Sometimes, you just have to say “Wow!”

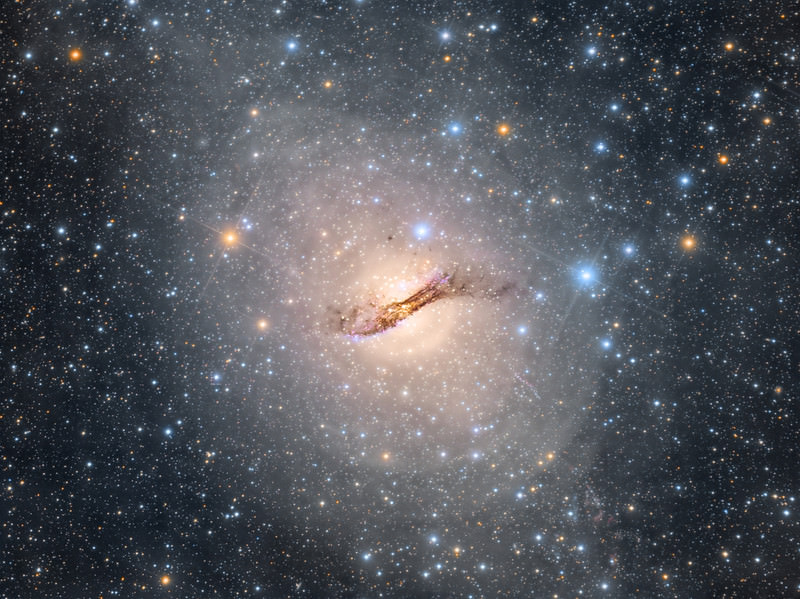

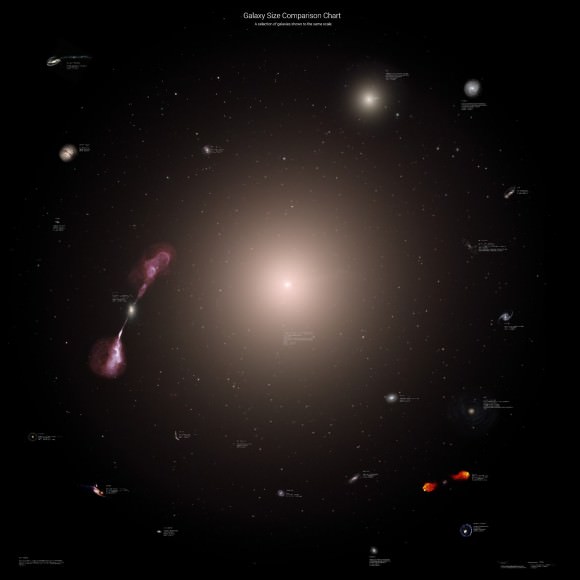

The view you’re looking at above is of Centaurus A (NGC 5128), a galaxy about 10-16 million light years distant in the southern hemisphere sky. It’s a favorite of astrophotographers and professional observatories alike.

But what makes this image so special is that it was taken by an amateur astrophotographer.

To construct this amazing image, New Zealand-based astrophotographer Rolf Wahl Olsen exposed the field of view for 120 hours over 43 nights spanning February to May of this year.

Rolf recently shared his motivation to construct this image;

“Over the past few months I have been on a mission to achieve a long time dream of mine: taking a deep sky image with more than 100 hours of exposure.”

Rolf also noted that the stars in the frame are visible down to magnitude +25.45, which “appears to go deeper than the recent ESO release” and believes that it may well be “the deepest view ever obtained of Centaurus A,” As well as “the deepest image ever taken with amateur equipment.”

Not only is the beauty and splendor of the galaxy revealed in this stunning mosaic, but you can see the variations in the populations of stars in the massive regions undergoing an outburst of star formation.

One can also see the numerous globular clusters flocking around the galaxy, as well as the optical counterparts to the radio lobes and the faint trace of the relativistic jets. The extended halo of the outer shell of stars is also visible, along with numerous foreground stars visible in the star rich region of Centaurus.

Finally, we see the dusty lane bisecting the core of this massive galaxy as seen from our Earthly vantage point.

To our knowledge, many of these features have never been captured visually by backyard observers before, much less imaged. Congrats to Rolf Wahl Olsen on a spectacular capture and sharing his view of the universe with us!

Read more on the Centaurus A deep field on Google+.

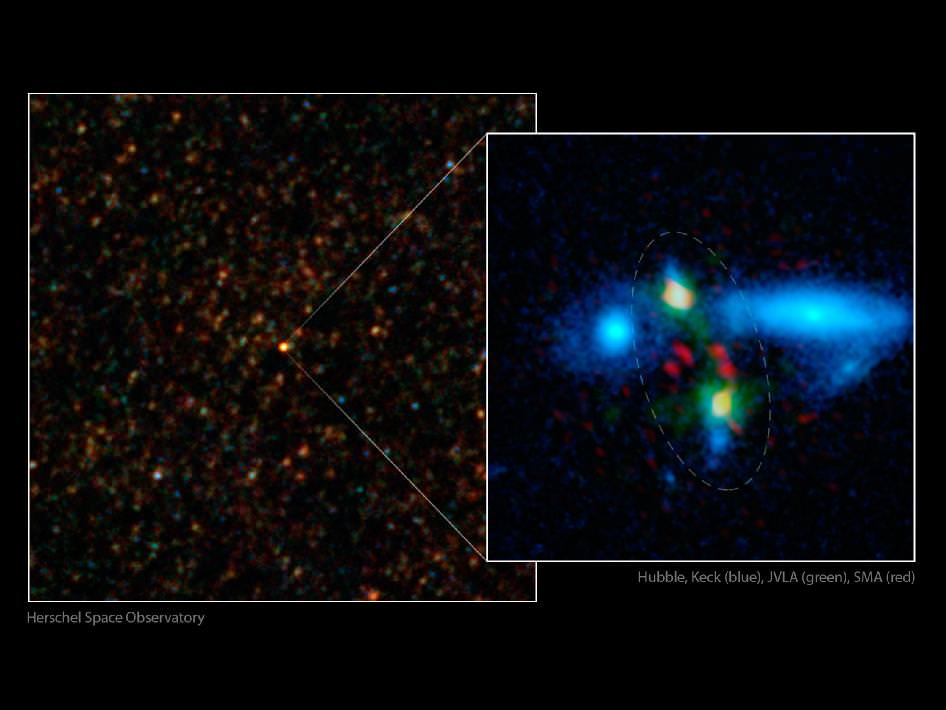

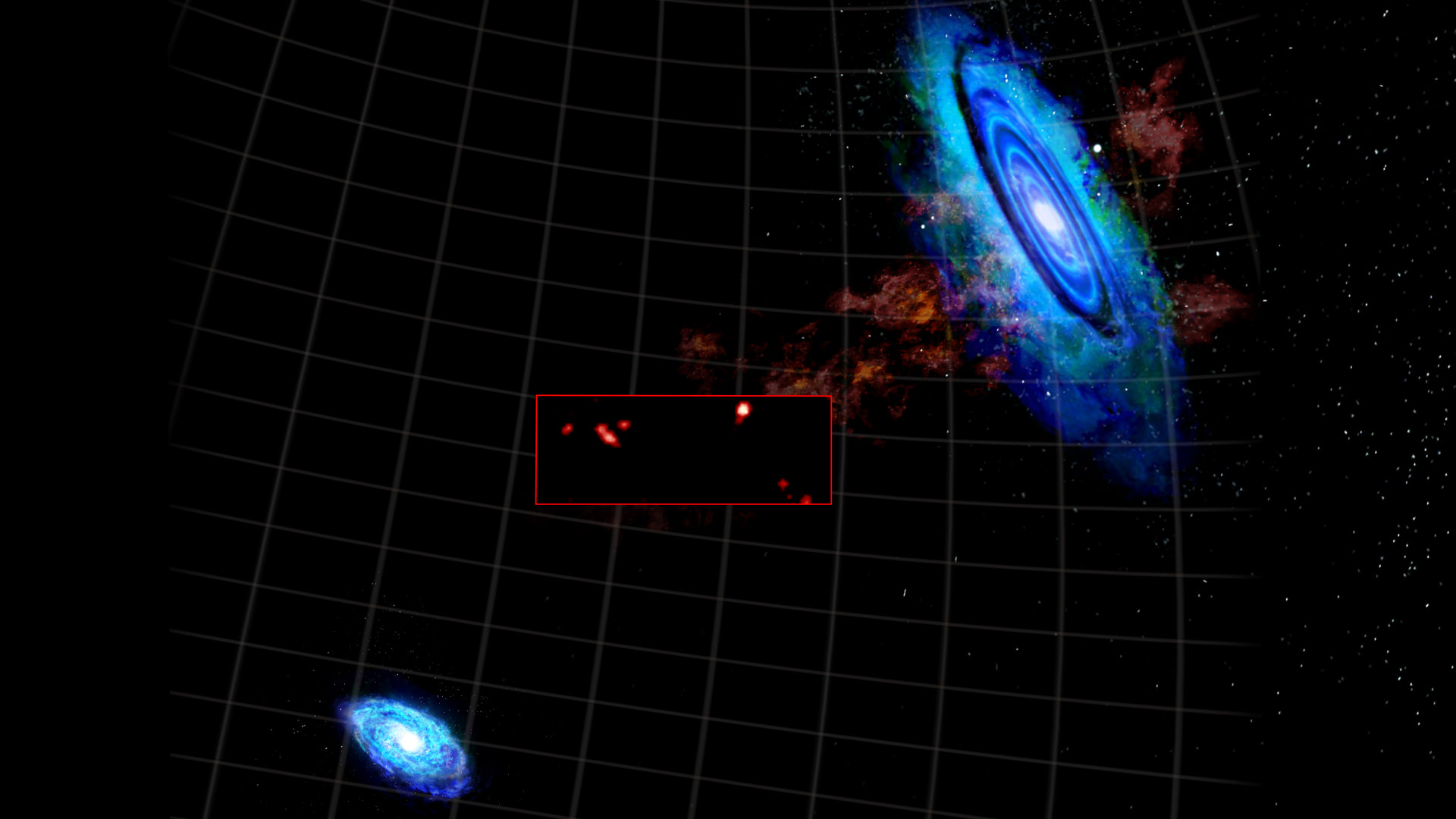

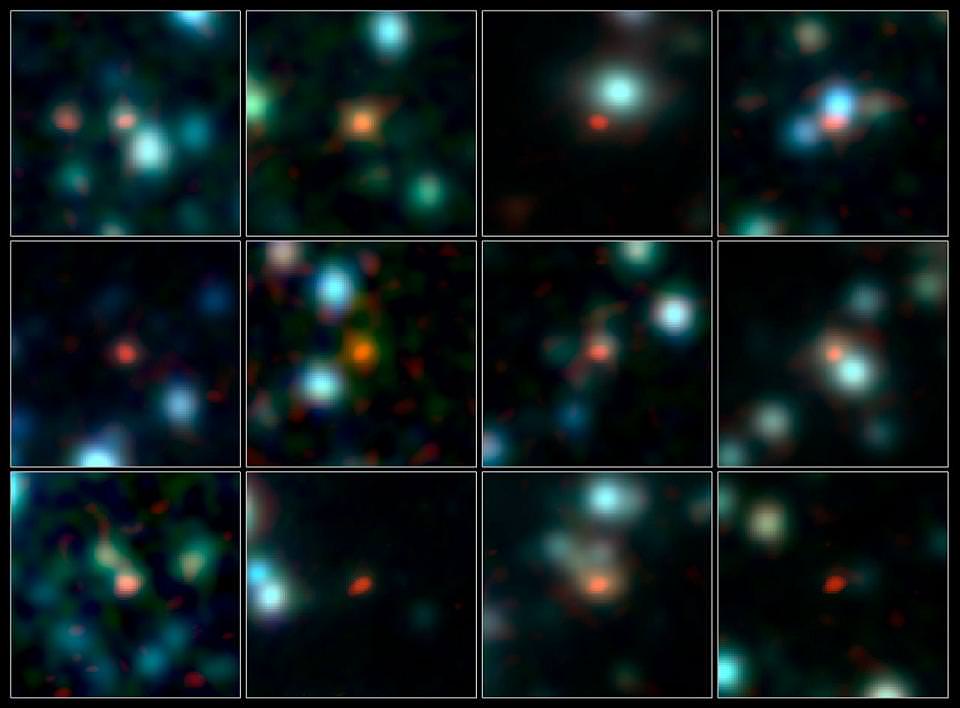

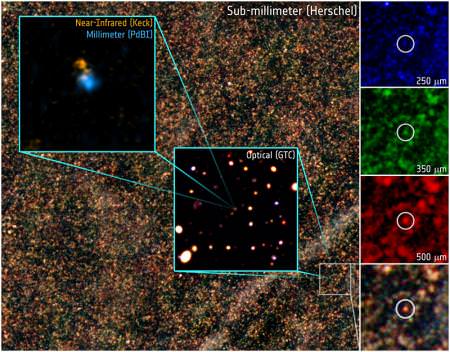

-Check out the comparison images of the Centaurus A deep field showing the relativistic jet (!) background galaxies and clusters.

-Explore more of Rolf’s outstanding work at his website.