[/caption]

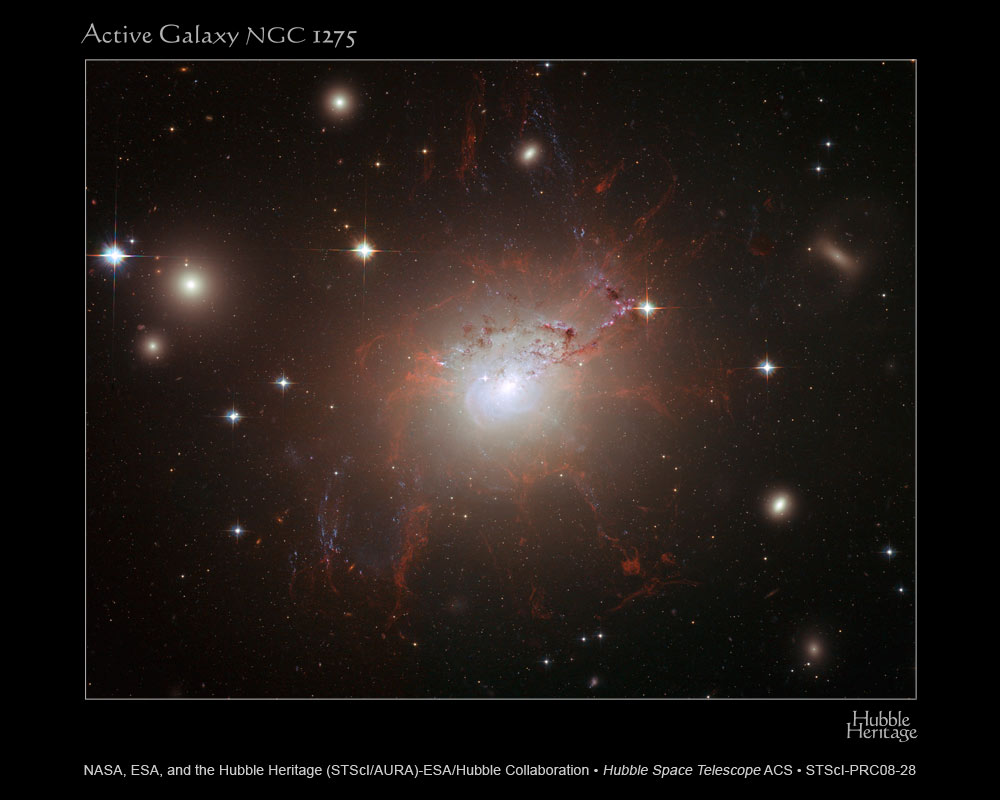

Everyone is suffering from severe angst about the fate of the Hubble Space Telescope, and now, on the heels of Hubble’s data controller failure news comes more ANGST. But this is a good ANGST – which is an acronym for ACS Nearby Galaxy Survey Treasury. The Advanced Camera for Surveys (ACS) has completed a thorough survey of galaxies in our cosmic backyard, providing clues about how stars form. Using Hubble, astronomers observed around 14 million stars in 69 galaxies, ranging from 6.5 million light-years to 13 million light-years from Earth. Interestingly, some galaxies were found to be full of ancient stars, while others are like sun-making factories. So, if you’re suffering from Hubble angst, peruse the images from this newest survey – they may bring you comfort. Either that, or you’ll cry from sorrow of what could possibly be lost… (no, no, no — think happy thoughts!!!)…

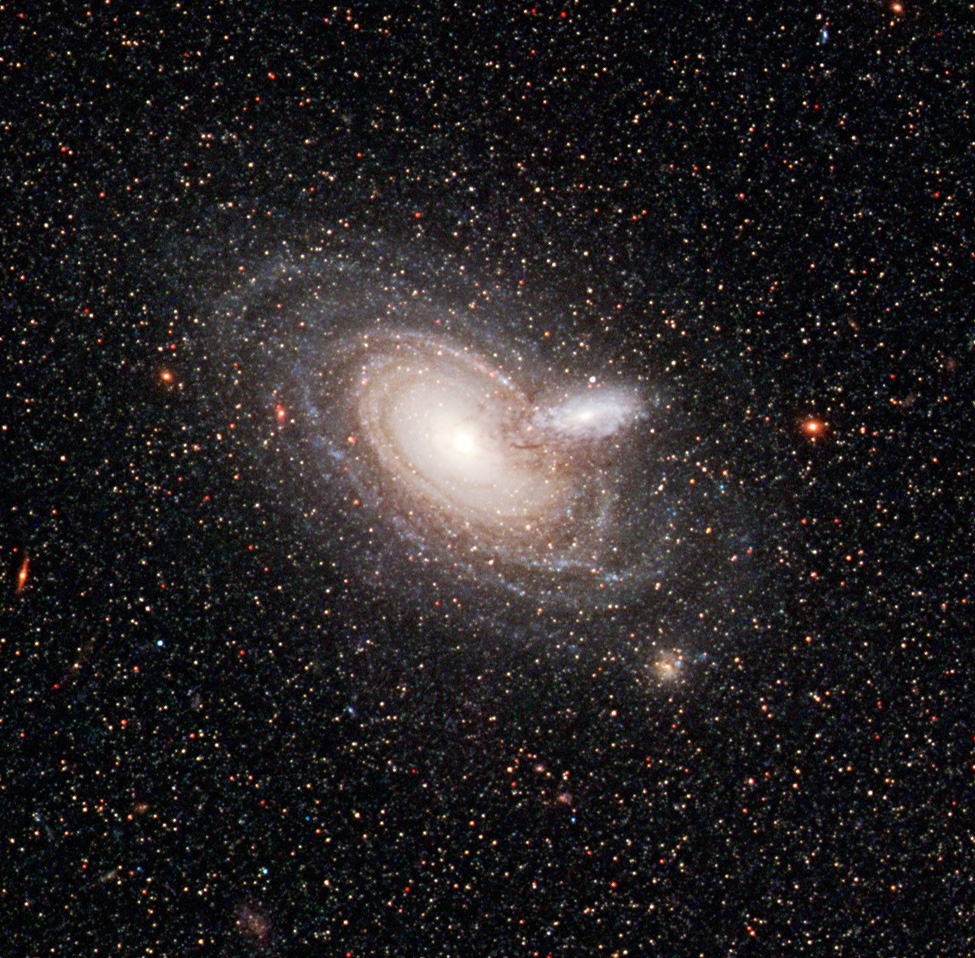

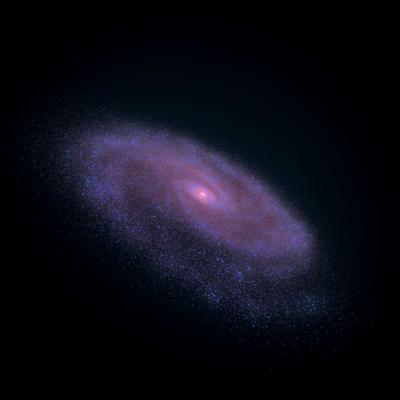

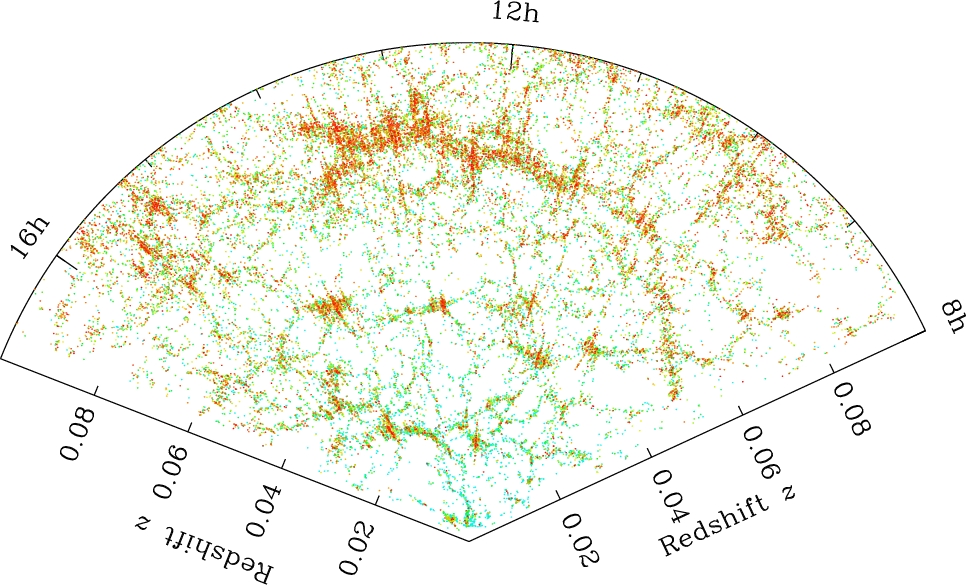

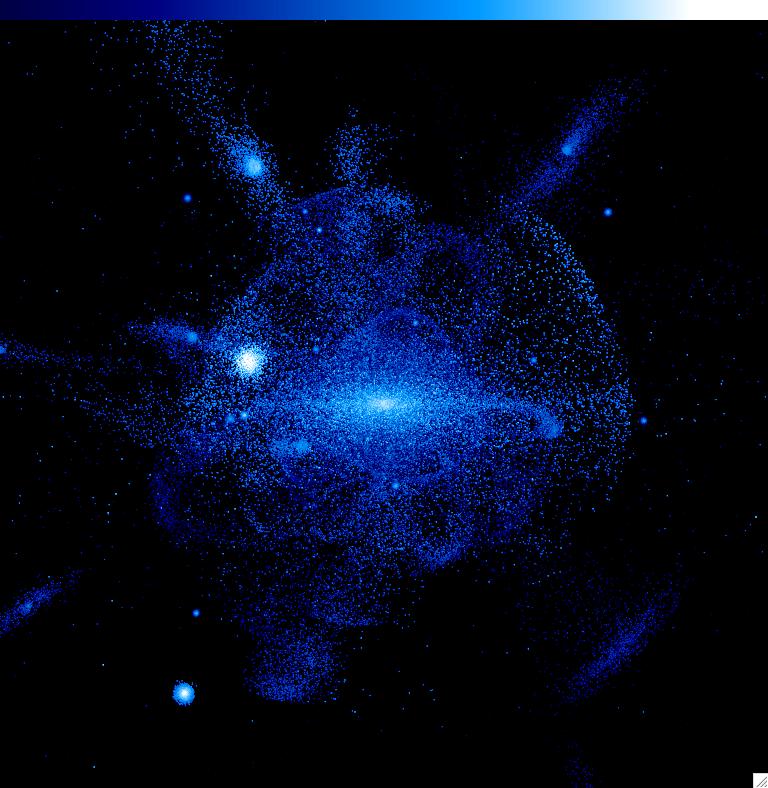

The detailed survey, called the ACS Nearby Galaxy Survey Treasury (ANGST) program, explored a region called the Local Volume of galaxies. A typical galaxy contains billions of stars but looks smooth when viewed through a conventional telescope because the stars appear blurred together. In contrast, the galaxies observed in this new survey are close enough to Earth that the sharp view provided by Hubble’s Advanced Camera for Surveys and Wide Field Planetary Camera 2 can resolve the brightness and color of some individual stars. This allows scientists to determine the history of star formation within a galaxy and tease out subtle features in a galaxy’s shape.

“Past Hubble observations of the local neighbourhood have provided dramatic insights into the star-formation histories of individual galaxies, but the number of galaxies studied in detail has been rather small”, said Julianne Dalcanton of the University of Washington in Seattle (USA) and leader of the ANGST survey. “Instead of picking and choosing particular galaxies to study, our survey will be complete by virtue of looking at ‘all’ the galaxies in the region. This gives us a multi-colour picture of when and where all the stars in the local Universe formed.”

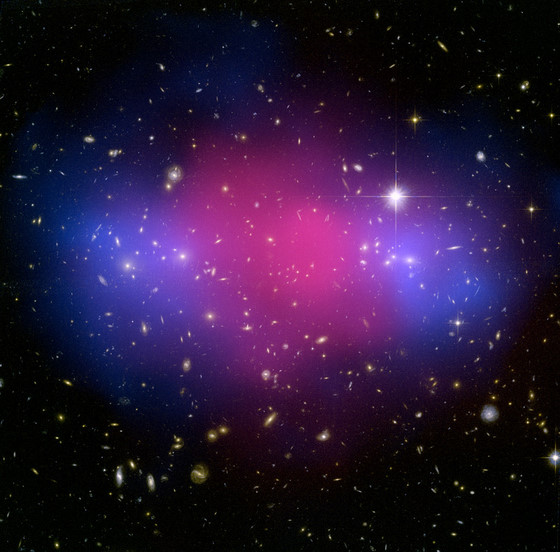

Many stars in nearby galaxies are the fossil equivalents of new stars forming in the far Universe, and these latest images provide a “fossil record” for stars, providing a better understanding of the masses, structures, and environments of the galaxies.”

Early results of the ANGST survey show the rich diversity of galaxies. Some are made up entirely of ancient stars, while others have been forming stars nearly continuously during their whole lives. There are even a few examples of galaxies that have only started forming stars in the recent past. “With these images, we can see what makes each galaxy unique”, said team member Benjamin Williams of the University of Washington.

The ANGST survey also includes maps of many large galaxies, including M81. “With these maps, we can track when the different parts of the galaxy formed”, explained Evan Skillman of the University of Minnesota (USA), describing work by students Dan Weisz of the University of Minnesota and Stephanie Gogarten of the University of Washington.

“This rich survey will add to Hubble’s legacy, providing a foundation for future studies”, Dalcanton added. “With this information, we will be able to trace the complete cycle of star formation in detail.”

So, check out the images from this survey and all the wonderful, amazing, and incredible Hubble images to help ease your Hubble angst.

Source: HubbleSite