[/caption]

Greeting, fellow SkyWatchers! It’s gonna’ be a great week! We start off with a partial lunar eclipse of the Strawberry Moon, head into the historic Venus Transit, study some Herschel objects, catch both the Scorpid and Arietid Meteor Showers, practice some binocular astronomy and even take on some challenge objects! How awesome is that? Whenever you’re ready, just follow me into the back yard…

Monday, June 4 – Tonight the Moon is full. Often referred to as the Full Strawberry Moon, this name was a constant to every Algonquin tribe in North America. But, our friends in Europe referred to it as the Rose Moon. The North American version came about because the short season for harvesting strawberries comes each year during the month of June – so the full Moon that occurs during that month was named for this tasty red fruit!

This evening as the Sun sets and the Moon rises opposite of it, take advantage of some quiet time and really stop to look at the eastern horizon. If you are lucky enough to have clear skies, you will see the Earth’s shadow rising – like a dark, sometimes blue band – that stretches around 180 degrees of horizon. Look just above it for a Rayleigh scattering effect known as the “Belt of Venus”. This beautiful pinkish glow is caused by the backscattering of sunlight and is often referred to as the anti-twilight arch. As the Sun continues to set, this boundary between our shadow and the arch rises higher in the sky and gently blends with the coming night. What you are seeing is the shadow of the Earth’s translucent atmosphere, casting a shadow back upon itself. This happens every night! Pretty cool, huh?

For some of us, it’s eclipse time! According to NASA’s Fred Espenak, most of the Americas will experience moonset before the partial lunar eclipse ends while eastern Asia will miss the beginning of the eclipse because it occurs before moonrise. The Moon’s contact times with Earth’s shadows are: Penumbral Eclipse Begins: 08:48:09 UT, Partial Eclipse Begins: 09:59:53 UT, Greatest Eclipse: 11:03:13 UT, Partial Eclipse Ends: 12:06:30 UT, Penumbral Eclipse Ends: 13:18:17. At the instant of greatest eclipse the umbral eclipse magnitude will reach 0.3705. At that time the Moon will be at the zenith for observers in the South Pacific. In spite of the fact that just a third of the Moon enters the umbral shadow (the Moon’s southern limb dips 12.3 arc-minutes into the umbra) the partial phase still lasts over 2 hours. Be sure to visit the resource pages for a visibility map and links to precise times and locations!

Tuesday, June 5 – Heads up for all observers! Today’s universal date marks an historic event – Venus will transit the Sun! This event will cross international date lines, so be sure to know ahead of time when and where to watch. North America will be able to see the start of the transit, while South Asia, the Middle East, and most of Europe will catch the end of it. For some great information on when, where and how to watch, visit www.transitofvenus.org. If you’re clouded out, there’s plenty of resources on-line to view this rare event. One that promises to have plenty of extra bandwidth to serve visitors is Astronomy Live. Be there!!

For all you Stargazers, keep watch for the Scorpid meteor shower. Its radiant will be near the constellation of Ophiuchus, and the average fall rate will be about 20 per hour with some fireballs.

While you’re out, take the time to check out Alpha Herculis -Ras Algethi. You will find it not only to be an interesting variable, but a colorful double as well. The primary star is one of the largest known red giants and at about 430 light years away, it is also one of the coolest. Its 5.4 magnitude greenish companion star is easily separated in even small scopes – but even it is a binary! This entire star system is enclosed in an expanding gaseous shell that originates from the evolving red giant. Enjoy it tonight.

Wednesday, June 6 – So far we’ve studied many Herschel objects in disguise as Messier catalog items – but we haven’t really focused on some mighty fine galaxies that are within the power of the intermediate to large telescope. Tonight let’s take a serious skywalk as we head to 6 Comae and drop two degrees south.

At magnitude 10.9, Herschel catalog object H I.35 is also known by its New General Catalog number of 4216 (Right Ascension: 12 : 15.9 – Declination: +13 : 09). This splendid edge-on galaxy has a bright nucleus and will walk right out in larger telescopes with no aversion required. But, the most fascinating part about studying anything in the Virgo cluster is about to be revealed.

While studying structure in NGC 4216, averted vision picks up magnitude 12 NGC 4206 (Right Ascension:12 : 15.3 – Declination: +13 : 02) to the south. This is also a Herschel object – H II.135. While it is smaller and fainter, the nucleus will be the first thing to catch your attention – and then you’ll notice it is also an edge-on galaxy! As if this weren’t distracting enough, while re-centering NGC 4216, sometimes the movement is just enough to allow the viewer to catch yet another edge-on galaxy to the north – NGC 4222 (Right Ascension: 12 : 16.4 – Declination: +13 : 19). At magnitude 14, you can only expect to be able to see it in larger scopes, but what a treat this trio is!

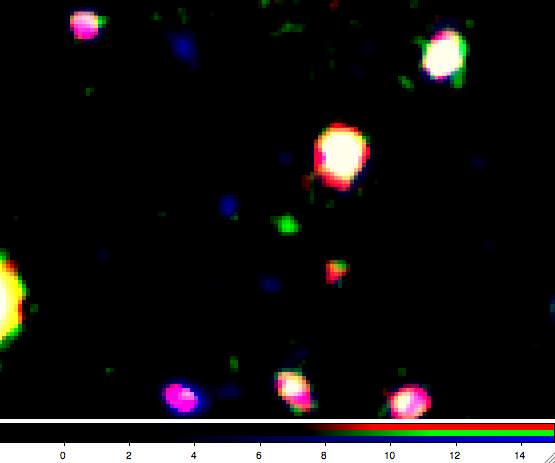

Is there a connection between certain types of galaxy structures within the Virgo cluster? Science certainly seems to think so. While low metallicity studies involving these galaxies are going on, research into evolution of galaxy clusters themselves continue to make new strides forward in our understanding of the universe. Capture them tonight!

Thursday, June 7 – If you’re up before dawn the next two days or out just after sunset, enjoy the peak of the June Arietid meteors – the year’s strongest daylight shower – with up to 30 visible per hour.

If you’d like to try your ear at radio astronomy with the offspring of sungrazing asteroid Icarus, tune an FM radio to the lowest frequency not receiving a clear signal. An outdoor antenna pointed at the zenith increases your chances, but even a car radio can pick up strong bursts! Simply turn up the static and listen. Those hums, whistles, beeps, bongs, and occasional snatches of signals are our own radio signals being reflected off the meteor’s ion trail!

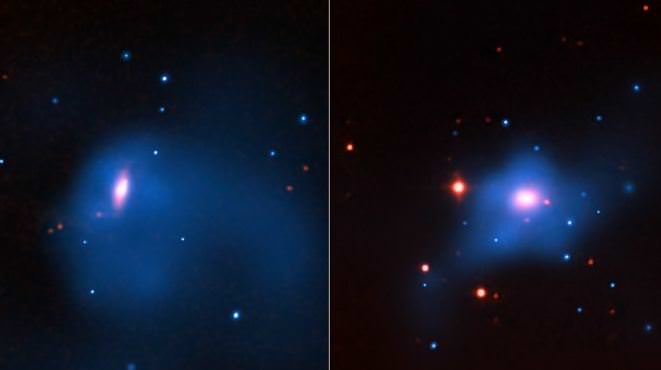

Tonight let’s study a radio-source galaxy so bright it can be seen in binoculars – 8.6 magnitude M87 (Right Ascension: 12 : 30.8 – Declination: +12 : 24), about two fingerwidths northwest of Rho Virginis. This giant elliptical was discovered by Charles Messier in 1781 and cataloged as M87. Spanning 120,000 light-years, it’s an incredibly luminous galaxy containing far more mass and stars than the Milky Way – gravitationally distorting its four dwarf satellites galaxies. M87 is known to contain in excess of several thousand globular clusters – up to 150,000 – and far more than our own 200.

In 1918, H. D. Curtis of Lick Observatory discovered something else – M87 has a jet of gaseous material extending from its core and pushing out several thousand light-years into space. This highly perturbed jet exhibits the same polarization as synchrotron radiation – a property of neutron stars. Containing a series of small knots and clouds as observed by Halton Arp at Palomar in 1977, he also discovered a second jet in 1966 erupting in the opposite direction. Thanks to these two properties, M87 made Arp’s “Catalog of Peculiar Galaxies” as number 152.

In 1954 Walter Baade and R. Minkowski identified M87 with radio source Virgo A, discovering a weaker halo in 1956. Its position over an x-ray cloud extending through the Virgo cluster make M87 a source of an incredible amount of x-rays. Because of its many strange properties, M87 remains a target of scientific investigation. The Hubble has shown a violent nucleus surrounded by a fast rotating accretion disc, whose gaseous make-up may be part of a huge system of interstellar matter. As of today, only one supernova event has been recorded – yet M87 remains one of the most active and highly prized study galaxies of all. Capture it tonight!

Friday, June 8 – Born on this date in 1625 was Giovanni Cassini – the most notable observer following Galileo. As head of the Paris Observatory for many years, he was the first to observe seasonal changes on Mars and measure its parallax (and so, its distance). This set the scale of the solar system for the first time. Cassini was the first to describe Jovian features, and studied the Galilean moons’ orbits. He also discovered four moons of Saturn, but he is best remembered for being the first to see the namesake division between the A and B rings.

Why not honor Cassini’s work by visiting Saturn tonight? In case you hadn’t noticed, the beautiful yellowish “star” has been on the move and is now around a degree away to the southeast from a previous study star – Porrima! Not only is this a lovely visual, but an easy way to find Saturn if you’re new to the game. Seeing the Cassini Division in Saturn’s ring structure and some of the smaller moons will require at least a 114mm telescope and steady seeing. Use as much magnification as conditions will allow and look for unusual things – like seeing the planet edge through the gap!

Tonight we’ll use Rho Virginis as a stepping stone to more galaxies. Get on your mark and move one and a half degrees north for M59 (Right Ascension:12 : 42.0 – Declination: +11 : 39)…

First discovered in 1779 by J. G. Koehler while studying a comet, this 11th magnitude elliptical galaxy was observed and labeled by Messier who was just a bit behind him. Much denser than our own galaxy, M59 is only about one-fourth the size of the Milky Way. In a smaller telescope, it will appear as a faint oval, while larger telescopes will make out a more concentrated core region.

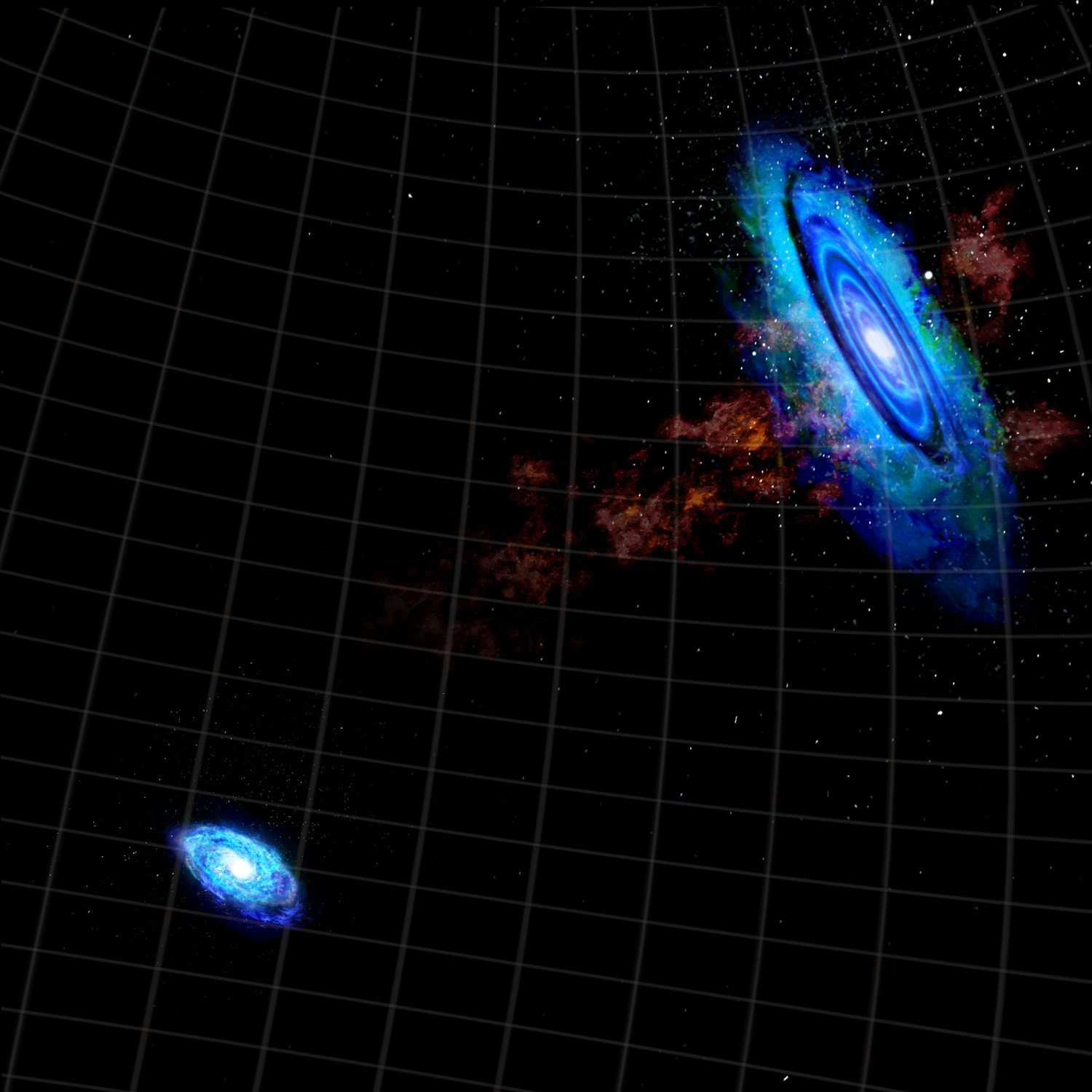

Now shift one half degree east for brighter and larger M60. Also caught first by Koehler on the same night as M59, it was “discovered” a day later by yet another astronomer who had missed M59! It took Charles Messier another four days until this 10th magnitude galaxy interfered with his comet studies and was cataloged. At around 60 million light-years away, M59 is one of the largest ellipticals known and has five times more mass than our galaxy. As a study object of the Hubble Telescope, this giant has shown a concentrated core with over 2 billion solar masses. Photographed and studied by large terrestrial telescopes, M59 may contain as many as 5100 globular clusters in its halo.

While our backyard equipment is essentially revealing M59?s core, there is a curiosity here. It shares “space” with spiral galaxy NGC 4647 (Right Ascension: 12 : 43.5 – Declination: +11 : 35). Telescopes of even modest aperture will pick up the nucleus and faint structure of this small face-on galaxy. Harlow Shapely found the pair odd because – while they are relatively close in astronomical terms – they are very different in age and development. Halton Arp also studied this combination of an elliptical galaxy affecting a spiral and cataloged it as “Peculiar Galaxy 116.” Be sure to mark your notes!

Saturday, June 9 – Today is the birthday of Johann Gottfried Galle. Born in Germany in 1812, Galle was the first observer to locate Neptune. He is also known for being Encke’s assistant – and he’s one of the few astronomers ever to have observed Halley’s Comet twice. Unfortunately, he died two months after the comet passed perihelion in 1910, but at a ripe old age of 98! I wonder if he knew Mark Twain?

Tonight while we’re out, let’s have a look at a Virgo galaxy bright enough for smaller instruments and detailed enough to delight larger scopes. Starting at Delta Virginis, move about a fistwidth to the west where you will see two fainter stars, 16 (south) and 17 (north) Virginis. You’ll find M61 (Right Ascension:12 : 21.9 – Declination: +04 : 28) located about one-half degree south of the yellow double star 17.

Its discovery was credited to Barnabus Oriani during that fateful year of 1779 when Messier was so avid about chasing a comet that he mistook it for one. While Charles had seen it on the same night, it took him two days to figure out it wasn’t moving and four more before he cataloged it. Fortunately, 7 years later Mr. Herschel assigned it his own number of H I.139, even though he wasn’t fond of assigning his own number to Messier catalog objects.

At near 10th magnitude, this spiral galaxy will show a slightly elongated form and brighter core area to small telescopes, and really come to life in larger ones. Close to our own Milky Way galaxy in size, this larger member of the Virgo cluster has great spiral arm structure that displays both knots and dark dustlanes – as well as a beautifully developed nucleus region. M61 has also been host to four supernova events between 1926 and 1999 – all of which have been well within range of amateur telescopes.

For an added Herschel treat tonight for larger scopes, hop back to star 17 and head about one half degree due west for near galactic pair NGC 4281 (H II.573) and NGC 4273 (H II.569). Here is a study of two galaxies similar in magnitude (12) and size – but of different structure. Northeastern NGC 4281 (Right Ascension: 12 : 20.4 – Declination: +05 : 23) is an elliptical, and by virtue of its central concentration will appear slightly larger and brighter – while southwestern NGC 4273 (Right Ascension: 12 : 19.9 – Declination: +05 : 21) is an irregular spiral which will appear brighter in the middle but more elongated and faded along its frontiers. Sharp-eyed observers may also note fainter (13th magnitude) NGC 4270 (Right Ascension: 12 : 19.8 – Declination: +05 : 28) north of this pairing.

Now, go back to Rho once again and about a fingerwidth northwest for yet another bright galaxy – M58 – a spiral galaxy actually discovered by Messier in 1779! As one of the brightest galaxies in the Virgo cluster, M58 (Right Ascension: 12 : 37.7 – Declination: +11 : 49) is one of only four that have barred structure. It was cataloged by Lord Rosse as a spiral in 1850. In binoculars, it will look much like our previously studied ellipticals, but a small telescope under good conditions will pick up the bright nucleus and a faint halo of structure – while larger ones will see the central concentration of the bar across the core. Chalk up another Messier study for both binoculars and telescopes and let’s get on to something really cool!

Around a half degree southwest are NGC 4567 (Right Ascension: 12 : 36.5 – Declination: +11 : 15) and NGC 4569 (Right Ascension: 12 : 36.8 – Declination: +13 : 10). L. S. Copeland dubbed them the “Siamese Twins,” but this galaxy pair is also considered part of the Virgo cluster. While seen from our viewpoint as touching galaxies, no evidence exists of tidal filaments or distortions in structure, making them a line of sight phenomenon and not interacting members. While that might take little of the excitement away from the “Twins,” a supernova event has been spotted in NGC 4569 as recently as 2004. While the duo is visible in smaller scopes as two, with soft twin nuclei, intermediate and larger scopes will see an almost V-shaped or heart-shaped pattern where the structures overlap. If you’re doing double galaxy studies, this is a fine, bright one! If you see a faint galaxy in the field as well, be sure to add NGC 4564 (Right Ascension: 12 : 36.4 – Declination: +11 : 26) to your notes.

Sunday, June 10 – While I’m sure that unaided eye viewers and binocular users are tired of the galaxy hunt, be sure to take the time to look at many old favorites that are now in view. To the eye, one of the most splendid signs of the changing seasons is the Ursa Major Moving Group which sits above Polaris for northern hemisphere observers. For the southern hemisphere, the return of Crux serves the same purpose.

Old favorites have now begun to appear again, such as Hercules, Cygnus and Scorpius… and with them a wealth of starry clusters and nebulae that will soon come into view as the night deepens and the hour grows late. Before we leave Virgo for the year, there is one last object that is seldom explored and such a worthy target that we must visit it before we go. Its name is NGC 5634 and you’ll find it halfway between Iota and Mu Virginis (RA 14 29.37 Dec -05 58.35)…First discovered by Sir William Herschel on March 5, 1785 and cataloged as H I.70, this magnitude 9.5 small globular cluster isn’t for everyone, but thanks to an 11th magnitude line-of-sight star on its eastern edge, it sure is interesting. At class IV, it’s more concentrated than many globular clusters, although its 19th magnitude members make it near impossible to resolve with backyard equipment.

Located a bit more than 82,000 light-years from our solar system and about 69,000 light-years from the galactic center, you’ll truly enjoy this globular for the randomly scattered stellar field which accompanies it. In the finderscope, an 8th magnitude star will lead the way – not truly a member of the cluster, but one that lies between us. Capturable in scopes as small as 4.5?, look for a concentrated central area surrounded by a haze of stellar members – a huge number of which are recently discovered variables. While you look at this globular, keep this in mind… Based on observations with the Italian Telescopio Nazionale Galileo, it is now surmised that the NGC 5634 globular cluster has the same position and radial velocity as does the Sagittarius dwarf spheroidal galaxy. Because of the dwarf galaxy’s metal-poor population of stars, it is believed that NGC 5634 may have once been part of the dwarf galaxy – and been pulled away by our own tidal field to become part of the Sagittarius stream!

Until next week? Wishing you clear skies for the Partial Lunar Eclipse, Venus Transit and the meteor showers!

Still, despite the isolation, darkness and cold, Dr. Kumar finds inspiration in his surroundings.

Still, despite the isolation, darkness and cold, Dr. Kumar finds inspiration in his surroundings.