[/caption]

Compact, ultrabright jets at supermassive black holes in active galaxies were already known to pack an impressive punch in radio waves. And now, an international team of scientists says they’re kicking out high-energy gamma rays too.

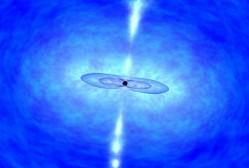

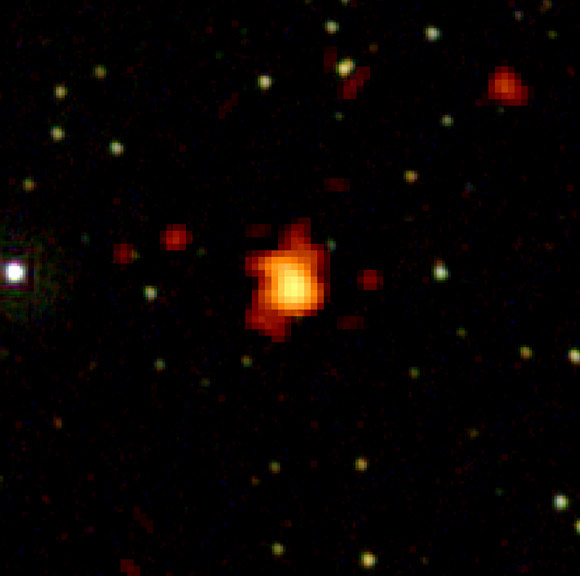

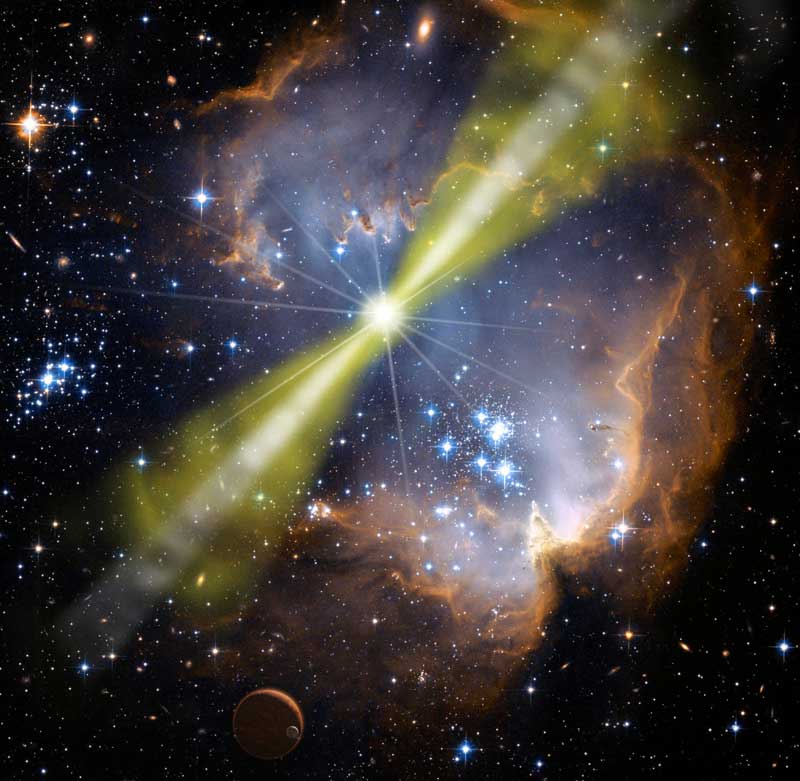

Distant galaxies host the super massive black holes, which are billions of times heavier than our Sun but are confined to a region no larger than our solar system. The rapidly rotating black holes attract stars, gas and dust, creating huge magnetic fields. The magnetic forces can trap some of the infalling gas and focus it into narrow jets that flow away from the core of the galaxy at velocities approaching the speed of light.

Theoreticians and observers alike have been puzzling for decades about the nature and composition of these energetic radio-emitting jets, and if they also radiate in other parts of the electromagnetic spectrum.

Some hints were provided by the EGRET instrument on the Compton Gamma Ray Observatory telescope in the late 1990s and more recent discoveries of X-ray emission made by the Chandra Observatory.

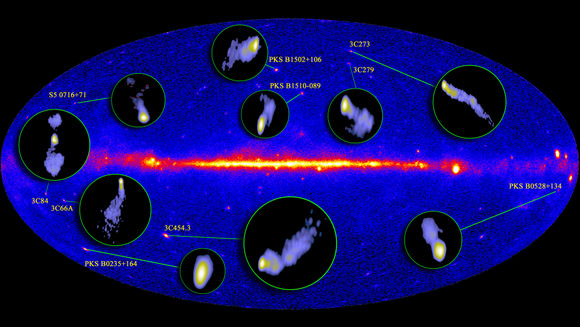

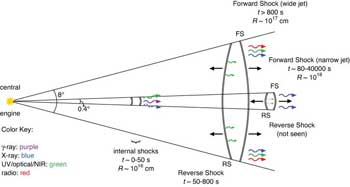

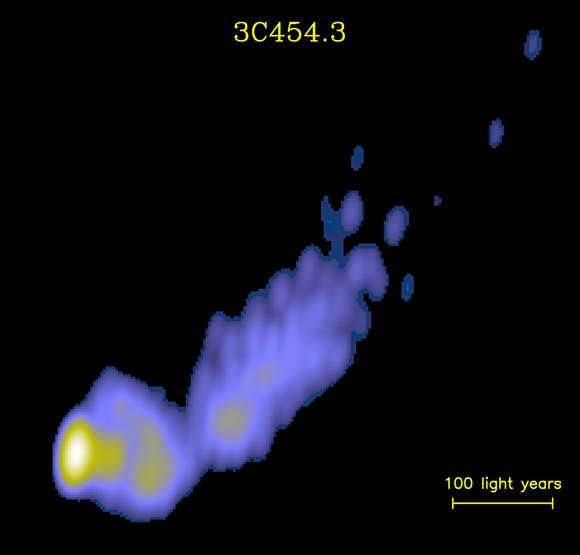

Now, astronomers from Germany, the United States and Spain have paired observations of the bright gamma-ray sky by NASA’s orbiting Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope with those from the ground-based Very Long Baseline Array radio telescope in the United States to observe the material expelled with enormous speeds away from the black holes in the heart of very remote galaxies. These ejections take the form of narrow jets in radio telescope images, and appear to be producing the gamma-rays detected by Fermi.

“These objects are amazing: finally we know for sure that the fastest, most compact, and brightest jets that we see with radio telescopes are the ones which are able to kick the light up to the highest energies,” said Yuri Kovalev, Humboldt Fellow and scientist at the Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy.

The gamma-ray bright sources are now shown to be brighter, more compact and faster at light year scales than the gamma-ray quiet sources.

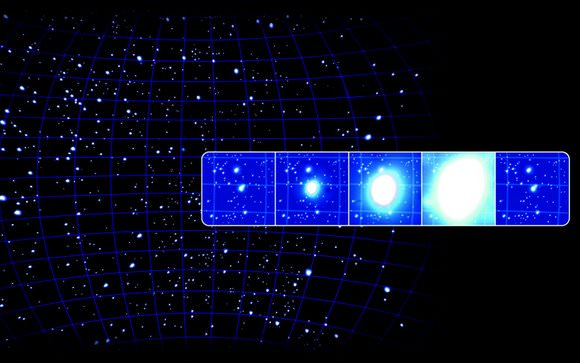

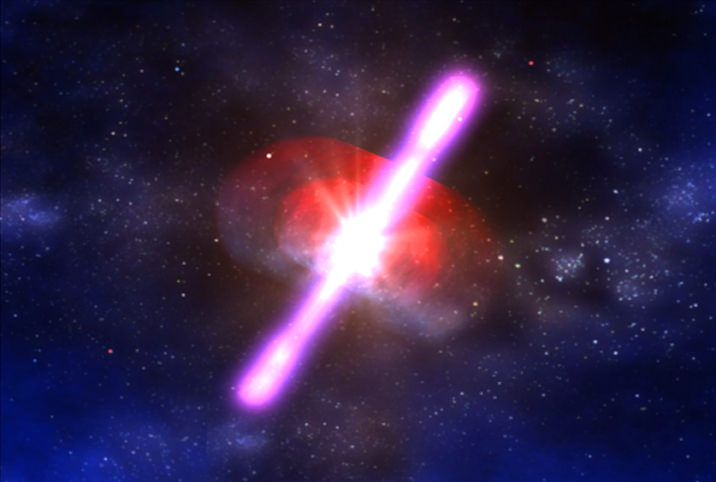

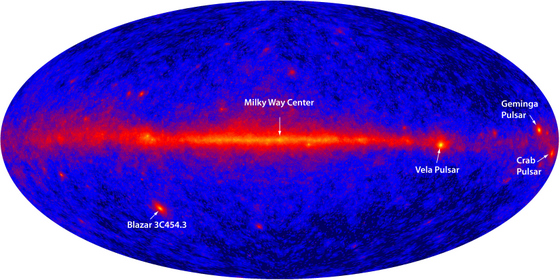

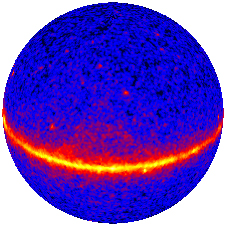

Fermi, formerly known as GLAST, has been operational since the summer of 2008. The telescope records an image of the whole sky every few hours to explore the most extreme environments in the universe, including pulsars and gamma-ray bursts, as well as black holes in galactic nuclei. Gamma-ray observations alone are not enough to discern the exact location of the radiation, however. The VLBA serves as a magnifying glass for zeroing in on the most energetic processes in the distant universe. Many objects found by Fermi to be extreme in gamma-rays are emitting strong bursts of radio emission at the same time.

The Very Long Baseline Array is a continent-wide system of ten radio telescope antennas, ranging from Hawaii in the west to the U.S. Virgin Islands in the east. Dedicated in 1993, the VLBA is operated by the U.S. National Radio Astronomy Observatory and is designed to monitor the brightest objects in the Universe at the highest available resolution in astronomy.

The work for astronomers does not stop here: the team has concluded that the region of the jet closest to the black hole is undoubtedly the place where the gamma-ray and the radio bursts of light originate in about the same time. However, some parts of the puzzle have yet to be resolved, they say: some bright gamma-ray sources in the sky appear to have no radio or optical counterpart — their nature is still completely unknown.

Source: Max-Planck Institute. The findings are being reported in two publications in the May 1, 2009 issue of Astrophysical Journal Letters (here and here).

Links:

Very Long Baseline Array

VLBA Monitoring of AGN Jets: The MOJAVE Project

Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope LAT Group