We’ve spent a few articles on Universe Today talking about just how difficult it’s going to be to travel to other stars. Sending tiny unmanned probes across the vast gulfs between stars is still mostly science fiction. But to send humans on that journey? That’s just a level of technology beyond comprehension.

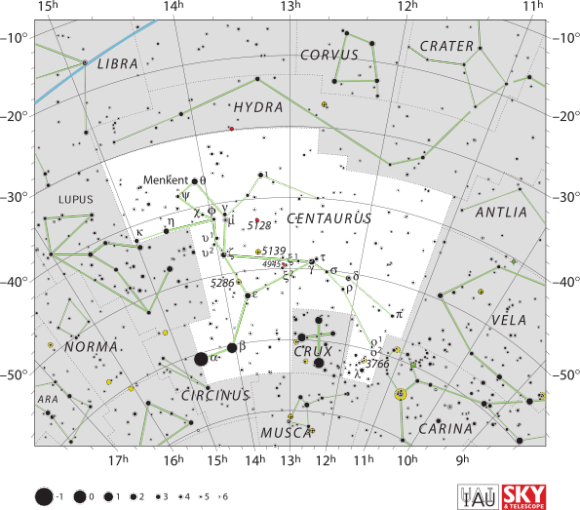

For example, the nearest star is Proxima Centauri, located a mere 4.25 light years away. Just for comparison, the Voyager spacecraft, the most distant human objects ever built by humans, would need about 50,000 years to make that journey.

I don’t know about you, but I don’t anticipate living 50,000 years. No, we’re going to want to make the journey more quickly. But the problem, of course, is that going more quickly requires more energy, new forms of propulsion we’ve only starting to dream up. And if you go too quickly, mere grains of dust floating through space become incredibly dangerous.

Based on our current technology, it’s more likely that we’re going to have to take our time getting to another star.

And if you’re going to go the slower route, you’ve got a couple of options. Create a generational ship, so that successive generations of humans are born, live out their lives, and then die during the hundreds or even thousands of year long journey to another star.

Imagine you’re one of the people destined to live and die, never reaching your destination. Especially when you look out your window and watch a warp ship zip past with all those happy tourists headed to Proxima Centauri, who were start enough to wait for warp drives to be invented.

No, you want to sleep for the journey to the nearest star, so that when you get there, it’s like no time passed. And even if warp drive did get invented while you were asleep, you didn’t have to see their smug tourist faces as they zipped past.

Is human hibernation possible? Can we do it long enough to survive a long-duration spaceflight journey and wake up again on the other side?

Before I get into this, we’re just going to have to assume that we never merge with our robot overlords, upload ourselves into the singularity, and effortlessly travel through space with our cybernetic bodies.

For some reason, that whole singularity thing never worked out, or the robots went on strike and refused to do our space exploration for us any more. And so, the job of space travel fell to us, the fragile, 80-year lifespanned mammals. Exploring the worlds within the Solar System and out to other stars, spreading humanity into the cosmos.

Come on, we know it’ll totally be the robots. But that’s not what the science fiction tells us, so let’s dig into it.

We see animals, and especially mammals hibernating all the time in nature. In order to be able survive over a harsh winter, animals are capable of slowing their heart rate down to just a few beats a minute. They don’t need to eat or drink, surviving on their fat stores for months at a time until food returns.

It’s not just bears and rodents that can do it, by the way, there are actually a couple of primates, including the fat-tailed dwarf lemur from Madagascar. That’s not too far away on the old family tree, so there might be hope for human hibernation after all.

In fact, medicine is already playing around with human hibernation to improve people’s chances to survive heart attacks and strokes. The current state of this technology is really promising.

They use a technique called therapeutic hypothermia, which lowers the temperature of a person by a few degrees. They can use ice packs or coolers, and doctors have even tried pumping a cooled saline solution through the circulatory system. With the lowered temperature, a human’s metabolism decreases and they fall unconscious into a torpor.

But the trick is to not make them so unconscious that they die. It’s a fine line.

The results have been pretty amazing. People have been kept in this torpor state for up to 14 days, going through multiple cycles.

The therapeutic use of this torpor is still under research, and doctors are learning if it’s helpful for people with heart attacks, strokes or even the progression of diseases like cancer. They’re also trying to figure out if there are any downsides, but so far, there don’t seem to be any long-term problems with putting someone in this torpor state.

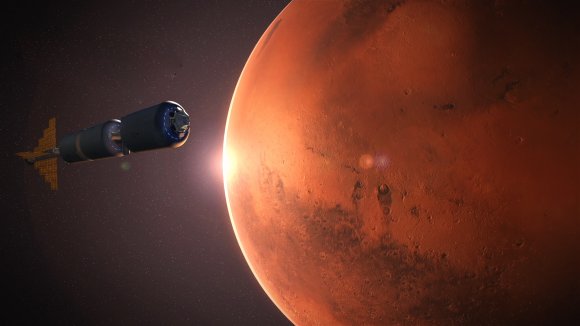

A few years ago, SpaceWorks Enterprises delivered a report to NASA on how they could use this therapeutic hypothermia for long duration spaceflight within the Solar System.

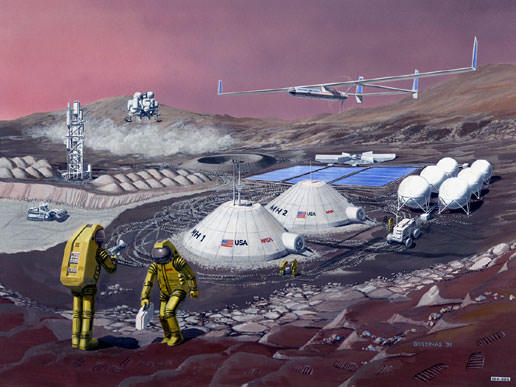

Currently, a trip to Mars takes about 6-9 months. And during that time, the human passengers are going to be using up precious air, water and food. But in this torpor state, SpaceWorks estimates that the crew will a reduction in their metabolic rate of 50 to 70%. Less metabolism, less resources needed. Less cargo that needs to be sent to Mars.

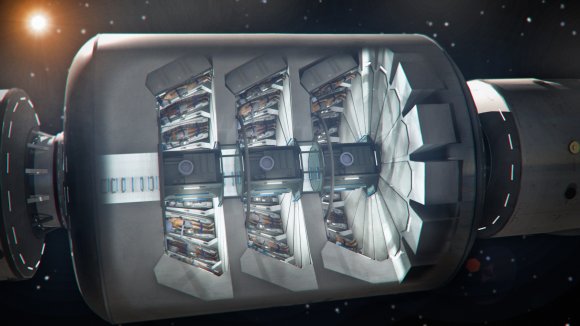

The astronauts wouldn’t need to move around, so you could keep them nice and snug in little pods for the journey. And they wouldn’t get into fights with each other, after 6-9 months of nothing but day after day of spaceflight.

We know that weightlessness has a negative effect on the body, like loss of bone mass and atrophy of muscles. Normally astronauts exercise for hours every day to counteract the negative effects of the reduced gravity. But SpaceWorks thinks it would be more effective to just put the astronauts into a rotating module and let artificial gravity do the work of maintaining their conditioning.

They envision a module that’s 4 metres high and 8 metres wide. If you spin the habitat at 20 revolutions per minute, you give the crew the equivalent of Earth gravity. Go at only 11.8 RPM and it’ll feel like Mars gravity. Down to 7.8 and it’s lunar gravity.

Normally spinning that fast in a habitat that small would be extremely uncomfortable as the crew would experience different forces at different parts of their body. But remember, they’ll be in a state of torpor, so they really won’t care.

Current plans for sending colonists to Mars would require 40 ton habitats to support 6 people on the trip. But according to SpaceWorks, you could reduce the weight down to 15 tons if you just let them sleep their way through the journey. And the savings get even better with more astronauts.

The crew probably wouldn’t all sleep for the entire journey. Instead, they’d sleep in shifts for a few weeks. Taking turns to wake up, check on the status of the spacecraft and crew before returning to their cryosleep caskets.

What’s the status of this now? NASA funded stage 1 of the SpaceWorks proposal, and in July, 2016 NASA moved forward with Phase 2 of the project, which will further investigate this technique for Mars missions, and how it could be used even farther out in the Solar System.

Elon Musk should be interested in seeing their designs for a 100-person module for sending colonists to Mars.

In addition, the European Space Agency has also been investigating human hibernation, and a possible way to enable long-duration spaceflight. They have plans to test out the technology on various non-hibernating mammals, like pigs. If their results are positive, we might see the Europeans pushing this technology forward.

Can we go further, putting people to sleep for decades and maybe even the centuries it would take to travel between the stars?

Right now, the answer is no. We don’t have any technology at our disposal that could do this. We know that microbial life can be frozen for hundreds of years. Right now there are parts of Siberia unfreezing after centuries of permafrost, awakening ancient microbes, viruses, plants and even animals. But nothing on the scale of human beings.

When humans freeze, ice crystals form in our cells, rupturing them permanently. There is one line of research that offers some hope: cryogenics. This process replaces the fluids of the human body with an antifreeze agent which doesn’t form the same destructive crystals.

Scientists have successfully frozen and then unfrozen 50-milliliters (almost a quarter cup) of tissue without any damage.

In the next few years, we’ll probably see this technology expanded to preserving organs for transplant, and eventually entire bodies, and maybe even humans. Then this science fiction idea might actually turn into reality. We’ll finally be able to sleep our way between the stars.