During the 18th century, famed French astronomer Charles Messier noted the presence of several “nebulous objects” in the night sky. Having originally mistaken them for comets, he began compiling a list of them so that others would not make the same mistake he did. In time, this list (known as the Messier Catalog) would come to include 100 of the most fabulous objects in the night sky.

One of these is the Beehive Cluster (aka. Messier 44, or Praesepe), an open star cluster located in the the Cancer constellation. In addition to containing a larger population of stars than most clusters in its vicinity, it is also one of the nearest open clusters to the Solar System – at a distance of 577 light years (177 parsecs). As such, astronomers have been aware of it since Classical Antiquity.

Description:

According to ancient lore, this group of stars (often called the Praesepe) foretold a coming storm if it was not visible in otherwise clear skies. Of course, this came from a time when combating light pollution meant asking your neighbors to dim their candles. But, once you learn where it’s at, it can be spotted unaided even from suburban settings. Hipparchus called it the “Little Cloud,” but not until the early 1600s was its stellar nature revealed.

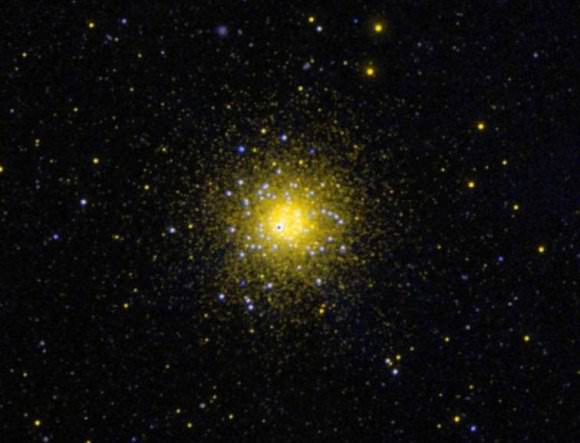

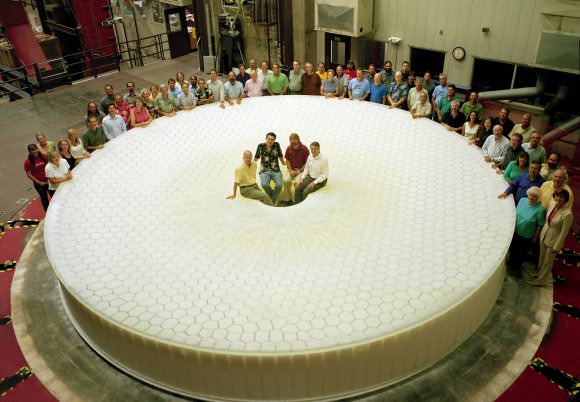

Believed to be about 550 light-years away, this awesome cluster consists of hundreds of members – with at least four orange giants and five white dwarfs. M44’s age is similar to that of the Pleiades, and it is believed that both clusters have a common origin. Although you won’t see any nebulosity in the Beehive, even the very smallest of binoculars will reveal a swarm of bright stars and large telescopes can resolve down to 350 faint stars.

Messier 44 is the nearest open cluster of its type to our Solar System, and it contains a larger star population than most other nearby clusters. Under dark skies the Beehive Cluster looks like a nebulous object to the unaided eye; thus it has been known since ancient times. The classical astronomer Ptolemy called it “the nebulous mass in the heart of Cancer,” and it was among the first objects that Galileo studied with his telescope.

The cluster’s age and proper motion coincide with those of the Hyades stellar association, suggesting that both share a similar origin. Both clusters also contain red giants and white dwarfs, which represent later stages of stellar evolution, along with main sequence stars of spectral classes A, F, G, K, and M. So far, eleven white dwarfs have been identified, representing the final evolutionary phase of the cluster’s most massive stars, which originally belonged to spectral type B. Brown dwarfs, however, are extremely rare in this cluster, probably because they have been lost by tidal stripping from the halo.

Messier 44 is home to 5 red giant stars and a handful of white dwarf stars. But, M44 also contains one peculiar blue star. Among its members, there is the eclipsing binary TX Cancri, the metal line star Epsilon Cancri, and several Delta Scuti variables of magnitudes 7-8, in an early post-main-sequence state. And in all those stars, there’s a lot of other peculiarities to be found!

As Sergei M. Andrievsky indicated in a 1998 study:

“We present the results of a spectroscopic study of four blue stragglers from old galactic open cluster NGC 2632 (Praesepe). The LTE analysis based on Kurucz’s atmosphere models and synthetic spectra technique has shown that three stars, including the hottest star of the cluster HD73666, possess an uniform chemical composition: they show a solar-like abundance (or slight overabundance) of iron and an apparent deficiency of oxygen and silicon. Two stars exhibit a remarkable barium overabundance. The chemical composition of their atmospheres is typical for Am stars. One star of our sample does not share such uniform elemental distribution, being generally deficient in metals.”

But is there more hiding in there? Perhaps the kind of stuff that could eventually make planets? According to a 2009 study done by A. Gaspar (et al), this was certainly thought to the be the case:

“Mid-IR excesses indicating debris disks are found for one early-type and for three solar-type stars. The incidence of excesses is in agreement with the decay trend of debris disks as a function of age observed for other cluster and field stars. We show that solar-type stars lose their debris disk 24 um excesses on a shorter timescale than early-type stars. Simplistic Monte Carlo models suggest that, during the first Gyr of their evolution, up to 15%-30% of solar-type stars might undergo an orbital realignment of giant planets such as the one thought to have led to the Late Heavy Bombardment, if the length of the bombardment episode is similar to the one thought to have happened in our solar system.”

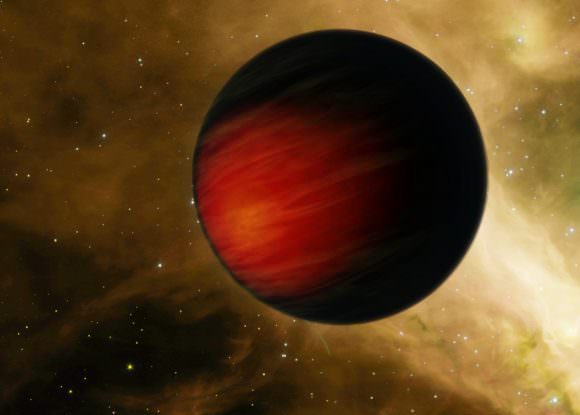

In September of 2012, two planets were confirmed to be orbiting around two separate stars in the Beehive Cluster. The finding was significant since the stars were similar to Earth’s Sun, and this was the first instance where exoplanets were found orbiting a Sun-like star within a stellar cluster. These planets were designated as Pr0201b and Pr0211b, both of which are “Hot Jupiters” (i.e. gas giants that orbit close to their stars). In 2016, additional observations showed that the Pr0211 system actually has two planets, the second one being Pr0211-c.

History of Observation:

This beautiful, nearby star cluster has been known since ancient times and played wonderful roles in mythology. Aratos mentioned this object as “Little Mist” as far back as 260 BC, and Hipparchus included this object in his star catalog and called it “Little Cloud” or “Cloudy Star” in 130 BC. Ptolemy mentions it as one of seven “nebulae” he noted in his Almagest, and describes it as “The Nebulous Mass in the Breast (of Cancer)”.

According to Burnham, it appeared on Johann Bayer’s chart (about 1600 AD) as “Nubilum” (“Cloudy” Object). It was even resolved by Galileo in 1609 who said: “The nebula called Praesepe contains not one star only but a mass of more than 40 small stars. We have noted 36 besides the Aselli (Gamma and Delta Cancri).”

Messier 44 was partly resolved by Orion nebula’s discoverer, Peiresc, in 1611, who said, “Nebula was seen in the vicinity of Jupiter to the east. in which more than 15 stars have been counted.” and added to Hevelius’ catalog as number 291. De Cheseaux charted it as his number 11 and Bode as his number 20. Small wonder Messier felt the need to add his own numbers to it as well when he recorded:

“At simple view [with the naked eye], one sees in Cancer a considerable nebulosity: this is nothing but a cluster of many stars which one distinguishes very well with the help of telescopes, and these stars are mixed up at simple view [to the unaided eye] because of their great proximity. The position in right ascension of one of the stars, which Flamsteed has designated with the letter c, reduced to March 4, 1769, should be 126d 50′ 30″, for its right ascension, and 20d 31′ 38″ for its northern declination. This position is deduced from that which Flamsteed has given in his catalog.”

While Sir William Herschel would ignore it and Caroline Herschel would only write that she “observed it”, John Herschel would go on to give it an NGC designation and Admiral Smyth would sing its poetic praises. Is it possible that watching this star cluster could help fortell the weather? If you believe the words of Aratos, it just might.

“Watch, too, the Manger. Like a faint mist in the North it plays the guide beneath Cancer. Around it are borne two faintly gleaming stars, not far apart nor very near but distant to the view a cubit.s length, one on the North, while the other looks towards the South. They are called the Asses [in the constellation Cancer], and between them is the Manger. On a sudden, when all the sky is clear, the Manger wholly disappears, while the stars that go on either side seem nearer drawn to one another: not slight then is the storm with which the fields are deluged. If the Manger darken and both stars remain unaltered, they herald rain. But if the Ass to the North of the Manger shine feebly through a faint mist, while the Southern Ass is gleaming bright, expect wind from the South: but if in turn the Southern Ass is cloudy and the Northern bright, watch for the North wind.”

And watch for a swarm of incredible starlight!

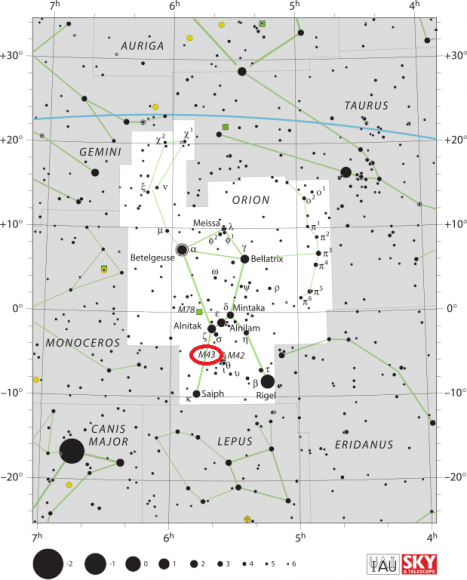

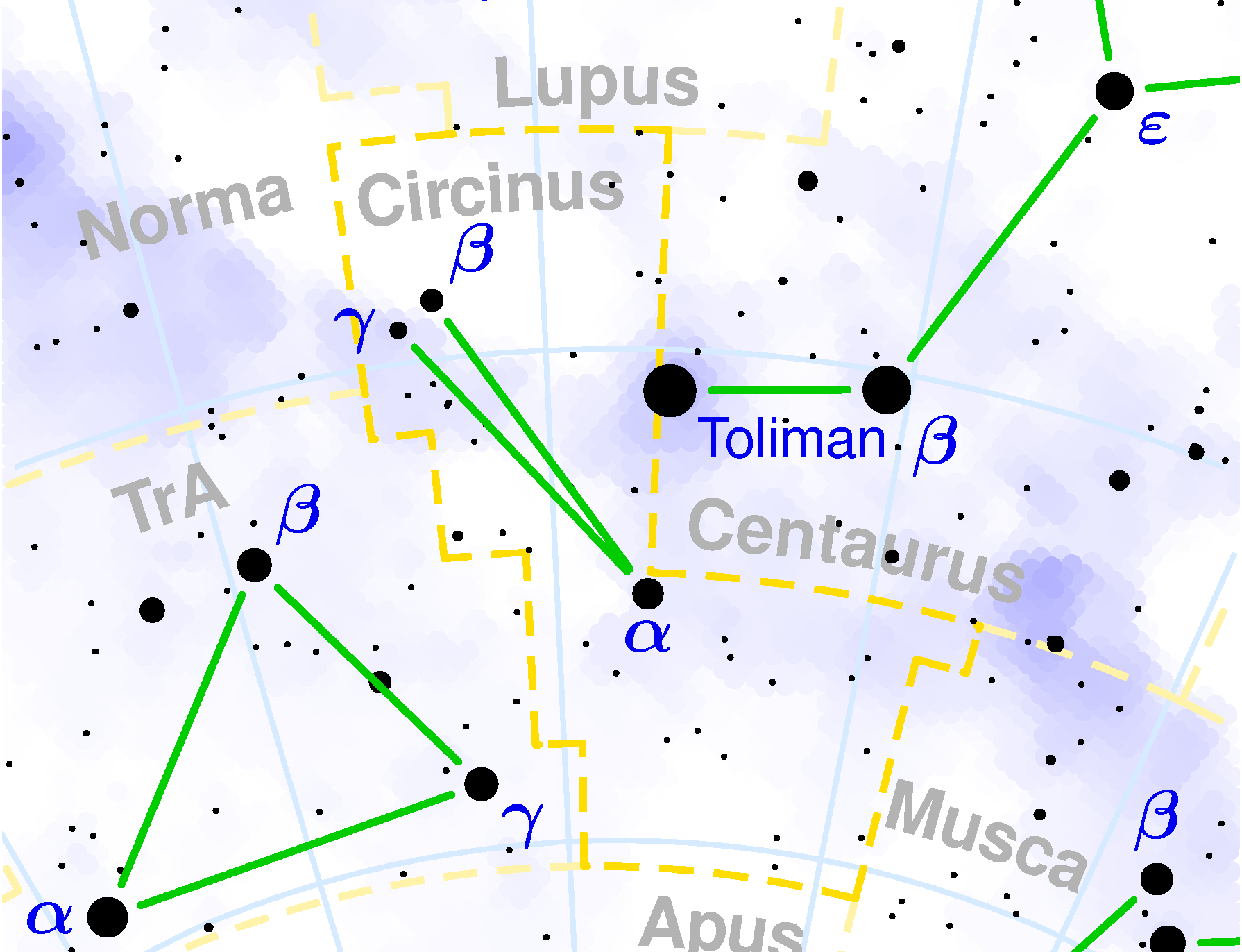

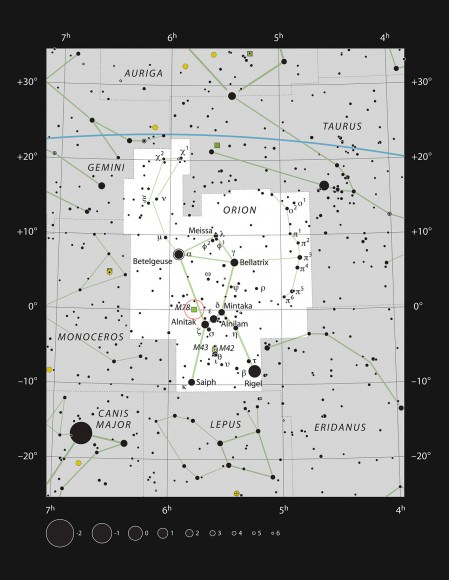

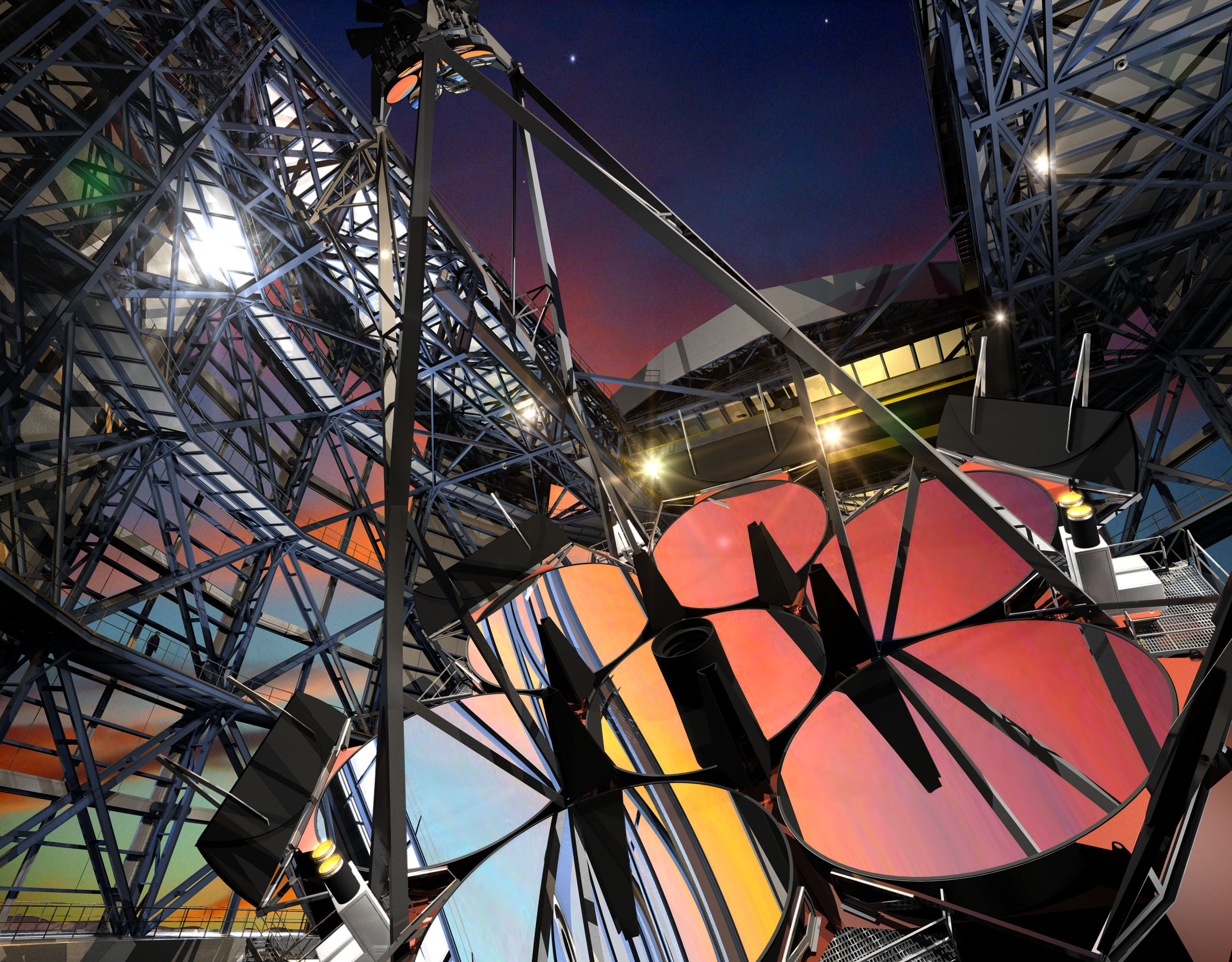

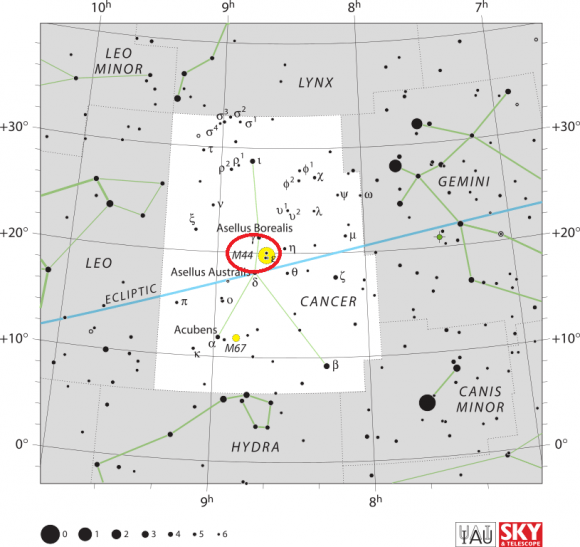

Locating Messier 44:

Messier 44 is so bright that it easily shows to the unaided eye as a nebulous patch just above the conjunction of the faint, upside down “Y” asterism of the Cancer constellation. However, not everyone lives where dark skies are a rule – so try using both Pollux and Procyon to form the base of an imaginary triangle. Now aim your binoculars or finderscope near the point of the apex to discover M44 – the Beehive.

Since Messier 44 is about a degree and a half in diameter, it will require that you use your lowest magnification eyepiece in a telescope, and it is very well suited to binoculars of all sizes. Because its major stars are also quite bright, it stands up to urban sky and moonlight conditions, but many more stars are revealed with higher magnification and darker skies. Because M44 is very near the ecliptic plane, you’ll often find a planet or the Moon mixing it up with the stars!

Object Name: Messier 44

Alternative Designations: M44, NGC 2632, Beehive Cluster, The Praesepe, The Manger

Object Type: Open Galactic Star Cluster

Constellation: Cancer

Right Ascension: 08 : 40.1 (h:m)

Declination: +19 : 59 (deg:m)

Distance: .577 (kly)

Visual Brightness: 3.7 (mag)

Apparent Dimension: 95.0 (arc min)

We have written many interesting articles about Messier Objects here at Universe Today. Here’s Tammy Plotner’s Introduction to the Messier Objects, , M1 – The Crab Nebula, M8 – The Lagoon Nebula, and David Dickison’s articles on the 2013 and 2014 Messier Marathons.

Be to sure to check out our complete Messier Catalog. And for more information, check out the SEDS Messier Database.

Sources: