[/caption]

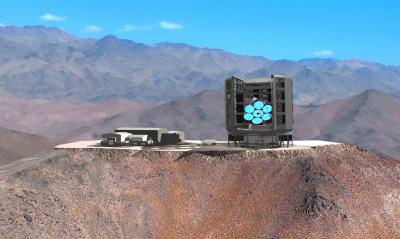

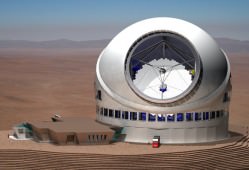

Astronomy organizations in the United States, Australia and Korea have signed on to build the largest ground-based telescope in the world – unless another team gets there first. The Giant Magellan Telescope, or GMT, will have the resolving power of a single 24.5-meter (80-foot) primary mirror, which will make it three times more powerful than any of the Earth’s existing ground-based optical telescopes. Its domestic partners include the Carnegie Institution for Science, Harvard University, the Smithsonian Institution, Texas A & M University, the University of Arizona, and the University of Texas at Austin. Although the telescope has been in the works since 2003, the formal collaboration was announced Friday.

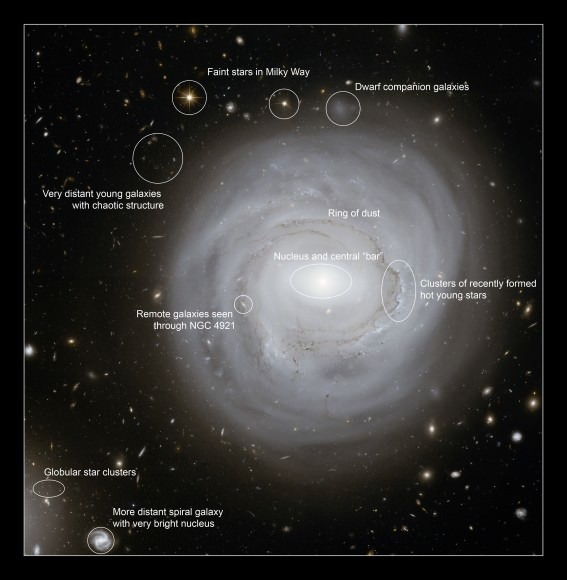

Charles Alcock, director of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, said the Giant Magellan Telescope is being designed to build on the legacy of a rash of smaller telescopes from the 1990s in California, Hawaii and Arizona. The existing telescopes have mirrors in the range of six to 10 meters (18 to 32 feet), and – while they’re making great headway in the nearby universe – they’re only able to make out the largest planets around other stars and the most luminous distant galaxies.

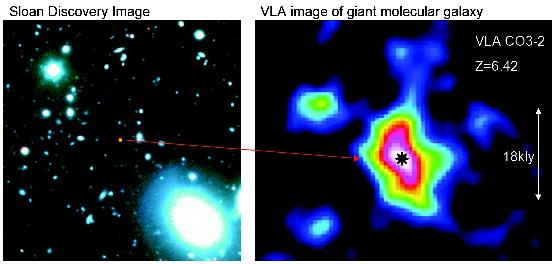

With a much larger primary mirror, the GMT will be able to detect much smaller and fainter objects in the sky, opening a window to the most distant, and therefore the oldest, stars and galaxies. Formed within the first billion years of the Big Bang, such objects reveal tantalizing insight into the universe’s infancy.

Earlier this year, a different consortium including the California Institute of Technology and the University of California, with Canadian and Japanese institutions, unveiled its own next-generation concept: the Thirty Meter Telescope. Whereas the GMT’s 24.5-meter primary mirror will come from a collection of eight smaller mirrors, the TMT will combine 492 segments to achieve the power of a single 30-meter (98-foot) mirror design.

In addition, the European Extremely Large Telescope is in the concept stage.

In terms of science, Alcock acknowledged that the two telescopes with US participation are headed toward redundancy. The main differences, he said, are in the engineering arena.

“They’ll probably both work,” he said. But Alcock thinks the GMT is most exciting from a technological point of view. Each of the GMT’s seven 8.4-meter primary segments will weigh 20 tons, and the telescope enclosure has a height of about 200 feet. The GMT partners aim to complete their detailed design within two years.

The TMT’s segmented concept builds on technology pioneered at the W.M. Keck Observatory in Hawaii, a past project of the Cal-Tech and University of California partnership.

Construction on the GMT is expected to begin in 2012 and completed in 2019, at Las Campanas Observatory in the Andes Mountains of Chile. The total cost is projected to be $700 million, with $130 million raised so far.

Construction on the TMT could begin as early as 2011 with an estimated completion date of 2018. The telescope could go to Hawaii or Chile, and final site selection will be announced this summer. The total cost is estimated to be as high as $1 billion, with $300 million raised at last count.

Alcock said the next generation of telescopes is crucial for forward progress in 21st Century astronomy.

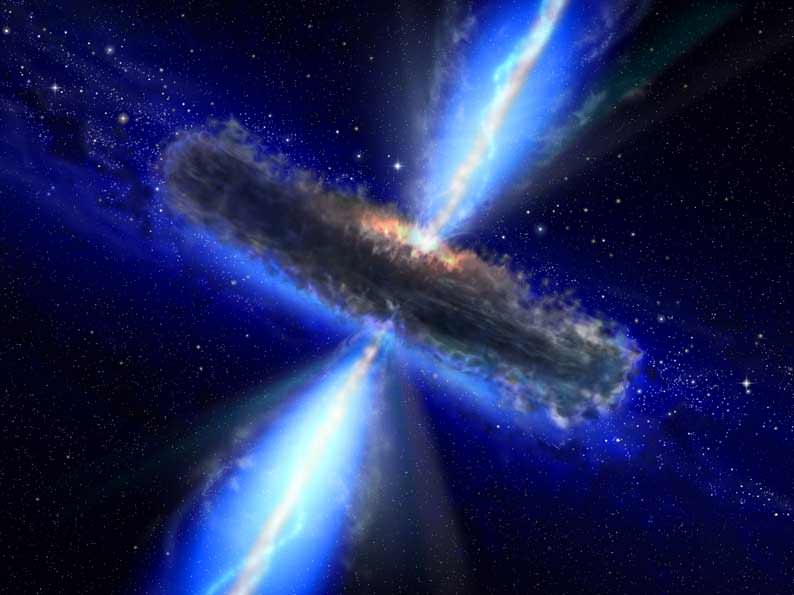

“The goal is to start discovering and characterizing planets that might harbor life,” he said. “It’s very clear that we’re going to need the next generation of telescopes to do that.”

And far from being a competition, the real race is to contribute to science, said Charles Blue, a TMT spokesman.

“All next generation observatories would really like to be up and running as soon as possible to meet the scientific demand,” he said.

In the shorter term, long distance space studies will get help from the James Webb Space Telescope, designed to replace the Hubble Space Telescope when it launches in 2013. And the Atacama Large Millimeter Array (ALMA), a large interferometer being completed in Chile, could join the fore by 2012.

Sources: EurekAlert and interviews with Charles Alcock, Charles Blue