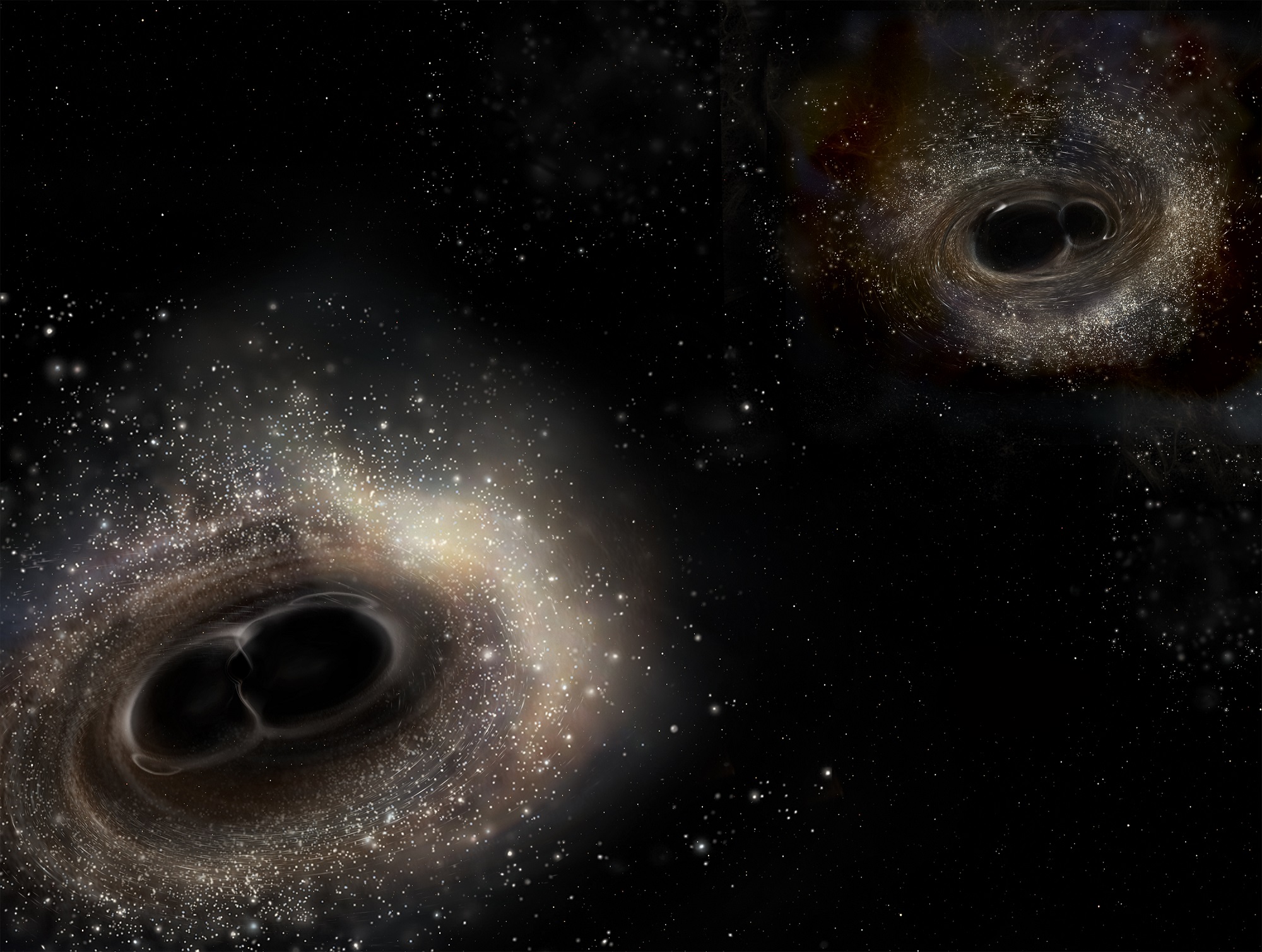

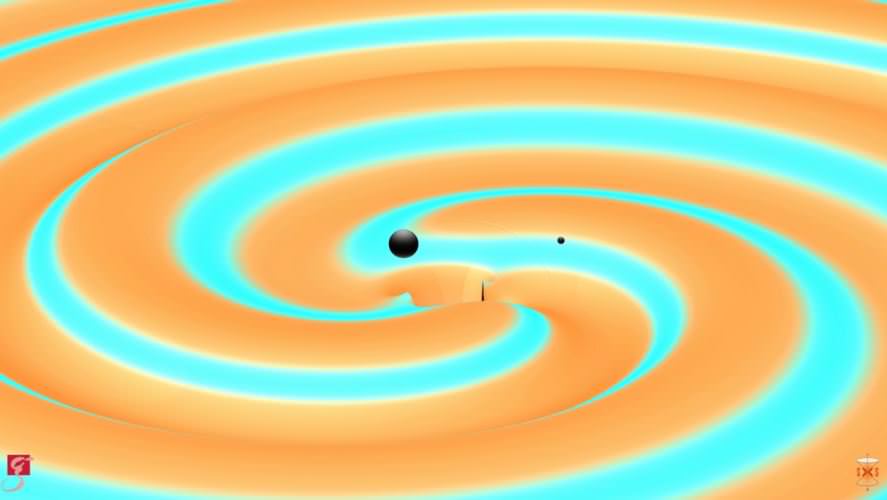

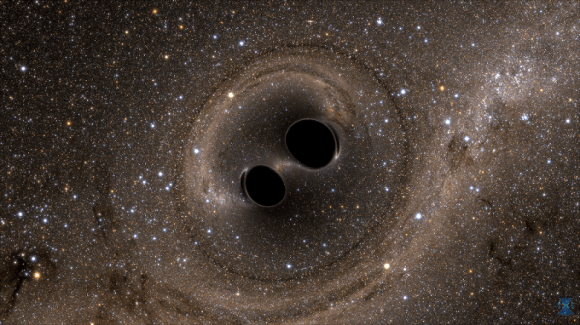

On February 11th, 2016, scientists at the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-wave Observatory (LIGO) announced the first detection of gravitational waves. This development, which confirmed a prediction made by Einstein’s Theory of General Relativity a century ago, has opened up new avenues of research for cosmologists and astrophysicists. Since that time, more detections have been made, all of which were said to be the result of black holes merging.

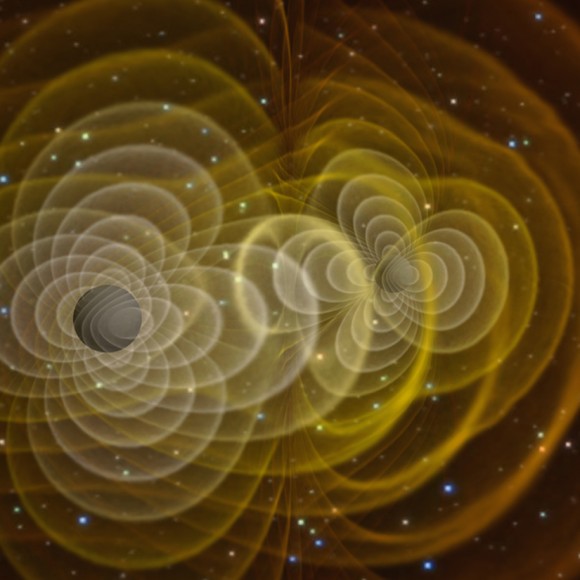

The latest detection took place on August 14th, 2017, when three observatories – the Advanced LIGO and the Advanced Virgo detectors – simultaneously detected the gravitational waves created by merging black holes. This was the first time that gravitational waves were detected by three different facilities from around the world, thus ushering in a new era of globally-networked research into this cosmic phenomena.

The study which detailed these observations was recently published online by the LIGO Scientific Collaboration and the Virgo Collaboration. Titled “GW170814 : A Three-Detector Observation of Gravitational Waves from a Binary Black Hole Coalescence“, this study has also been accepted for publication in the scientific journal Physical Review Letters.

The event, designated as GW170814, was observed at 10:30:43 UTC (06:30:43 EDT; 03:30:43 PDT) on August 14th, 2017. The event was detected by the National Science Foundation‘s two LIGO detectors (located in Livingston, Louisiana, and Hanford, Washington) and the Virgo detector located near Pisa, Italy – which is maintained by the National Center for Scientific Research (CNRS) and the National Institute for Nuclear Physics (INFN).

Though not the first instance of gravitational waves being detected, this was the first time that an event was detected by three observatories simultaneously. As France Córdova, the director of the NSF, said in a recent LIGO press release:

“Little more than a year and a half ago, NSF announced that its Laser Interferometer Gravitational Wave Observatory had made the first-ever detection of gravitational waves, which resulted from the collision of two black holes in a galaxy a billion light-years away. Today, we are delighted to announce the first discovery made in partnership between the Virgo gravitational-wave observatory and the LIGO Scientific Collaboration, the first time a gravitational wave detection was observed by these observatories, located thousands of miles apart. This is an exciting milestone in the growing international scientific effort to unlock the extraordinary mysteries of our universe.”

Based on the waves detected, the LIGO Scientific Collaboration (LSC) and Virgo collaboration were able to determine the type of event, as well as the mass of the objects involved. According to their study, the event was triggered by the merger of two black holes – which were 31 and 25 Solar Masses, respectively. The event took place about 1.8 billion light years from Earth, and resulted in the formation of a spinning black hole with about 53 Solar Masses.

What this means is that about three Solar Masses were converted into gravitational-wave energy during the merger, which was then detected by LIGO and Virgo. While impressive on its own, this latest detection is merely a taste of what gravitational wave detectors like the LIGO and Virgo collaborations can do now that they have entered their advanced stages, and into cooperation with each other.

Both Advanced LIGO and Advanced Virgo are second-generation gravitational-wave detectors that have taken over from previous ones. The LIGO facilities, which were conceived, built, and are operated by Caltech and MIT, collected data unsuccessfully between 2002 and 2010. However, as of September of 2015, Advanced LIGO went online and began conducting two observing runs – O1 and O2.

Meanwhile, the original Virgo detector conducted observations between 2003 and October of 2011, once again without success. By February of 2017, the integration of the Advanced Virgo detector began, and the instruments went online by the following April. In 2007, Virgo and LIGO also partnered to share and jointly analyze the data recorded by their respective detectors.

In August of 2017, the Virgo detector joined the O2 run, and the first-ever simultaneous detection took place on August 14th, with data being gathered by all three LIGO and Virgo instruments. As LSC spokesperson David Shoemaker – a researcher with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) – indicated, this detection is just the first of many anticipated events.

“This is just the beginning of observations with the network enabled by Virgo and LIGO working together,” he said. “With the next observing run planned for fall 2018, we can expect such detections weekly or even more often.”

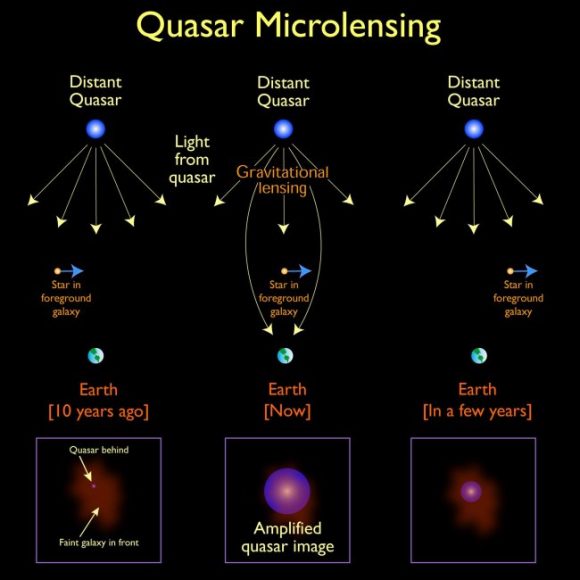

Not only will this mean that scientists have a better shot of detecting future events, but they will also be able to pinpoint them with far greater accuracy. In fact, the transition from a two- to a three-detector network is expected to increase the likelihood of pinpointing the source of GW170814 by a factory of 20. The sky region for GW170814 is just 60 square degrees – more than 10 times smaller than with data from LIGO’s interferometers alone.

In addition, the accuracy with which the distance to the source is measured has also benefited from this partnership. As Laura Cadonati, a Georgia Tech professor and the deputy spokesperson of the LSC, explained:

“This increased precision will allow the entire astrophysical community to eventually make even more exciting discoveries, including multi-messenger observations. A smaller search area enables follow-up observations with telescopes and satellites for cosmic events that produce gravitational waves and emissions of light, such as the collision of neutron stars.”

In the end, bringing more detectors into the gravitational-wave network will also allow for more detailed test’s of Einstein’s theory of General Relativity. Caltech’s David H. Reitze, the executive director of the LIGO Laboratory, also praised the new partnership and what it will allow for.

“With this first joint detection by the Advanced LIGO and Virgo detectors, we have taken one step further into the gravitational-wave cosmos,” he said. “Virgo brings a powerful new capability to detect and better locate gravitational-wave sources, one that will undoubtedly lead to exciting and unanticipated results in the future.”

The study of gravitational waves is a testament to the growing capability of the world’s science teams and the science of interferometry. For decades, the existence of gravitational waves was merely a theory; and by the turn of the century, all attempts to detect them had yielded nothing. But in just the past eighteen months, multiple detections have been made, and dozens more are expected in the coming years.

What’s more, thanks to the new global network and the improved instruments and methods, these events are sure to tell us volumes about our Universe and the physics that govern it.

Further Reading: NSF, LIGO-Caltech, LIGO DD