Welcome back to Messier Monday! In our ongoing tribute to the great Tammy Plotner, we take a look at the globular cluster known as Messier 30. Enjoy!

During the 18th century, famed French astronomer Charles Messier noted the presence of several “nebulous objects” in the night sky. Having originally mistaken them for comets, he began compiling a list of them so that others would not make the same mistake he did. In time, this list (known as the Messier Catalog) would come to include 100 of the most fabulous objects in the night sky.

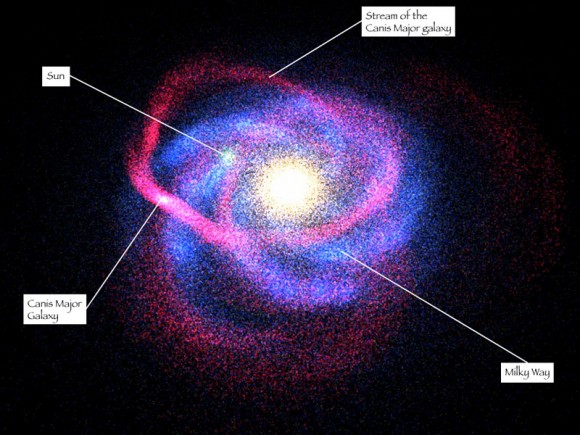

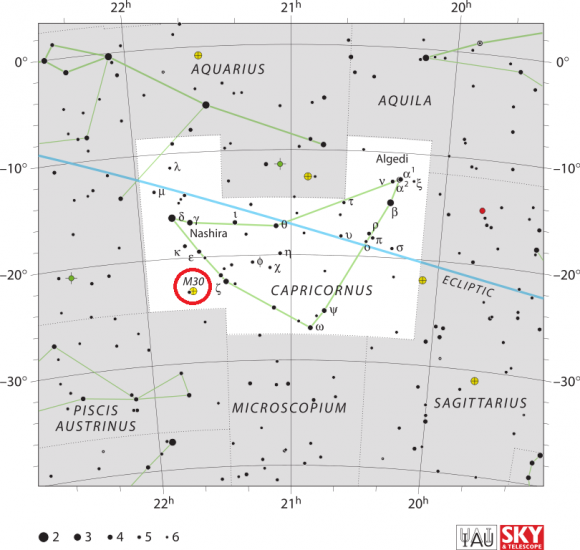

One of these objects is Messier 30, a globular cluster located in the southern constellation of Capricornus. Owing to its retrograde orbit through the inner galactic halo, it is believed that this cluster was acquired from a satellite galaxy in the past. Though it is invisible to the naked eye, this cluster can be viewed using little more than binoculars, and is most visible during the summer months.

Description:

Messier measures about 93 light years across and lies at a distance of about 26,000 light years from Earth, and approaching us at a speed of about 182 kilometers per second. While it looks harmless enough, its tidal influence covers an enormous 139 light years – far greater than its apparent size.

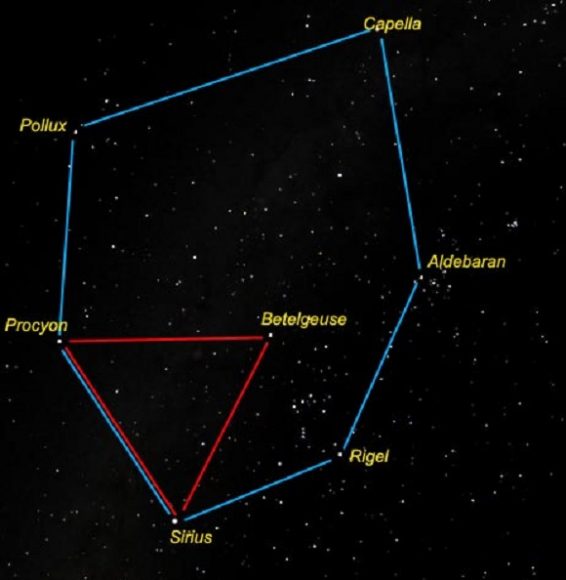

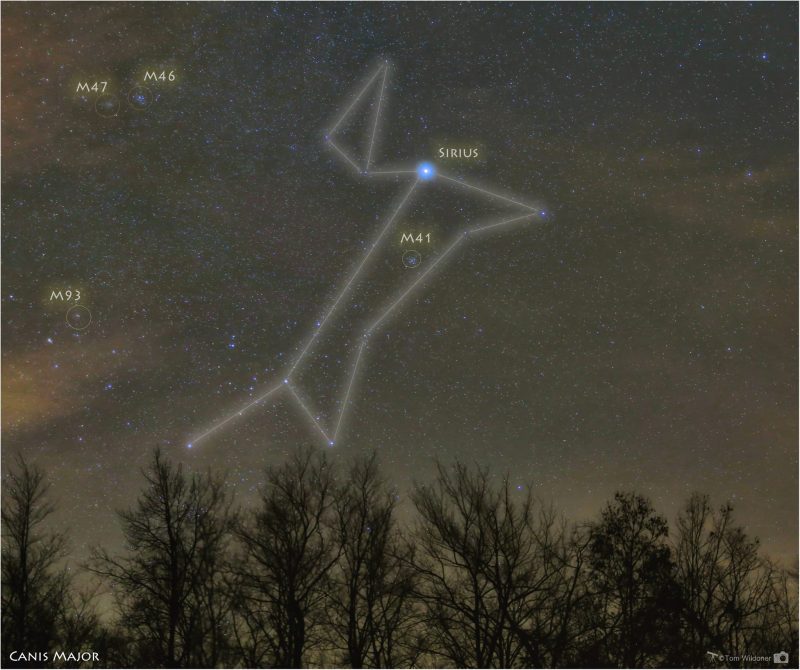

Half of its mass is so concentrated that literally thousands of stars could be compressed in an area that spans no further than the distance between our solar system and Sirius! However, inside this density only 12 variable stars have been found and very little evidence of any stellar collisions, although a dwarf nova has been recorded!

So what’s so special about this little globular? Try a collapsed core – and one that’s even been resolved by Earth-bound telescopes. According to Bruce Jones Sams III, an astrophysicists at Harvard University:

“The globular cluster NGC 7099 is a prototypical collapsed core cluster. Through a series of instrumental, observational, and theoretical observations, I have resolved its core structure using a ground based telescope. The core has a radius of 2.15 arcsec when imaged with a V band spatial resolution of 0.35 arcsec. Initial attempts at speckle imaging produced images of inadequate signal to noise and resolution. To explain these results, a new, fully general signal-to-noise model has been developed. It properly accounts for all sources of noise in a speckle observation, including aliasing of high spatial frequencies by inadequate sampling of the image plane. The model, called Full Speckle Noise (FSN), can be used to predict the outcome of any speckle imaging experiment. A new high resolution imaging technique called ACT (Atmospheric Correlation with a Template) was developed to create sharper astronomical images. ACT compensates for image motion due to atmospheric turbulence.”

Photography is an important tool for astronomers to work with – both land and space-based. By combining results, we can learn far more than just from the results of one telescope observation alone. As Justin H. Howell wrote in a 1999 study:

“It has long been known that the post-core-collapse globular cluster M30 (NGC 7099) has a bluer-inward color gradient, and recent work suggests that the central deficiency of bright red giant stars does not fully account for this gradient. This study uses Hubble Space Telescope Wide Field Planetary Camera 2 images in the F439W and F555W bands, along with ground-based CCD images with a wider field of view for normalization of the noncluster background contribution. The quoted uncertainty accounts for Poisson fluctuations in the small number of bright evolved stars that dominate the cluster light. We explore various algorithms for artificially redistributing the light of bright red giants and horizontal-branch stars uniformly across the cluster. The traditional method of redistribution in proportion to the cluster brightness profile is shown to be inaccurate. There is no significant residual color gradient in M30 after proper uniform redistribution of all bright evolved stars; thus, the color gradient in M30’s central region appears to be caused entirely by post-main-sequence stars.”

So what happens when you dig even deeper with a different type of photography? Just ask the folks from Chandra – like Phyllis M. Lugger, who wrote in her study, “Chandra X-ray Sources in the Collapsed-Core Globular Cluster M30 (NGC 7099)“:

“We report the detection of six discrete, low-luminosity X-ray sources, located within 12” of the center of the collapsed-core globular cluster M30 (NGC 7099), and a total of 13 sources within the half-mass radius, from a 50 ks Chandra ACIS-S exposure. Three sources lie within the very small upper limit of 1.9” on the core radius. The brightest of the three core sources has a blackbody-like soft X-ray spectrum, which is consistent with it being a quiescent low-mass X-ray binary (qLMXB). We have identified optical counterparts to four of the six central sources and a number of the outlying sources, using deep Hubble Space Telescope and ground-based imaging. While the two proposed counterparts that lie within the core may represent chance superpositions, the two identified central sources that lie outside of the core have X-ray and optical properties consistent with being cataclysmic variables (CVs). Two additional sources outside of the core have possible active binary counterparts.”

History of Observation:

When Charles Messier first encountered this globular cluster in 1764, he was unable to resolve individual stars, and mistakenly believed it to be a nebula. As he wrote in his notes at the time:

“In the night of August 3 to 4, 1764, I have discovered a nebula below the great tail of Capricornus, and very near the star of sixth magnitude, the 41st of that constellation, according to Flamsteed: one sees that nebula with difficulty in an ordinary [non-achromatic] refractor of 3 feet; it is round, and I have not seen any star: having examined it with a good Gregorian telescope which magnifies 104 times, it could have a diameter of 2 minutes of arc. I have compared the center with the star Zeta Capricorni, and I have determined its position in right ascension as 321d 46′ 18″, and its declination as 24d 19′ 4″ south. This nebula is marked in the chart of the famous Comet of Halley which I observed at its return in 1759.”

However, we cannot fault Messier, for his job was to hunt comets and we thank him for logging this object for further study. Perhaps the first clue to M30’s underlying potential came from Sir William Herschel, who often studied Messier’s objects, but did not report his findings formally. In his personal notes he wrote:

“A brilliant cluster, the stars of which are gradually more compressed in the middle. It is insulated, that is, none of the stars in the neighborhood are likely to be connected with it. Its diameter is from 2’40” to 3’30”. The figure is irregularly round. The stars about the centre are so much compressed as to appear to run together. Towards the north, are two rows of bright stars 4 or 5 in a line. In this accumulation of stars, we plainly see the exertion of a central clustering power, which may reside in a central mass, or, what is more probable, in the compound energy of the stars about the centre. The lines of bright stars, although by a drawing made at the time of observation, one of them seems to pass through the cluster, are probably not connected with it.”

So, as telescopes progressed and resolution improved, so did our way of thinking about what we were seeing… By Admiral Smyth’s time, things had improved even more and so had the art of understanding more:

“A fine pale white cluster, under the creature’s caudal fin, and about 20 deg west-north-west of Fomalhaut, where it precedes 41 Capricorni, a star of 5th magnitude, within a degree. This object is bright, and from the straggling streams of stars on its northern verge, has an elliptical aspect, with a central blaze; and there are but few other stars, or outliers, in the field.

“When Messier discovered this, in 1764, he remarked that it was easily seen with a 3 1/2-foot telescope, that it was a nebula, unaccompanied by any star, and that its form was circular. But in 1783 it was attacked by WH [William Herschel] with both his 20-foot Newtonians, and forthwith resolved into a brilliant cluster, with two rows pf stars, four or five in a line, which probably belong to it; and therefore he deemed it insulated. Independently of this opinion, it is situated in a blankish space, one of those chasmata which Lalande termed d’espaces vuides, wherein he could not perceive a star of the 9th magnitude in the achromatic telescope of sixty-seven millimetres aperture. By a modification of his very ingenious gauging process, Sir William considered the profundity of this cluster to be of the 344th order.

“Here are materials for thinking! What an immensity of space is indicated! Can such an arrangement be intended, as a bungling spouter of the hour insists, for a mere appendage to the speck of a world on which we dwell, to soften the darkness of its petty midnight? This is impeaching the intelligence of Infinite Wisdom and Power, in adapting such grand means to so disproportionate an end. No imagination can fill up the picture of which the visual organs afford the dim outline; and he who confidently probes the Eternal Design cannot be many removes from lunacy. It was such a consideration that made the inspired writer claim, “How unsearchable are His operations, and His ways past finding out!”

Throughout all historic observing notes, you’ll find notations like “remarkable” and even Dreyer’s famous exclamation points. Even though M30 may not be the easiest to find, nor the brightest of the Messier objects, it is still quite worthy of your time and attention!

Locating Messier 30:

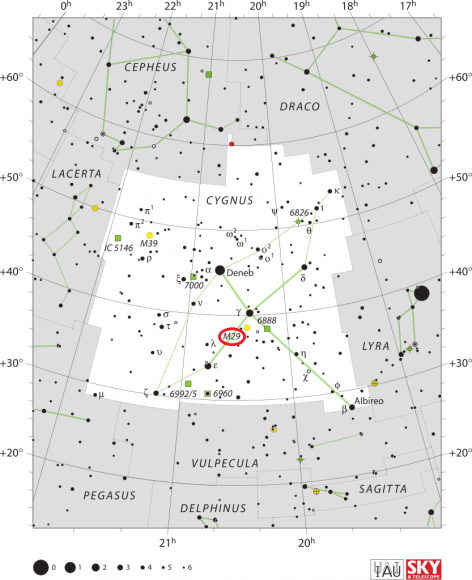

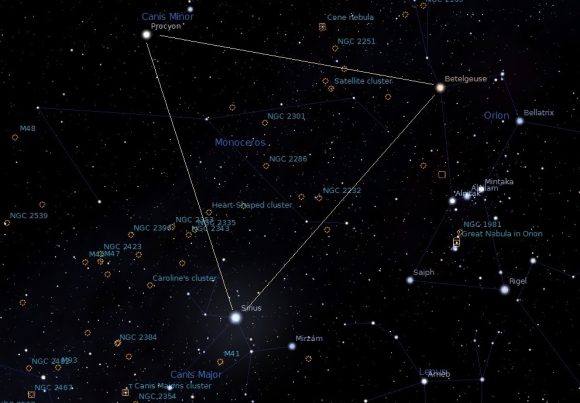

Finding M30 is not an easy task, unless you’re using a GoTo telescope. In any other case, it’s a starhop process, which must begin with identifying the the big grin-shape of the constellation of Capricornus. Once you’ve separated out this constellation, you’ll begin to notice that many of its primary asterism stars are paired – which is a good thing! The northeastern most pair are Gamma and Delta, which is where binocular-users should start.

As you move slowly south and slightly west, you’ll encounter your next wide pair – Chi and Epsilon. The next southwestern set is 36 Cap and Zeta. Now, from here you have two options! You can find Messier 30 a little more than a finger width east(ish) of Zeta (about half a binocular field)… or, you can return to Epsilon and look about one binocular field south (about 3 degrees) for star 41 which will appear just east of Messier 30 in the same field of view.

For the finderscope, star 41 is a critical giveaway to the globular cluster’s position! It won’t be visible to the unaided eye, but even a little magnification will reveal its presence. Using binoculars or a very small telescope, Messier 30 will appear as only a small, faded gray ball of light with a small star beside it. However, with telescope apertures as small as 4″ you’ll begin some resolution on this overlooked globular cluster and larger apertures will resolve it nicely.

And here are the quick facts on Messier 30 to help you get started:

Object Name: Messier 30

Alternative Designations: M30, NGC 7099

Object Type: Class V Globular Cluster

Constellation: Capricornus

Right Ascension: 21 : 40.4 (h:m)

Declination: -23 : 11 (deg:m

Distance: 26.1 (kly)

Visual Brightness: 7.2 (mag)

Apparent Dimension: 12.0 (arc min)

We have written many interesting articles about Messier Objects here at Universe Today. Here’s Tammy Plotner’s Introduction to the Messier Objects, , M1 – The Crab Nebula, M8 – The Lagoon Nebula, and David Dickison’s articles on the 2013 and 2014 Messier Marathons.

Be to sure to check out our complete Messier Catalog. And for more information, check out the SEDS Messier Database.

Sources: