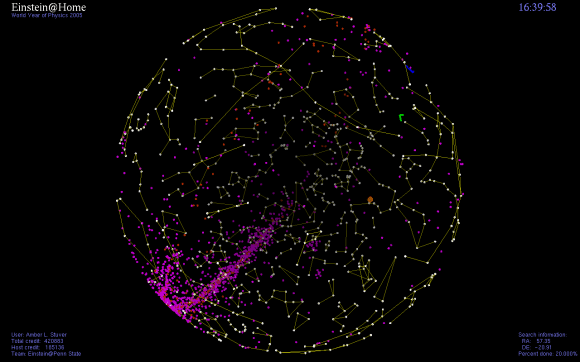

Vigilance and a little luck paid off recently for an amateur astronomer.

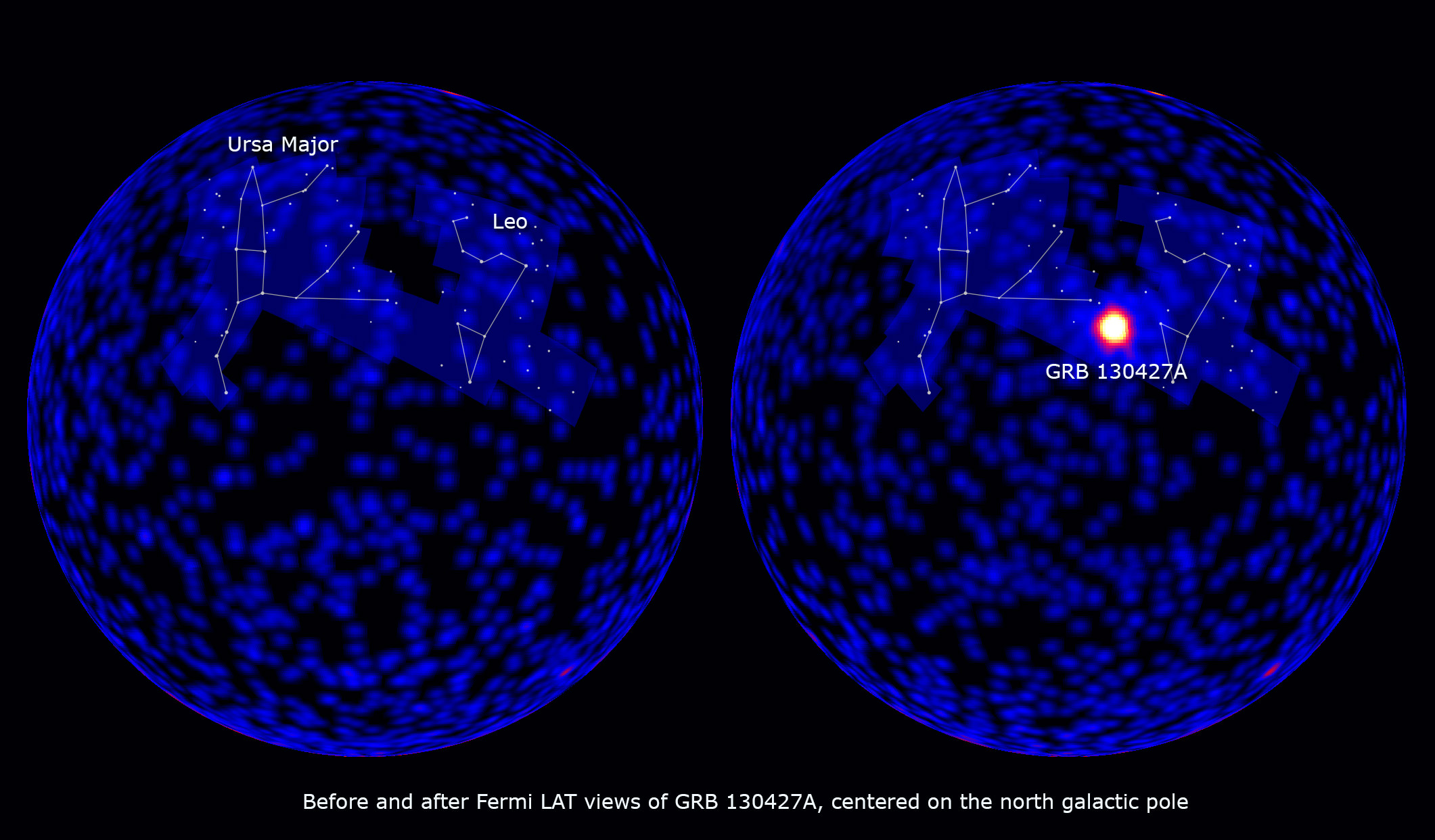

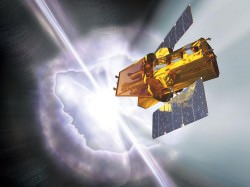

On April 27th, 2013 a long lasting gamma-ray burst was recorded in the northeastern section of the constellation Leo. As reported here on Universe Today, the burst was the most energetic ever seen, peaking at about 94 billion electron volts as seen by Fermi’s Large Area Telescope. In addition to Fermi’s Gamma Ray Burst Monitor, the Swift satellite and a battery of ground based instruments also managed to quickly swing into action and record the burst as it was underway.

But professionals weren’t the only ones to capture the event. Amateur astronomer Patrick Wiggins was awake at the time, doing routine observations from his observatory based near Toole, Utah when the alert message arrived. He quickly swung his C-14 telescope into action at the coordinates of the burst at 11 Hours 32’ and 33” Right Ascension and +27° 41’ 56” declination.

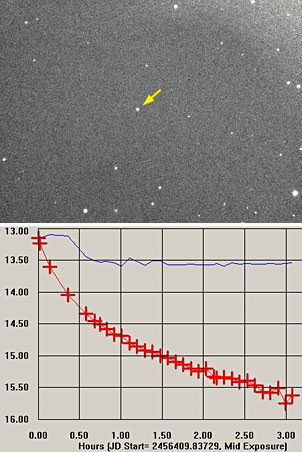

Wiggins then began taking a series of 60-second exposures with his SBIG ST-10XME imager and immediately found something amiss. A 13th magnitude star had appeared in the field. At first, Wiggins believed this was simply too bright to be a gamma-ray burst transient, but he continued to image the field into the morning of April 27th.

Wiggins had indeed caught his optical prey, the very first gamma-ray burst he’d captured. And what a burst it was. At only 3.6 billion light years distant, GRB 130427A (gamma-ray bursts are named after the year-month-day of discovery) was one for the record books, and in the top five percent of the closest bursts ever observed.

Mr. Wiggins further elaborated the fascinating story of the observation to Universe Today:

“I was imaging an area near where the burst occurred and received an email GCN Circular and a GCN/SWIFT Notice of the event within minutes of it happening. As bad luck would have it I was in the kitchen fixing a late night snack when both arrived so I was about 10 minutes late reading them.

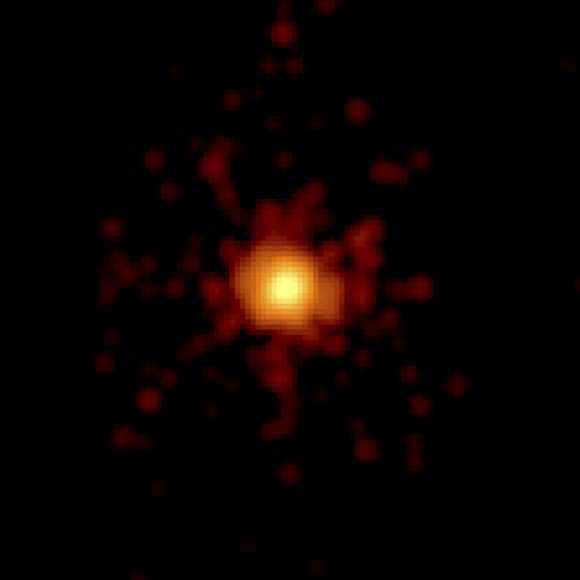

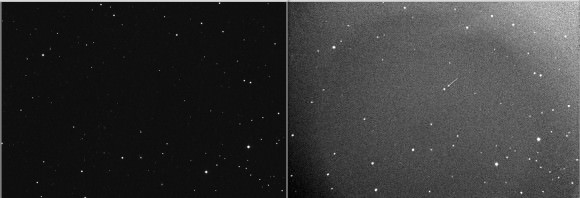

I figured that 10 minutes was way too late as these things typically only last a minute or two but I slewed to the coordinates indicated in the notices and shot a quick picture. There was a bright “something” in the middle of the frame as shown here with the POSS comparison image:”

“But I thought it looked way too bright for a GRB so I moved the telescope slightly (to see if the object was a ghost or an artifact in the system) and shot again but it was still there.

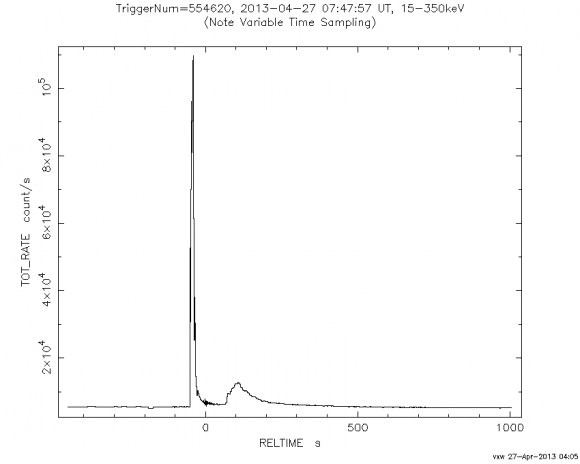

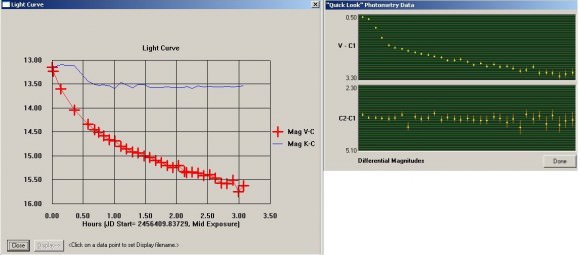

A quick check of the POSS showed nothing should be there so I started shooting pictures at five minute intervals until dawn and it was those images I used to put together the light curve:”

Amazingly, the RAPTOR (RAPid Telescopes for Optical Response) array recorded a peak brightness in optical wavelengths of magnitude +7.4 just less than a minute before the Swift spacecraft swung into action. This is just below the dark sky limiting naked-eye magnitude of +6. This is also just below the record optical brightness set by GRB 080319B, which briefly reached magnitude +5.3 back in 2008.

RAPTOR is run by the Los Alamos National Laboratory and is based at Fenton Hill Observatory in the Jemez Mountains of New Mexico 56 kilometres west of Los Alamos.

The Catalina Real-Time Transient Survey based outside of Tucson Arizona also detected the burst independently, giving it the designation CSS130502: 113233+274156. The burst occurred less than a degree from the +13th magnitude galaxy NGC 3713, and the galaxy SDSS J113232.84+274155.4 is also very close to the observed position of the burst.

Mr. Wiggins’ observation also raises an intriguing possibility. Did anyone catch a surreptitious image of the burst? Anyone wide-field imaging right around the three-way junction of the constellations Ursa Major, Leo & Leo Minor at the correct time might just have caught GRB 130427A in the act. Make sure to review those images!

Follow up observations of gamma-ray bursts are just one of the ways that amateur backyard observers continue to contribute to the science of astronomy. Observers such as Mr. Wiggins and James McGaha based at the Grasslands Observatory near Sonita, Arizona routinely swing their equipment into action chasing after optical transients as alert messages for gamma-ray events are received.

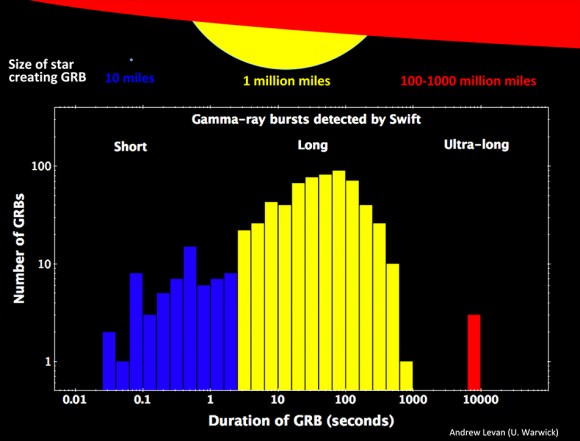

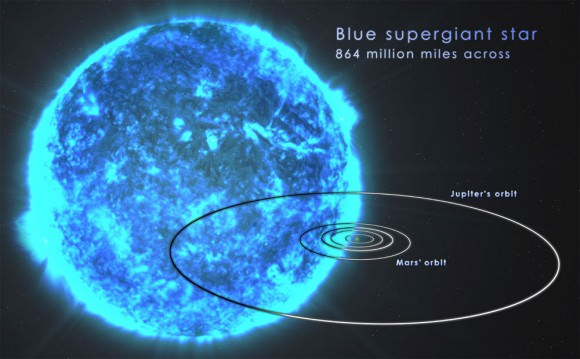

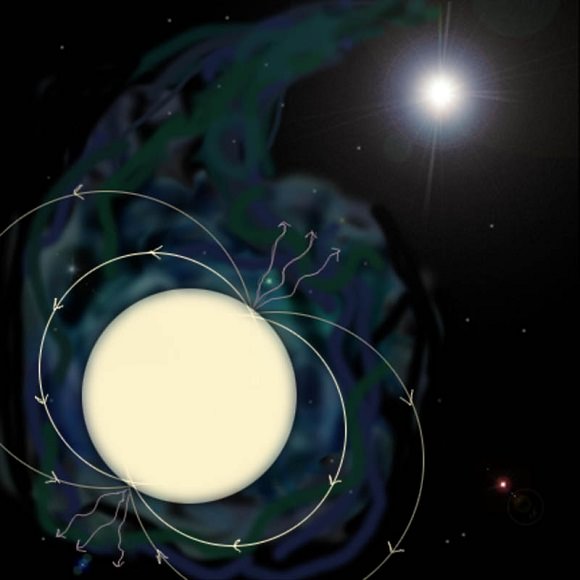

Gamma-ray bursts where first discovered in 1967 by the Vela spacecraft designed to monitor nuclear weapons testing during the Cold War. They come in two varieties: short period and long duration bursts. Short period bursts of less than two seconds duration are thought to occur when a binary pulsar pair merges, while long duration bursts such as GRB 130427A occur when a massive red giant star undergoes a core collapse and shoots a high energy jet directly along its poles in a hypernova explosion. If the burst is aimed in our direction, we get to see the event. Thankfully, no possible progenitors of a long duration gamma-ray burst lie aimed at us in our galaxy, though the Wolf-Rayet stars Eta Carinae and WR 104 both about 8,000 light years distant are worth keeping an eye on. Luckily, neither of these massive stars is known to have rotational poles tipped in our general direction.

Scary stuff to consider as we hunt for the next “Big One” in the night sky. In the meantime, we’ve got much to learn from gamma-ray bursts such as GRB 130427A. Congrats to Mr. Wiggins on his first gamma-ray burst observation… the event was made all the more special by the fact that it occurred on his birthday!

-Mr Patrick Wiggins is NASA/JPL Ambassador to the state of Utah.

– Read the American Association of Variable Star Observers (AAVSO) report of the light curve of GRB 130427A as reported by Mr. Wiggins here.

– NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center maintains a clearing house of the latest GRB alerts in near-real-time here.

– You can also now receive GRB alerts via @Gammaraybursts on Twitter, as well as follow NASA’s Swift and Fermi missions.

– And of course, “there’s an App for that” in the world of GRB alerts in the form of the free Swift Explorer App for the Iphone.