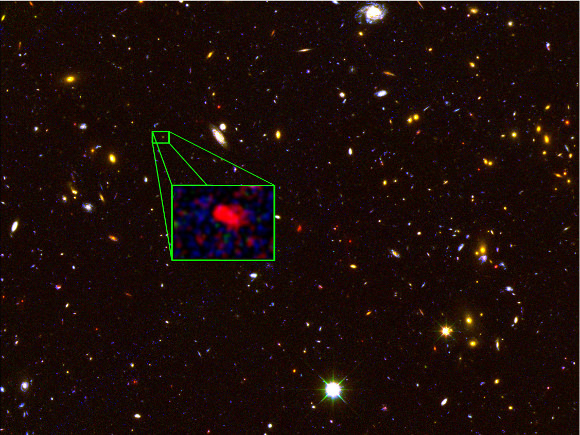

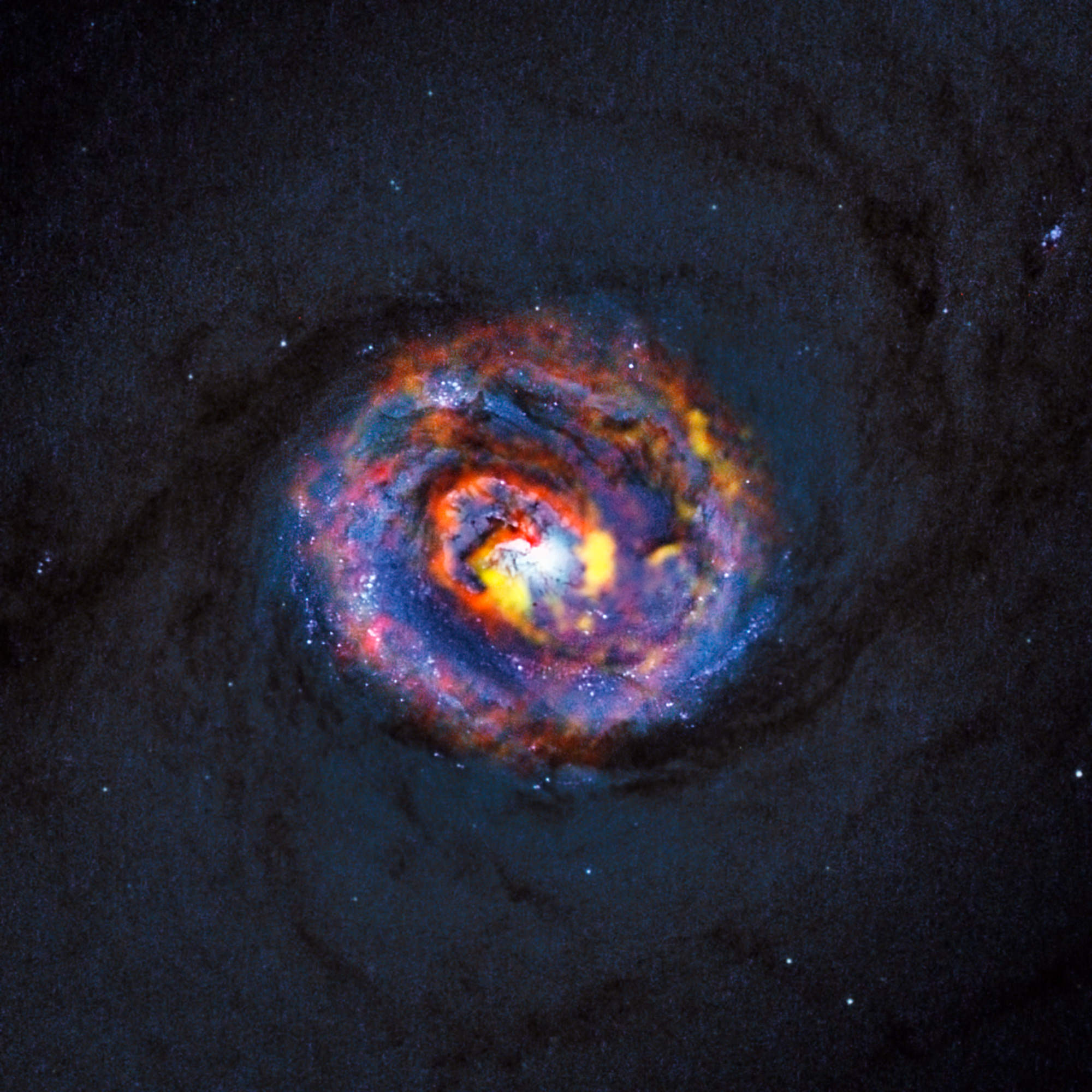

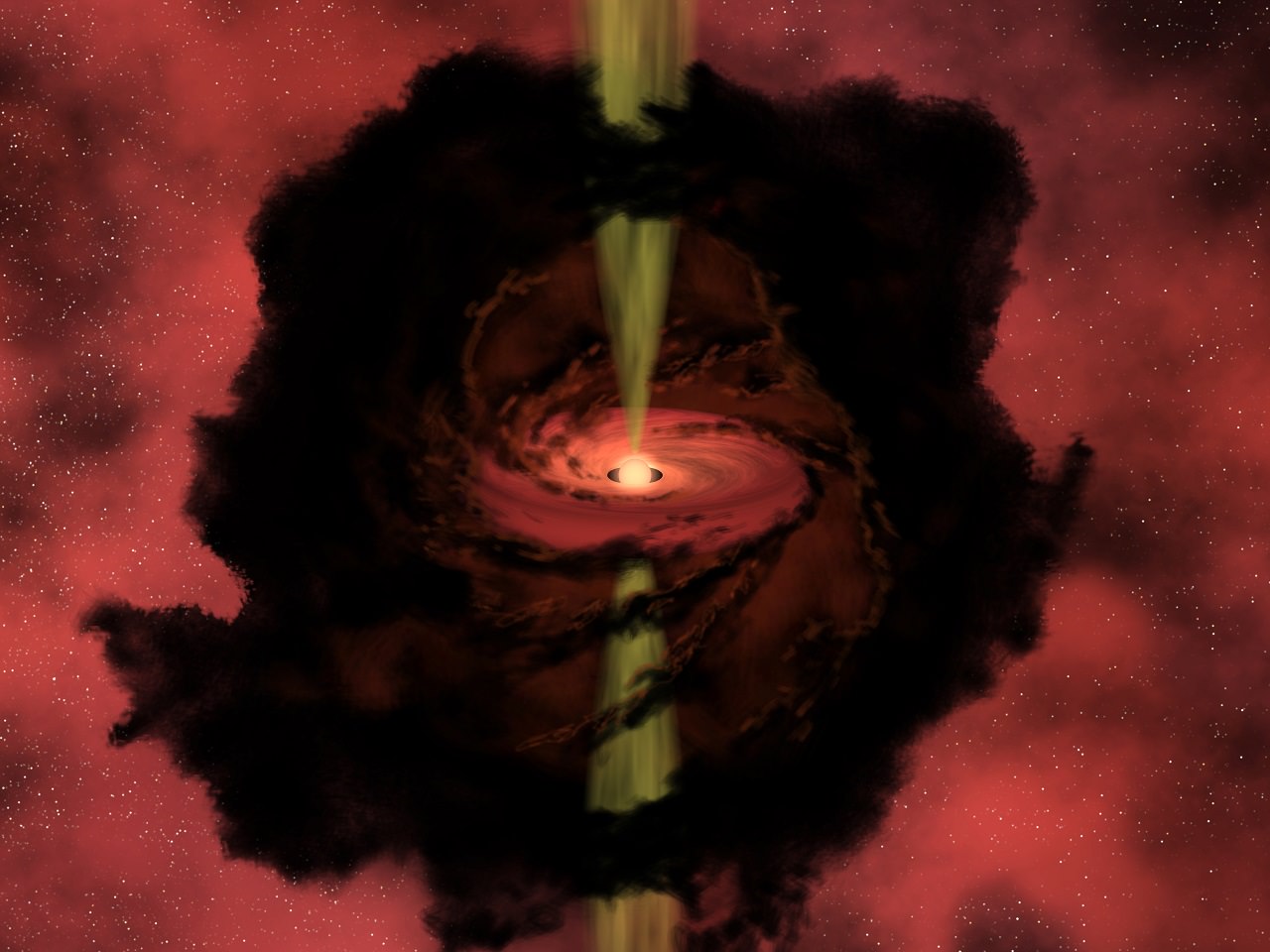

Nobody likes a sloppy COSMOS (Cosmological Evolution Survey) and astronomers utilizing the Fiber-Multi-Object Spectrograph (FMOS) mounted on the Subaru Telescope have put order into chaos through their studies. The survey has found that some nine billion years ago galaxies were capable of producing new stars in a fashion as orderly as game of checkers. Despite their young cosmological age, the galaxies show signs containing high amounts of dust enriched by heavier elements – a mature state.

“These findings center on a major question: What was the universe like when it was maximally forming its stars?” says John Silverman, the principal investigator of the FMOS-COSMOS project at the Kavli Institute for the Physics and Mathematics of the Universe (Kavli IPMU).

These “universal” questions are just what the COSMOS team seeks to answer. Their research goals are to enlighten the scales of cosmic time in relationship with the environment, formation and evolution of massive galactic structures. When studying individual galaxies, they may be able to tell if their rate of growth can be attributed to large-scale environments. Information of this type can clarify what factors the early Universe structure may have contributed to the current form of local galaxies. One of the data sets the team is focusing on is using the FMOS on the Subaru Telescope to chart out the distribution of more than a thousand galaxies which formed over nine billion years ago – a time when the Universe was hitting its star-formation peak.

“One key to generating fruitful results is collaboration between COSMOS researchers to maximize optimal use of FMOS.” Silverman continues, “In this project, researchers from Kavli IPMU in Japan and the Institute for Astronomy at the University of Hawaii (principal investigator: David Sanders) formed an effective collaboration to implement their goal.” The observations spanned 10 clear nights starting in March 2012.

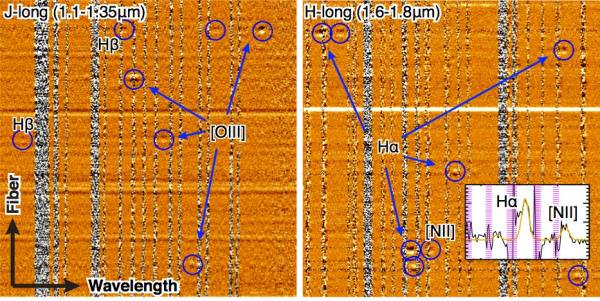

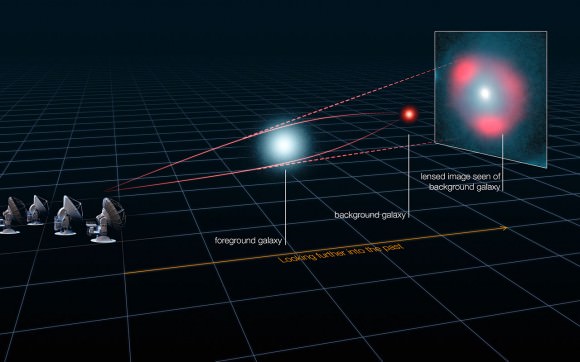

Why choose spectroscopy? This advanced fiber optics technology speaks for itself, collecting light over an area of sky equal in size to that of the Moon. The FMOS focuses on the near-infrared, filtering out unwanted emissions caused by warm temperatures and can acquire spectra from 400 galaxies simultaneously with a wide field of coverage of 30 arc minutes at prime-focus. By employing such a wide field of view, astronomers can squeeze in a wide range of objects in their local environments. This enables researchers to maximize information on star-forming regions, cluster formation, and cosmology.

As David Sanders, the principal investigator of the FMOS-COSMOS project at IfA, puts it, “FMOS has clearly revolutionized our ability to study how galaxies form and evolve across cosmic time. It is currently the most powerful instrument we have to study the large numbers of objects needed to understand galaxies of all sizes, shapes and masses — from the largest ellipticals to the smallest dwarfs. We are extremely fortunate that the Kavli IPMU-IfA collaboration is giving us this unique opportunity to study the distant universe in such exquisite detail.”

FMOS will soon be famous by revealing its true potential. It has been collecting copious amounts of data in a high spectral resolution mode and at a very successful rate. So far it has accomplished nearly half of its goal – to examine over a thousand galaxies with redshifts to map the large-scale structure. The current survey consists of mapping an area of sky which spans a square degree in high-resolution mode and future plans for FMOS will involve enlarging the area. This expanded coverage will complement other instruments on alternative telescopes which have a wider spectral imaging system or a higher resolution which is limited to a smaller area. These combined findings may one day result in showing us some of the very first structures that eventually evolved into the massive galaxy clusters we see today!

Original Story Source: Kavli Institute for the Physics and Mathematics of the Universe News Release.