Welcome back to Messier Monday! In our ongoing tribute to the great Tammy Plotner, we take a look at the Pinweel Cluster, otherwise known as Messier 36. Enjoy!

During the 18th century, famed French astronomer Charles Messier noted the presence of several “nebulous objects” in the night sky. Having originally mistaken them for comets, he began compiling a list of them so that others would not make the same mistake he did. In time, this list (known as the Messier Catalog) would come to include 100 of the most fabulous objects in the night sky.

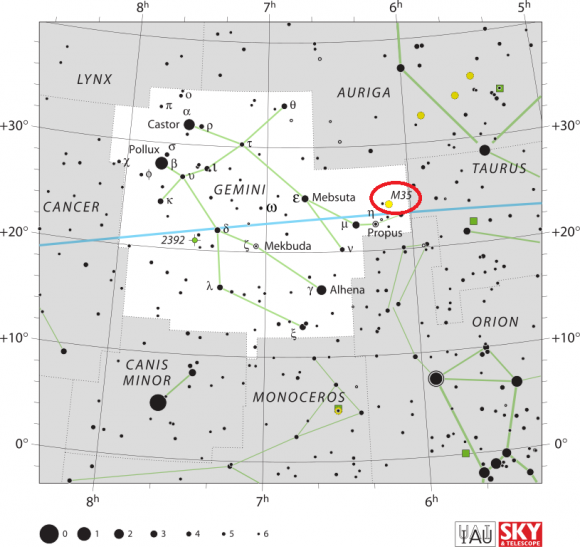

Included in this list is the open star cluster Messier 36, also known as the Pinwheel Cluster. This cluster is so-named because of its association with the Auriga constellation (aka. “the Charioteer”). Though similar in size and make-up to the Pleiades Cluster (Messier 45), the Pinwheel Cluster is actually ten times farther away from Earth – and one of the most distant of any clusters catalogued by Messier.

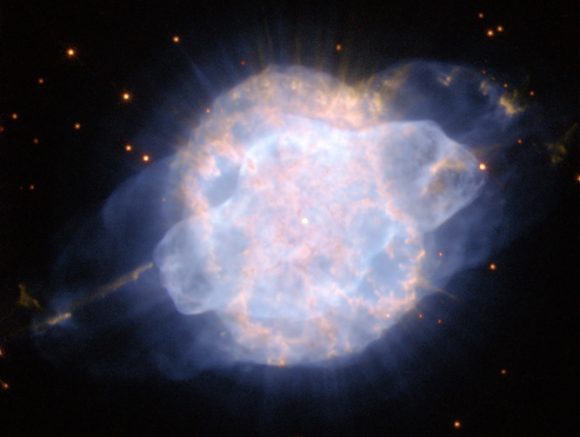

What You Are Looking At:

Located a little more than 4000 light years from our solar system, this group of about 60 stars spans across about 14 light years of space. As you are studying it, you’ll notice one star which seems brighter than the rest… With good reason! Its a spectral type B2 and about 360 more luminous than our Sun. Many of the cluster members here are also B-type stars and rapid rotators.

This means that 25 million year old Messier 36 shares a lot in common with another nearby star cluster, the Pleiades. By taking a deep look at young clusters with stars of varying ages, astronomers are able to how long circumstellar disks may last – giving us a clue as to whether or not planet-forming stars may lay within them.

As Karl E. Haisch, Jr. (et al), wrote in a 2001 study “Disk Frequencies and Lifetimes in Young Clusters“:

“We have completed the first systematic and homogeneous survey for circumstellar disks in a sample of young clusters that both span a significant range in age and contain statistically significant numbers of stars whose masses span nearly the entire stellar mass spectrum. Analysis of the combined survey indicates that the cluster disk fraction is initially very high and rapidly decreases with increasing cluster age, such that one-half the stars within the clusters lose their disks in 3 million years. Moreover, these observations yield an overall disk lifetime of ~6 million years in the surveyed cluster sample. This is the timescale for essentially all the stars in a cluster to lose their disks. This should set a meaningful constraint for the planet-building timescale in stellar clusters.”

ut, can M36 hold surprises? You betcha’. As Bo Reipurth stated in a 2008 study titled “Star Formation and Molecular Clouds towards the Galactic Anti-Center“:

“The open cluster M36 (NGC 1960), which apparently forms the center of the Aur OB1 association, has been the subject of numerous analyses, and of these the earliest studies are today of historical interest only. NGC 1960 has recently attracted attention as the most likely origin of a massive OB star that exploded about 40,000 yr ago, creating the supernova remnant Simeis 147, an old supernova remnant listed in the catalog compiled at Simeiz by Gaze & Shajn (1952). A pulsar, PSR J0538+2817, has been found near the center of Simeis 147.”

And the search for planet-building stars within M36 hasn’t stopped yet. The Spitzer Space telescope will also be investigating it, thanks to a proposal made by George Rieke:

“We propose a deep IRAC/MIPS survey of NGC 1960, a ~20 Myr-old massive cluster unexplored in the mid infrared. This cluster is at a key stage in terrestrial planet formation. Our survey will likely detect infrared excess emission from debris disks and transition disks from ~ 100 intermediate-mass (1-3 solar mass) stars. Together with ground-based photometry/spectroscopy of this cluster, proposed observations of 10 Myr-old NGC 6871, scheduled cycle 4 observations of the massive 13 Myr old clusters h and chi Persei, and existing data on NGC 2547 at 30 Myr, this survey will yield robust constraints on the frequency of debris/transition disks as a function of spectral type, age, and cluster environment at a critical age range for planet formation. This survey will provide a benchmark study of the observable signatures of terrestrial planet formation that will inform James Webb Space Telescope observations of planet-forming disks a decade from now.”

History of Observation:

The presence of this awesome star cluster was first recorded by Giovanni Batista Hodierna before 1654 and re-discovered by Le Gentil in 1749. However, it was Charles Messier who took the time to carefully record its position for future generations:

“In the night of September 2 to 3, 1764, I have determined the position of a star cluster in Auriga, near the star Phi of that constellation. With an ordinary refractor of 3 feet and a half, one has difficulty to distinguish these small stars; but when employing a stronger instrument, one sees them very well; they don’t contain between them any nebulosity: their extension is about 9 minutes of arc. I have compared the middle of this cluster with the star Phi Aurigae, and I have determined its position; its right ascension was 80d 11′ 42″, and its declination 34d 8′ 6″ north.”

It would be observed again by Caroline, William and John Herschel who would be the first to note the double star in M36’s center. Although none of their notes are particularly glowing on this awesome star cluster, Admiral Symth does come to the historic rescue!

“A neat double star in a splendid cluster, on the robe below the Waggoner’s left thigh, and near the centre of the Galaxy stream. A [mag] 8 and B 9, both white; in a rich though open splash of stars from the 8th to the 14th magnitudes, with numerous outliers, like the device of a star whose rays are formed by very small stars. This object was registered by M. [Messier] in 1764; and the double star, as H. [John Herschel] remarks, is admirably placed, for future astronomers to ascertain whether there be internal motion in clusters. A line carried from the central star in Orion’s belt, through Zeta Tauri, and continued about 13deg beyond, will reach the cluster, following Phi Aurigae by about two degrees.”

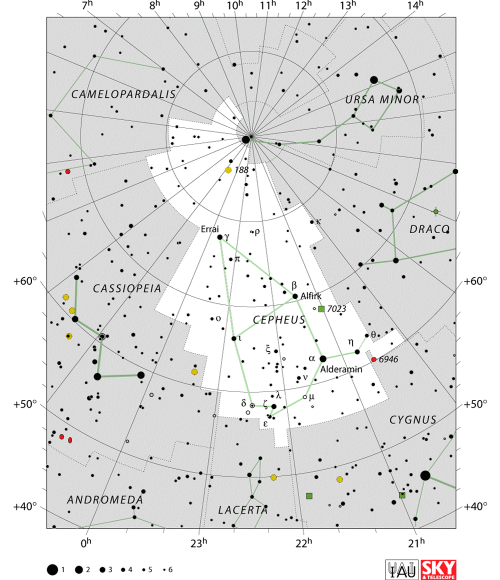

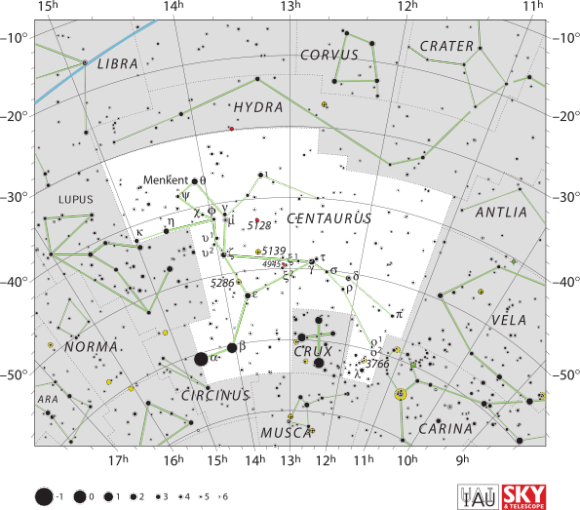

Locating Messier 36:

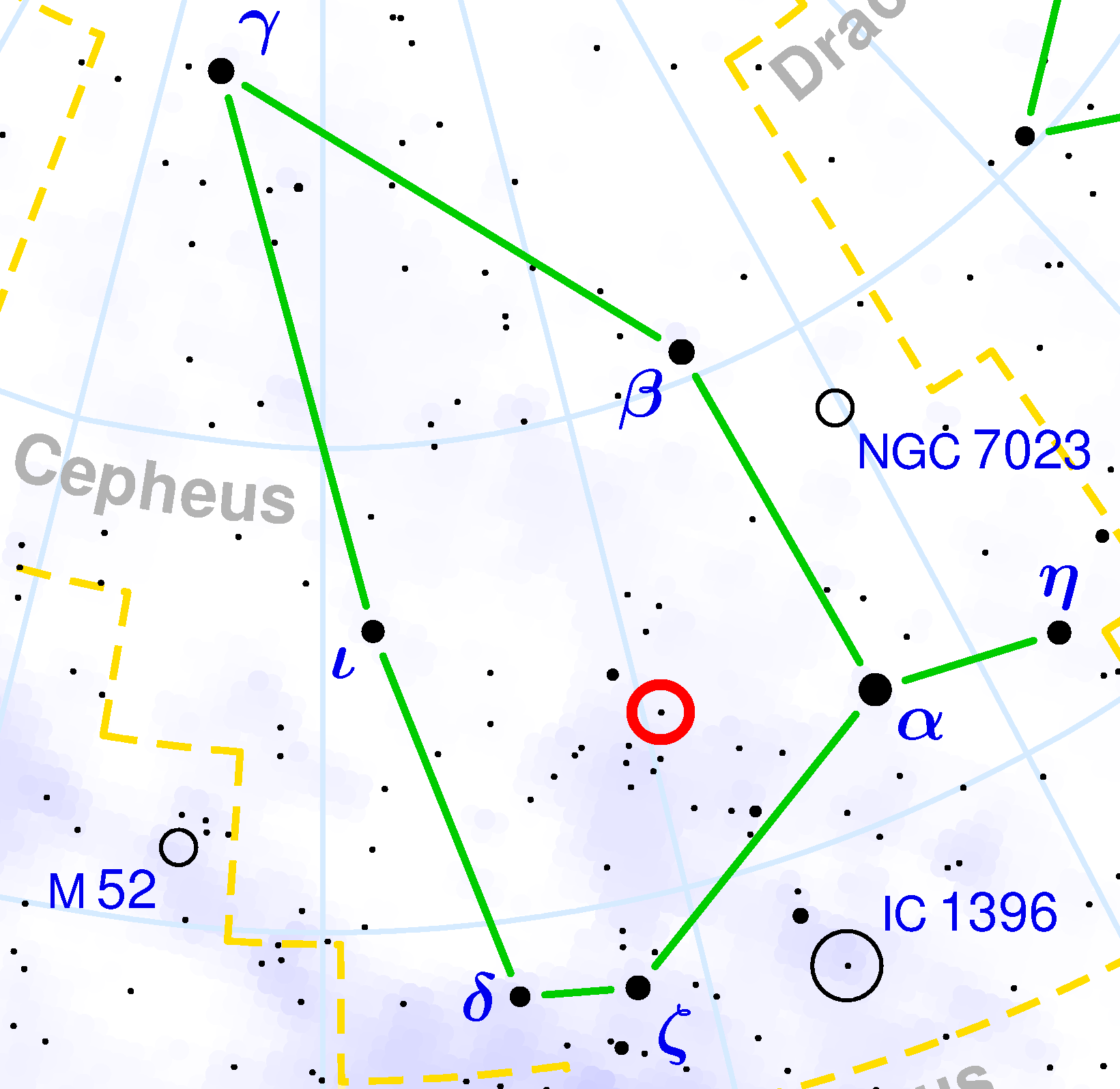

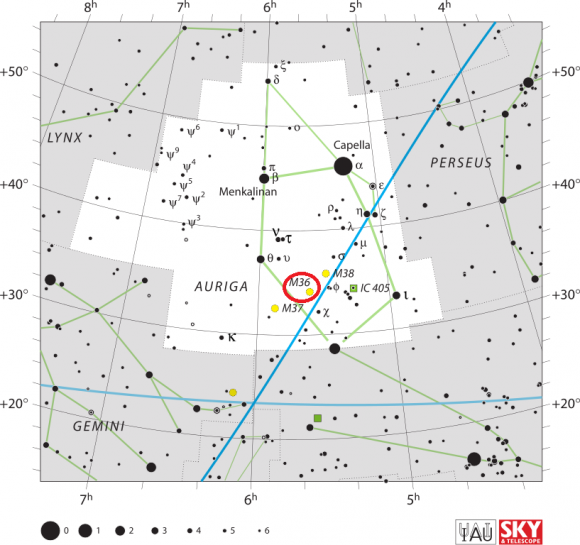

Locating Messier 36 is relatively easy once you understand the constellation of Auriga. Looking roughly like a pentagon in shape, start by identifying the brightest of these stars – Capella. Due south of it is the second brightest star which shares its border with Beta Tauri, El Nath. By aiming binoculars at El Nath, go north about 1/3 the distance between the two and enjoy all the stars!

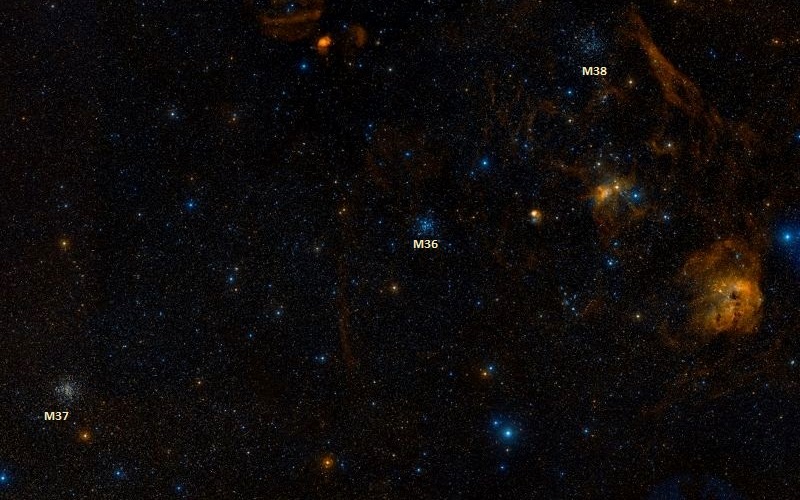

You will note two very conspicuous clusters of stars in this area, and so did Le Gentil in 1749. Binoculars will reveal the pair in the same field, as will telescopes using lowest power. The dimmest of these is the M38, and will appear vaguely cruciform in shape. At roughly 4200 light years away, larger aperture will be needed to resolve the 100 or so fainter members. About 2 1/2 degrees to the southeast (about a finger width) you will see the much brighter M36.

More easily resolved in binoculars and small scopes, this “jewel box” galactic cluster is quite young and about 100 light years closer. If you continue roughly on the same trajectory about another 4 degrees southeast you will find open cluster M37. This galactic cluster will appear almost nebula-like to binoculars and very small telescopes – but comes to perfect resolution with larger instruments.

While all three open star clusters make fine choices for moonlit or light polluted skies, remember that high sky light means less faint stars which can be resolved – robbing each cluster of some of its beauty. Messier 36 is intermediate brightness of the trio and you’ll quite enjoy its “X” shape and many pairings of stars!

Has the central double changed with time? Why not observe for yourself and see!

Object Name: Messier 36

Alternative Designations: M36, NGC 1960, Pinwheel Cluster

Object Type: Galactic Open Star Cluster

Constellation: Auriga

Right Ascension: 05 : 36.1 (h:m)

Declination: +34 : 08 (deg:m)

Distance: 4.1 (kly)

Visual Brightness: 6.3 (mag)

Apparent Dimension: 12.0 (arc min)

We have written many interesting articles about Messier Objects here at Universe Today. Here’s Tammy Plotner’s Introduction to the Messier Objects, , M1 – The Crab Nebula, M8 – The Lagoon Nebula, and David Dickison’s articles on the 2013 and 2014 Messier Marathons.

Be to sure to check out our complete Messier Catalog. And for more information, check out the SEDS Messier Database.

Sources: