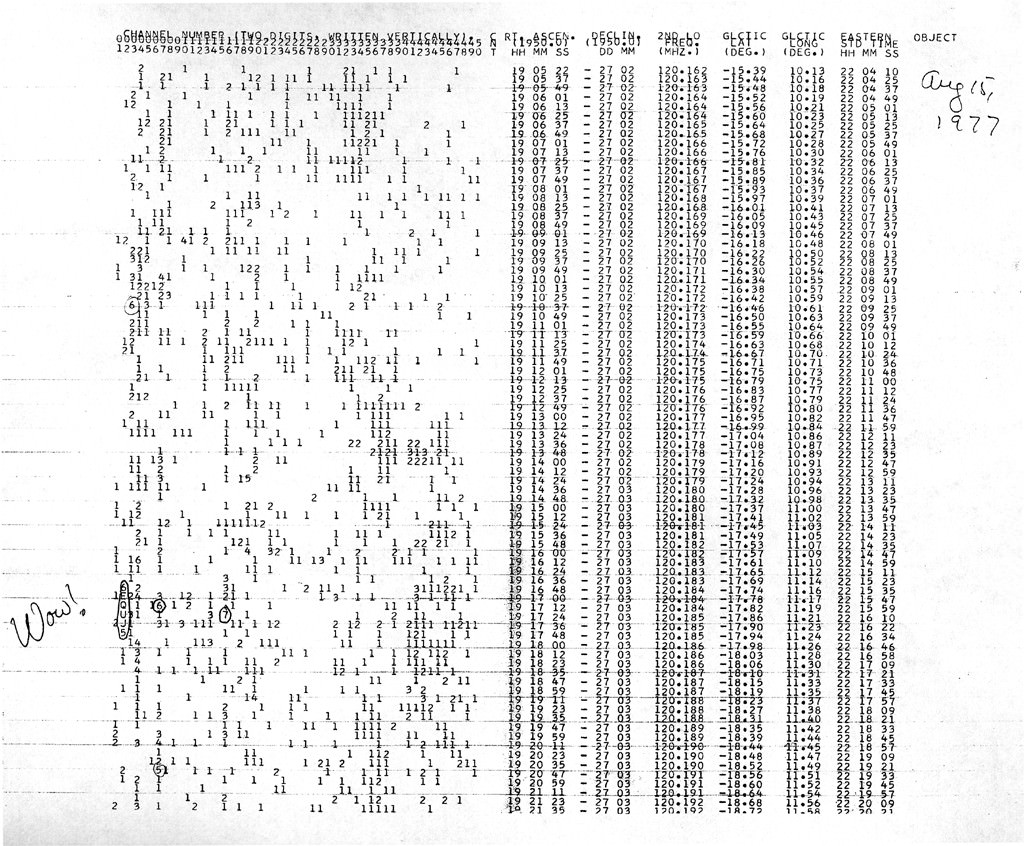

According to the study, the star would experience a ~20% dip in brightness, which would last for between 5 and 80 days. This was not consistent with a transitting planet, and Boyajian and her colleagues hypothesized that it was due to a swarm of cold, dusty comet fragments in a highly eccentric orbit accounted for the dimming.

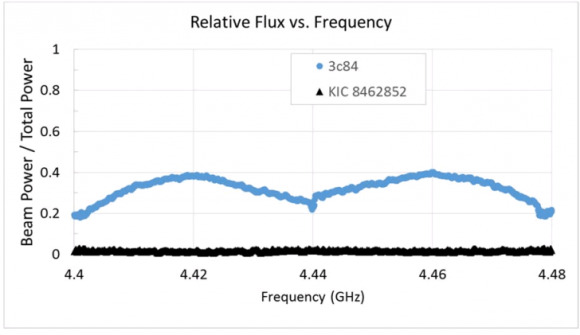

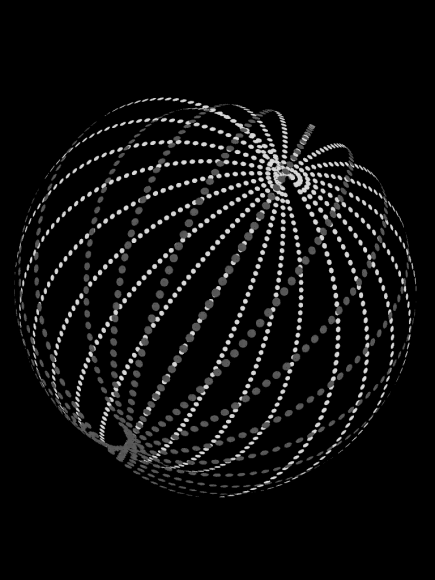

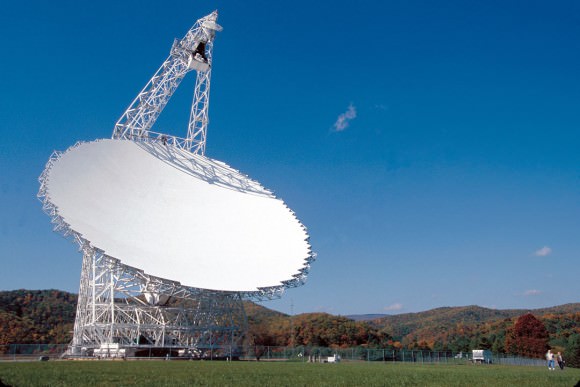

However, others speculated that it could be the result of an alien megastructure known as Dyson Sphere (or Swarm), a series of structures that encompass a star in whole or in part. However, the SETI Institute quickly weighed in and indicated that radio reconnaissance of KIC 8462852 found no evidence of technology-related radio signals from the star.

Other suggestions were made as well, but as Dr. Simon of the Carnegie Institute of Science explained via email, they fell short. “Because the brief dimming events identified by Boyajian et al. were unprecedented, they sparked a wide range of ideas to explain them,” he said. “So far, none of the proposals have been very compelling – in general, they can explain some of the behavior of KIC 8462852, but not all of it.”

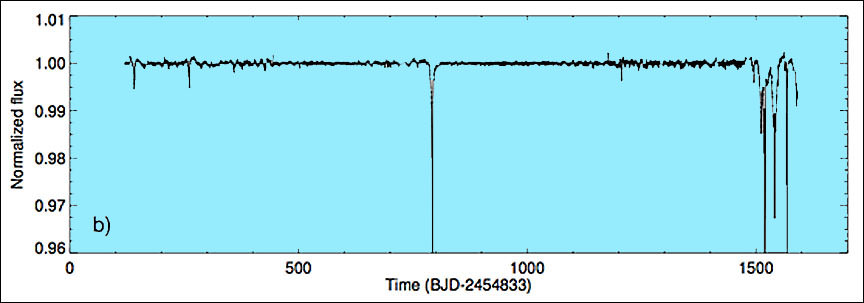

To put the observations made last Fall into a larger context, Montet and Simon decided to examine the full-frame photometeric images of KIC 8462852 obtained by Kepler over the last four years. What they found was that the total brightness of the star had been diminishing quite astonishingly during that time, a fact which only deepens the mystery of the star’s light curve.

As Dr. Montet told Universe Today via email:

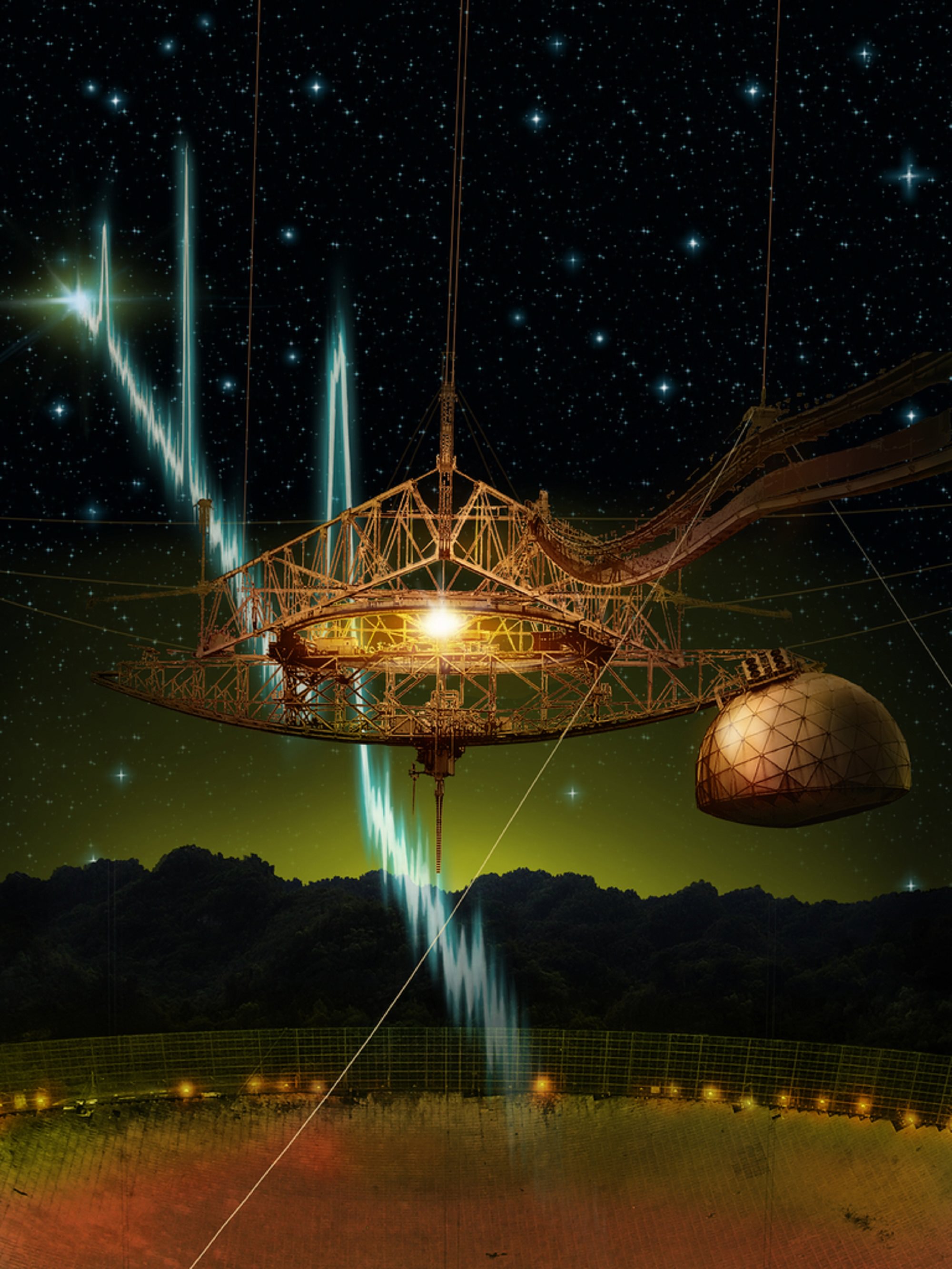

“Every 30 minutes, Kepler measures the brightness of 160,000 stars in its field of view (100 square degrees, or approximately as big as your hand at arm’s length). The Kepler data processing pipeline intentionally removes long-term trends, because they are hard to separate from instrumental effects and they make the search for planets harder. Once a month though, they download the full frame, so the brightness of every object in the field can be measured. From this data, we can separate the instrumental effects from astrophysical effects by seeing how the brightness of any particular star changes relative to all its neighboring stars.”

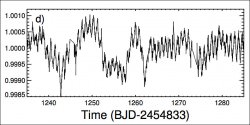

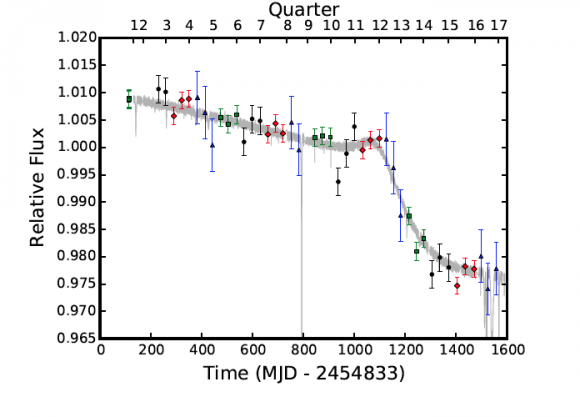

Specifically, they found that over the course of the first 1000 days of observation, the star experienced a relatively consistent drop in brightness of 0.341% ± 0.041%, which worked out to a total dimming of 0.9%. However, during the next 200 days, the star dimmed much more rapidly, with its total stellar flux dropping by more than 2%.

For the final 200 days, the star’s magnitude once again consistent and similar to what it was during the first 1000 – roughly equivalent to 0.341%. What is impressive about this is the highly anomalous nature of it, and how it only makes the star seem stranger. As Simon put it:

“Our results show that over the four years KIC 8462852 was observed by Kepler, it steadily dimmed. For the first 2.7 years of the Kepler mission the star faded by about 0.9%. Its brightness then decreased much faster for the next six months, declining by almost 2.5% more, for a total brightness change of around 3%. We haven’t yet found any other Kepler stars that faded by that much over the four-year mission, or that decreased by 2.5% in six months.”

Of the over 150,000 stars monitored by the Kepler mission, Tabby’s Starr is the only one known to exhibit this type of behavior. In addition, Monetet and Cahill compared the results they obtained to data from 193 nearby stars that had been observed by Kepler, as well as data obtained on 355 stars with similar stellar parameters.

From this rather large sampling, they found that a 0.6% change in luminosity over a four year period – which worked out to about 0.341% per year – was quite common. But none ever experienced the rapid decline of more than 2% that KIC 8462852 experienced during that 200 days interval, or the cumulative fading of 3% that it experienced overall.

Montet and Cahill looked for possible explanations, considering whether the rapid decline could be caused by a cloud of transiting circumstellar material. But whereas some phenomena can explain the long-term trend, and other the short-term trend, no one explanation can account for it all. As Montet explained:

“We propose in our paper that a cloud of gas and dust from the remnants of a planetesimal after a collision in the outer solar system of this star could explain the 2.5% dip of the star (as it passes along our line of sight). Additionally, if some clumps of matter from this collision were collided into high-eccentricity comet-like orbits, they could explain the flickering from Boyajian et al., but this model doesn’t do a nice job of explaining the long-term dimming. Other researchers are working to develop different models to explain what we see, but they’re still working on these models and haven’t submitted them for publication yet. Broadly speaking, all three effects we observe cannot be explained by any known stellar phenomenon, so it’s almost certainly the result of some material along our line of sight passing between us and the star. We just have to figure out what!”

So the question remains, what accounts for this strange dimming effect around this star? Is there yet some singular stellar phenomena that could account for it all? Or is this just the result of good timing, with astronomers being fortunate enough to see a combination of a things at work in the same period? Hard to say, and the only way we will know for sure is to keep our eye on this strangely dimming star.

And in the meantime, will the alien enthusiasts not see this as a possible resolution to the Fermi Paradox? Most likely!

Further Reading: arXiv