For decades astronomers have puzzled over the many details concerning the formation of the Milky Way Galaxy. Now a group of scientists headed by Ivan Minchev from the Leibniz Institute for Astrophysics Potsdam (AIP) have managed to retrace our galaxy’s formative periods with more detail than ever before. This newly published information has been gathered through careful observation of stars located near the Sun and points to a rather “moving” history.

To achieve these latest results, astronomers observed stars perpendicular to the galactic disc and their vertical motion. Just to shake things up, these stars also had their ages considered. Because it is nearly impossible to directly determine a star’s true age, they rattled the cage of chemical composition. Stars which show an increase in the ratio of magnesium to iron ([Mg/Fe]) appear to have a greater age. These determinations of stars close to the Sun were made with highly accurate information gathered by the RAdial Velocity Experiment (RAVE). According to previous findings, “the older a star is, the faster it moves up and down through the disc”. This no longer seemed to be true. Apparently the rules were broken by stars with the highest magnesium-to-iron ratios. Despite what astronomers thought would happen, they observed these particular stars slowing their roll… their vertical speed decreasing dramatically.

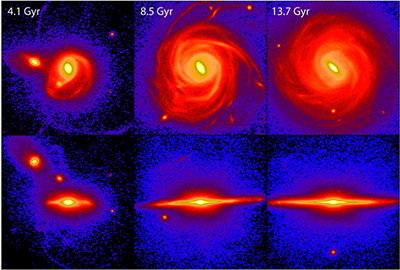

So what’s going on here? To help figure out these curious findings, the researchers turned to computer modeling. By running a simulation of the Milky Way’s evolutionary patterns, they were able to discern the origin of these older, slower stars. According to the simulation, they came to the conclusion that small galactic collisions might be responsible for the results they had directly observed.

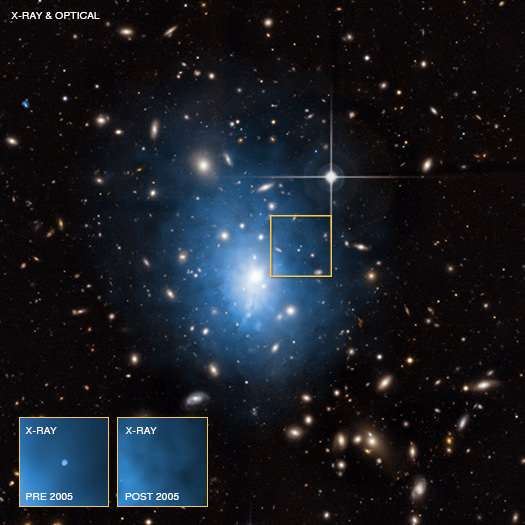

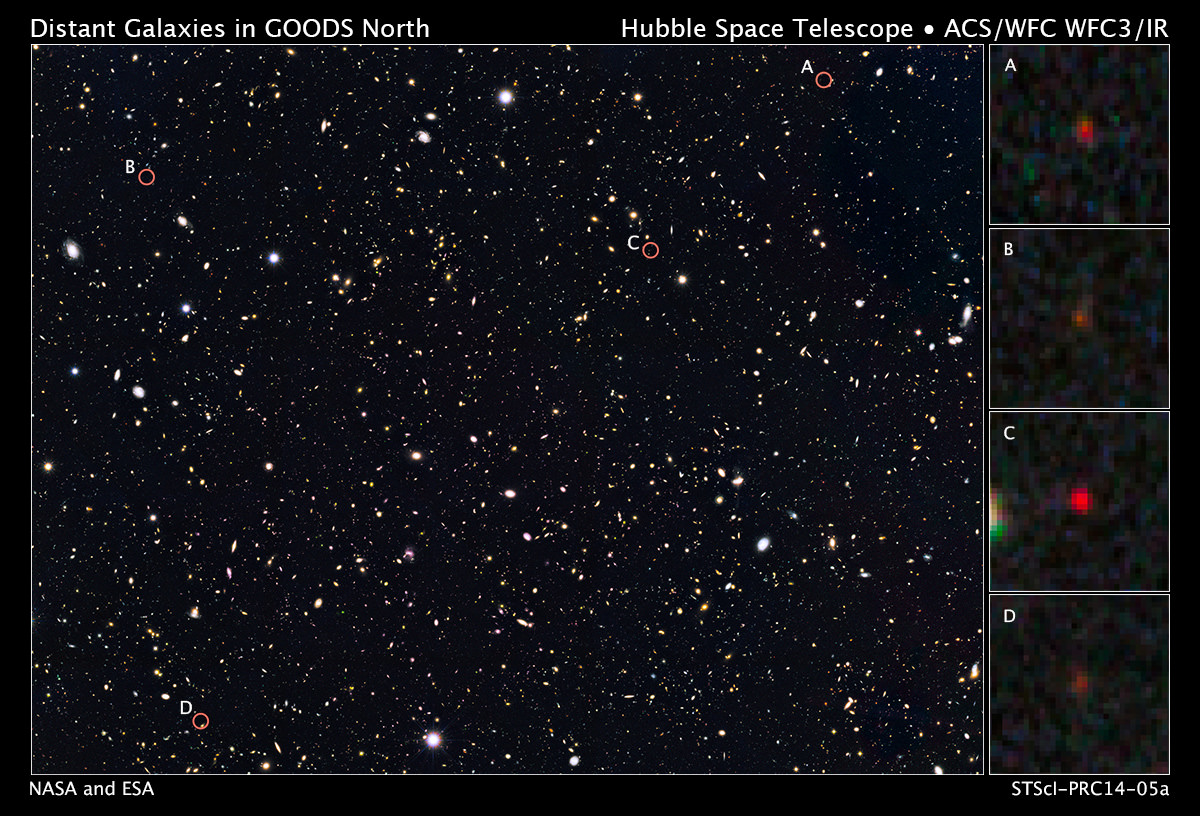

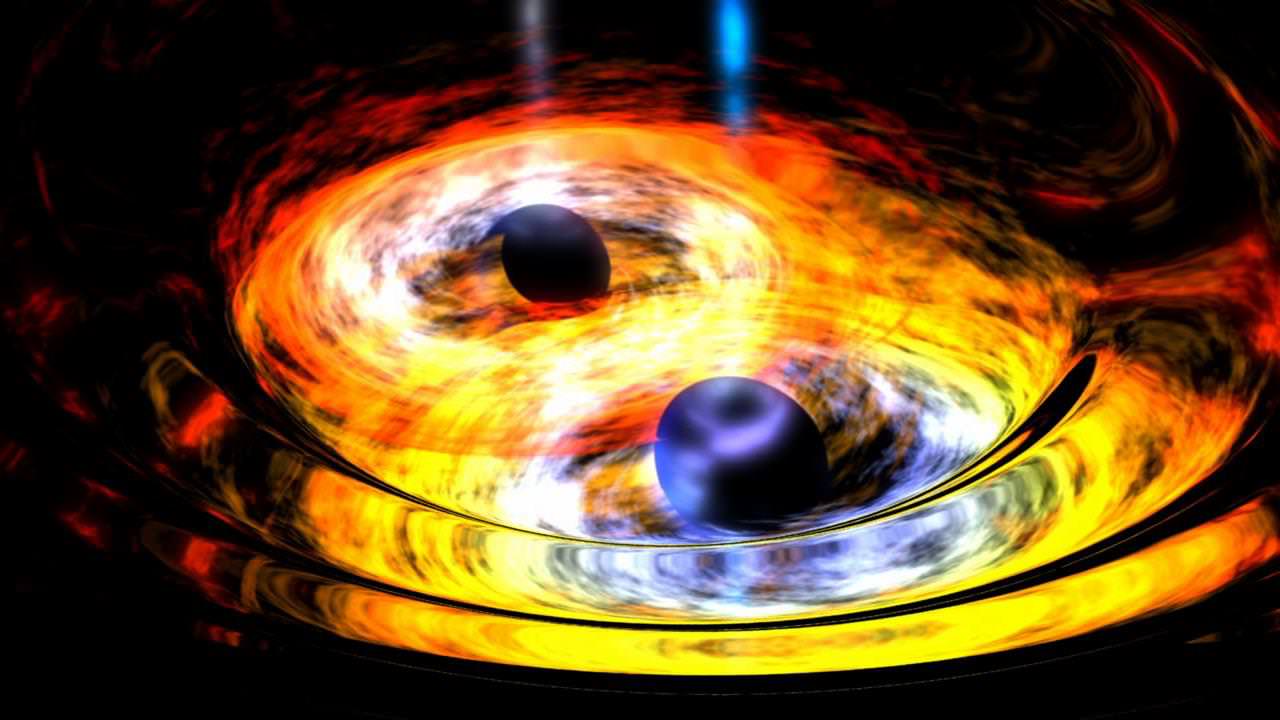

Smashing into, or combining with, a smaller galaxy isn’t new to the Milky Way. It is widely accepted that our galaxy has been the receptor of galactic collisions many times during its course of history. Despite what might appear to be a very violent event, these incidents aren’t very good at shaking up the massive regions near the galactic center. However, they stir things up in the spiral arms! Here star formation is triggered and these stars move away from the core towards our galaxy’s outer edge – and near our Sun.

In a process known as “radial migration”, older stars, ones with high values of magnesium-to-iron ratio, are pushed outward and display low up-and-down velocities. Is this why the elderly, near-by stars have diminished vertical velocities? Were they forced from the galactic center by virtue of a collision event? Astronomers speculate this to be the best answer. By comparison, the differences in speed between stars born near the Sun and those forced away shows just how massive and how many merging galaxies once shook up the Milky Way.

Says AIP scientist Ivan Minchev: “Our results will enable us to trace the history of our home galaxy more accurately than ever before. By looking at the chemical composition of stars around us, and how fast they move, we can deduce the properties of satellite galaxies interacting with the Milky Way throughout its lifetime. This can lead to an improved understanding of how the Milky Way may have evolved into the galaxy we see today.”

Original Story Source: Leibniz Institute for Astrophysics Potsdam News Release. For further reading: A new stellar chemo-kinematic relation reveals the merger history of the Milky Way.