[/caption]

Supernova explosions and the jets of a monstrous black hole are scattering one galaxy’s star-making gas, driving a dramatic transformation from spiral galactic youth to elderly elliptical, according to a new study of a recently merged galaxy. Cool gas, the fuel from which new stars form, is essential to the youth and vigor of a galaxy. But supernova explosions can start the decline in star formation, and then shock waves from the supermassive black hole finish the job, turning spiral galaxies to “red and dead” ellipticals.

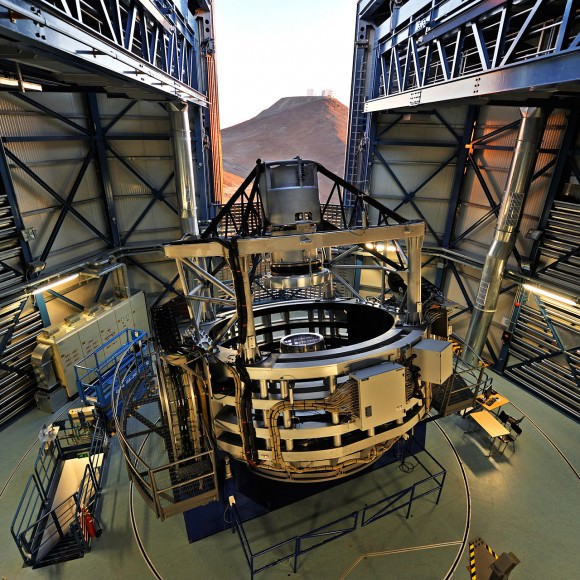

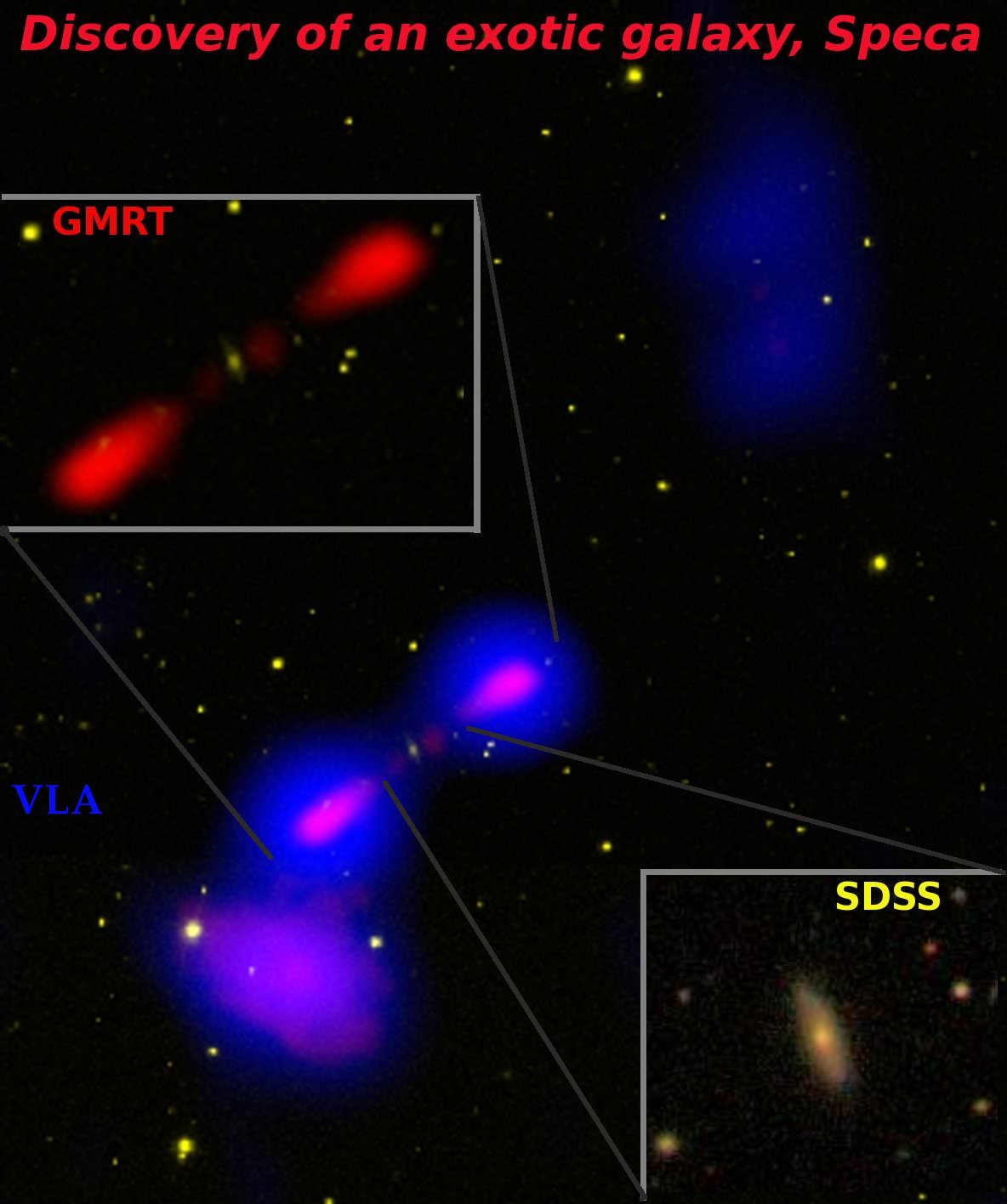

Astronomers think they have identified a recently merged galaxy, NGC 3801, where this gas loss has just gotten underway. Using ultraviolet observations from NASA’s Galaxy Evolution Explorer (GALEX) and a host of other instruments, the new findings fill an important gap in the current understanding of galactic evolution.

“We have caught a galaxy in the act of destroying its gaseous fuel for new stars and marching toward being a red-and-dead type of galaxy,” said Ananda Hota, lead author of a new paper in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. “We have found a crucial missing piece to connect and solve the puzzle of this phase of galaxy evolution.”

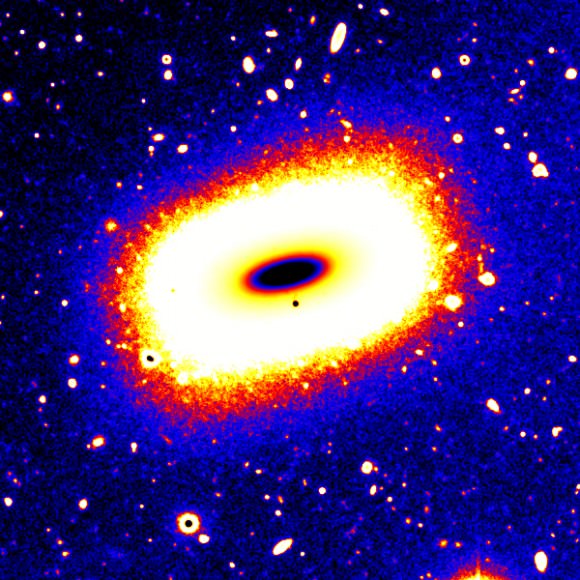

It has long been known that gas-rich spiral galaxies like our Milky Way smash together to create elliptical galaxies such as the one observed in the study. These big, round galaxies have very little star formation.

The supermassive black holes that reside in the centers of galaxies can flare up when engorged by gas during galactic mergers. As a giant black hole feeds, colossal jets of matter shoot out from it, giving rise to what is known as an active galactic nucleus. According to theory, shock waves from these jets heat up and disperse the reservoirs of cold gas in elliptical galaxies, thus preventing new stars from taking shape.

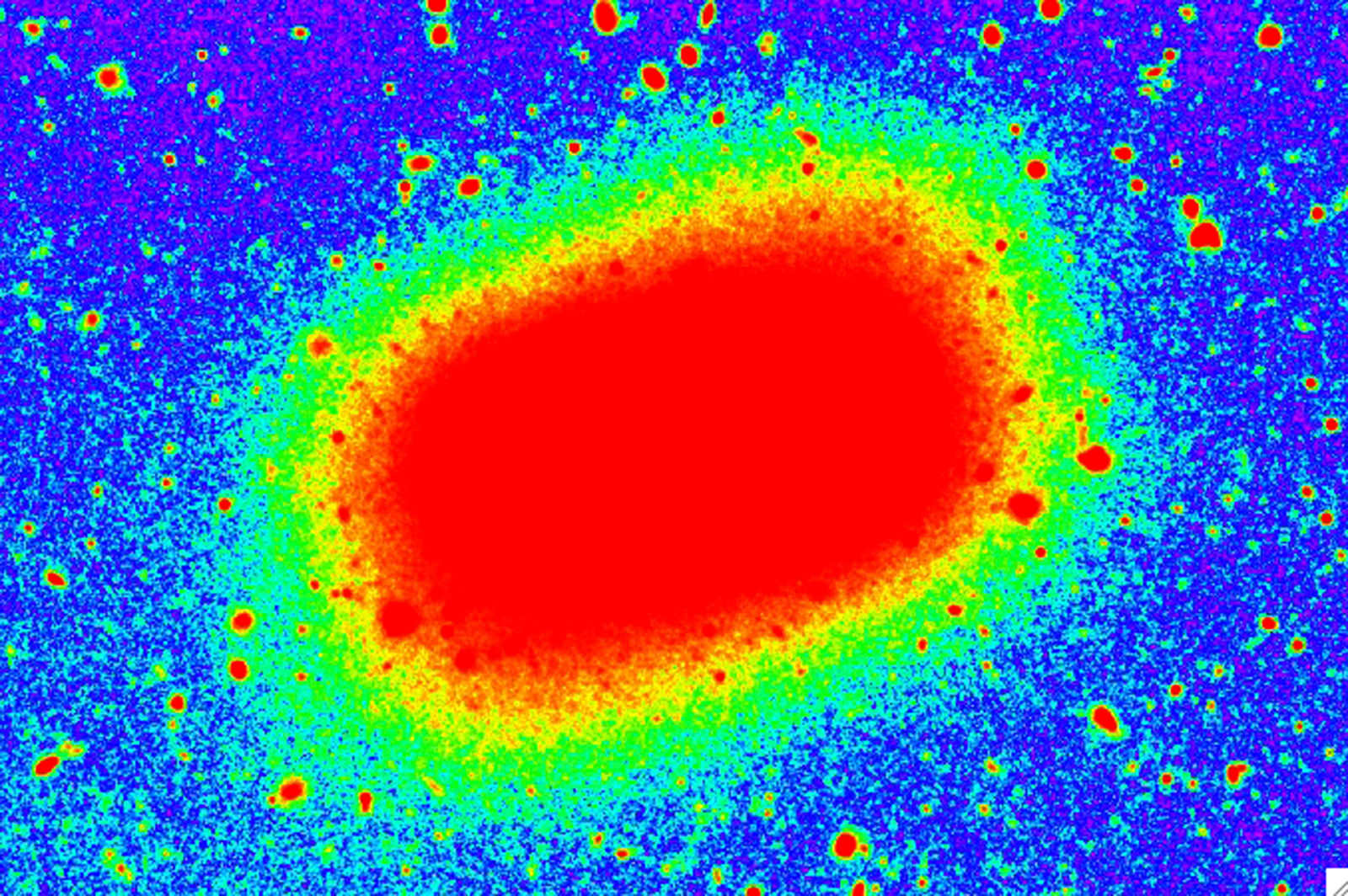

NGC 3801 shows signs of such a process. This galaxy is unique in that evidence of a past merger is clearly seen, and the shock waves from the central black hole’s jets have started to spread out very recently. The researchers used the Galaxy Evolution Explorer to determine the age of the galaxy’s stars and decipher its evolutionary history. The ultraviolet observations show that NGC 3801’s star formation has petered out over the last 100 to 500 million years, demonstrating that the galaxy has indeed begun to leave behind its youthful years. The lack of many big, new, blue stars makes NGC 3801 look yellowish and reddish in visible light, and thus middle-aged.

What’s causing the galaxy to age and make fewer stars? The short-lived blue stars that formed right after it merged with another galaxy have already blown up as supernovae. Data from NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope revealed that those stellar explosions have triggered a fast outflow of heated gas from NGC 3801’s central regions. That outflow has begun to banish the reserves of cold gas, and thus cut into NGC 3801’s overall star making.

Some star formation is still happening in NGC 3801, as shown in ultraviolet wavelengths observed by the Galaxy Evolution Explorer, and in infrared wavelengths detected by NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope. But that last flicker of youth will soon be extinguished by colossal shock waves from the black hole’s jets, seen in X-ray light by NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory. These blast waves are rushing outward from the galactic center at a velocity of nearly two million miles per hour (nearly 900 kilometers per second). The waves will reach the outer portions of NGC 3801 in about 10 million years, scattering any remaining cool hydrogen gas and rendering the galaxy truly red and dead.

Astronomers think the transition captured early-on in the case of NGC 3801 — from the merger of gas-rich galaxies to the rise of an old-looking elliptical — happens very quickly on cosmic time scales.

“The quenching of star formation by feedback from the active galactic nucleus probably occurs in just a billion years. That’s not very long compared to the 10-billion-year age of a typical big galaxy,” said Hota. “The explosive shock wave event caused by the central black hole is so powerful that it can dramatically change the future course of the evolution of an entire galaxy.”

Additional observations for the study in optical light come from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey and in radio using the Very Large Array in New Mexico.

Hota is an astronomer in Pune, India, conducted the study as a post-doctoral research fellow at the Institute of Astronomy & Astrophysics at Academia Sinica in Taipei, Taiwan.