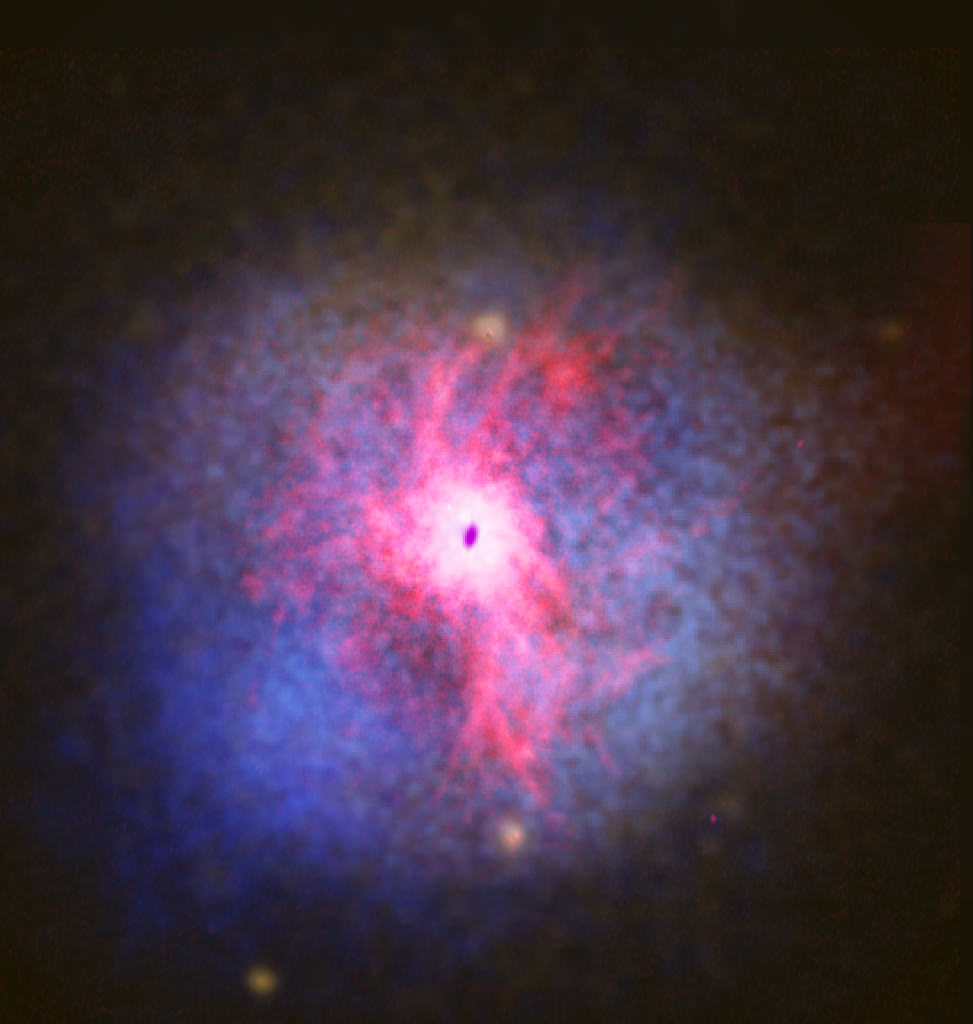

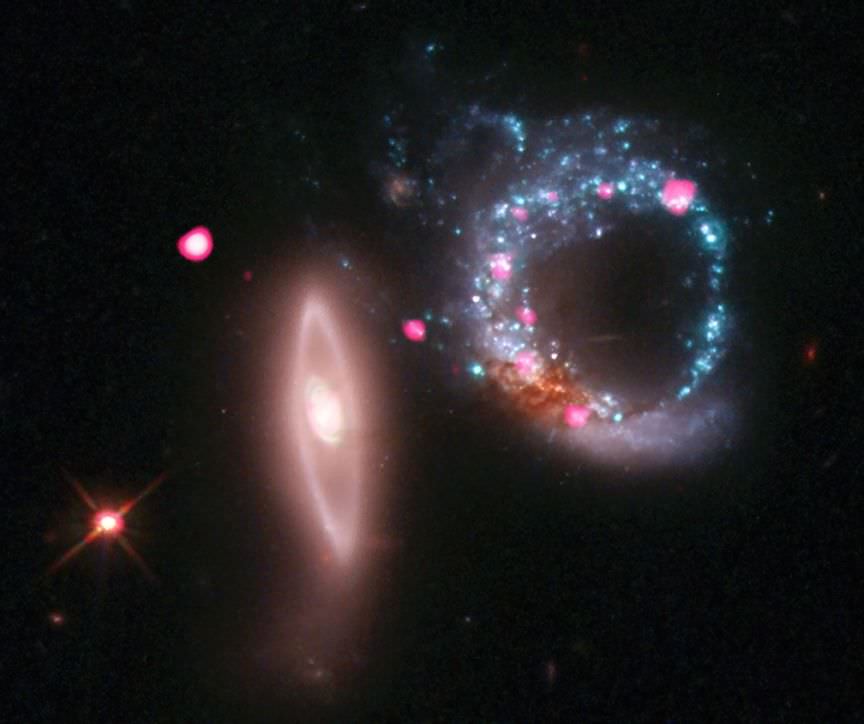

The tangled remains of vast cosmic collisions can be seen across the universe, such as the distant Whirlpool Galaxy’s past close encounter with a nearby galaxy, which resulted in the staggering beauty we see today.

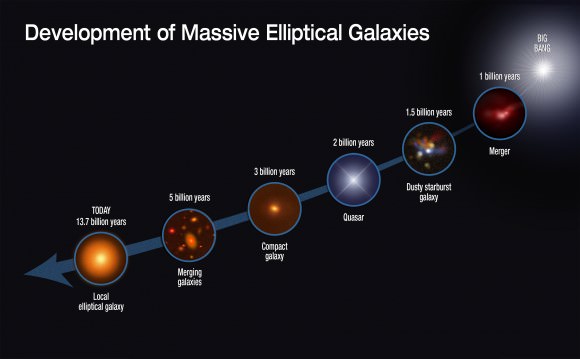

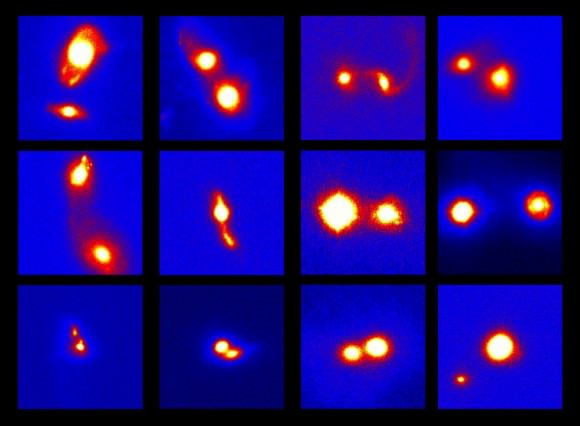

Such colossal collisions between galaxies appear to be common. It’s likely giant galaxies, such as our own, originated long ago after smaller dwarf galaxies crashed together. Unfortunately, Hubble has yet to peer into the early Universe and catch two dwarf galaxies merging by chance. And they’re extremely rare to catch in the present nearby universe.

But for the first time, astronomers have uncovered evidence of a similar collision much closer to home.

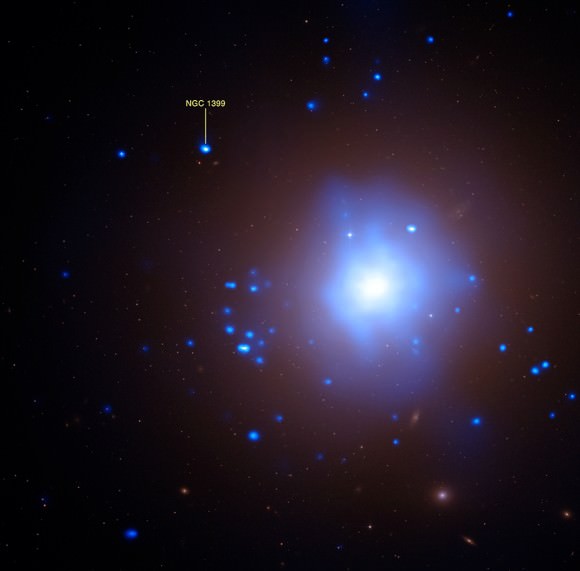

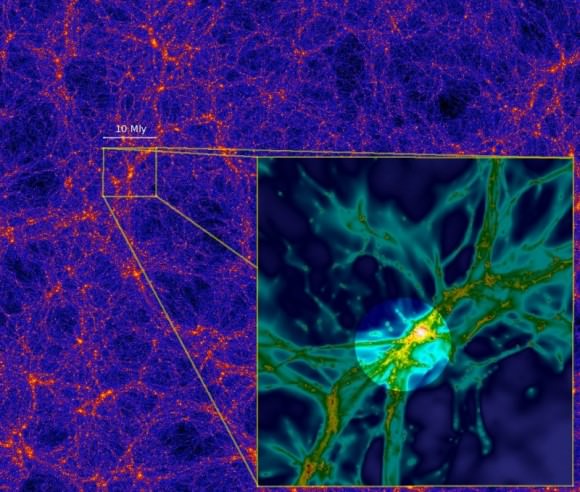

The Milky Way is part of a large cosmic neighborhood. A collection of more than 35 galaxies compose the Local Group. While the largest and heavier members are the Milky Way and the Andromeda galaxy, there are many smaller satellite galaxies orbiting the two. Anyone who has looked at the southern sky should be familiar with the Large and Small Magellanic Clouds: two satellite galaxies of the Milky Way less than 200,000 light years away.

Andromeda has over 20 satellite galaxies circling its nearly a trillion stars. A team of European astronomers has analyzed measurements of the stars in the dwarf galaxy Andromeda II — the second largest dwarf galaxy in the Local Group — and made a surprising discovery: an odd stream of stars that simply doesn’t belong.

The team led by Dr. Nicola C. Amorisco from the Dark Cosmology Centre at the Niels Bohr Institute in Copenhagen used the Deep Imaging Multi-Object (DEIMOS) spectrograph onboard the Keck II telescope in Hawaii in order to measure the velocities of more than 700 stars in the Andromeda II dwarf galaxy.

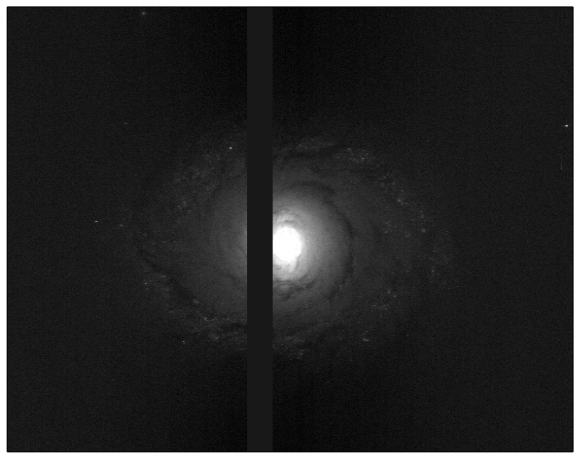

Stars in a large spiral galaxy will move, on average, with the rotation of the galaxy. On one side of the galaxy’s spinning disk, the stars will be moving away from the Earth, and their light waves will be stretched to redder wavelengths. On the opposite side, the stars will be moving toward the Earth, and their light waves will be compressed to bluer wavelengths.

But the stars in dwarf galaxies don’t exhibit such a pattern. Instead they move around entirely at random.

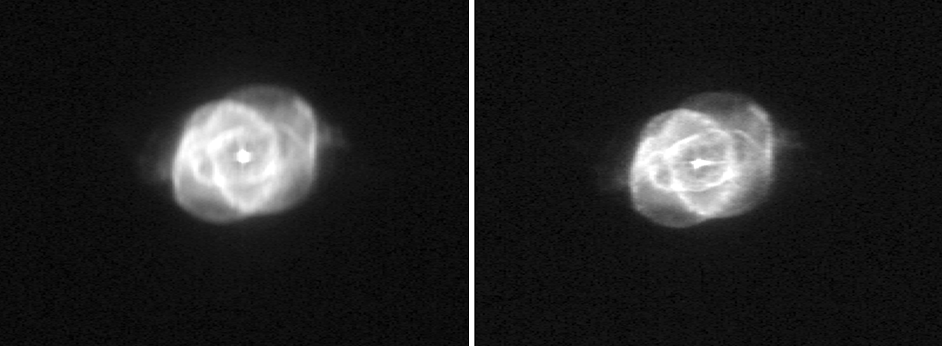

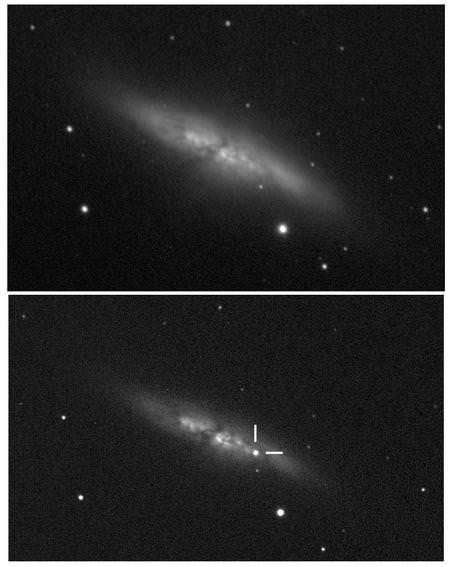

Amorisco and colleagues, however, found a rather different case present in Andromeda II. They observed a stream of stars — roughly 16,000 light years in length and 980 light years in thickness — that didn’t exhibit random motions at all. They orbit the center of the galaxy in a very coherent fashion.

But it gets better: the stars in this stream are also much colder than the stars outside the stream. In astronomy this is the equivalent of saying that the stars in this stream are much older. Amorisco’s team now believes they once belonged to a different galaxy entirely and remain only as a remnant of the past collision, which likely occurred over 3 billion years ago.

Streams of stars often result from collisions. As two galaxies begin to interact, the stars nearest the approaching galaxy feel a much stronger gravitational pull than the stars further away. Eventually the gravitational pull on the closer side of the galaxy will pull the stars from their initial galaxy, creating a stream of stars, dust and gas.

This is the smallest known example of two galaxies merging. The finding adds further evidence that mergers between dwarf galaxies plays a fundamental role in creating the large and beautiful galaxies we see today.

The paper has been published in Nature and is available for download here.