Since time immemorial, people have been staring up at the Moon with awe and wonder. For as long as there has been life on this planet, the Moon has been orbiting it. And as time went on, scholars and astronomers began to observe it regularly and calculate its orbit. In so doing, they learned some rather interesting things about its behavior.

For example, the Moon has an orbital period that is the same as its rotational period. In essence, it is tidally locked to the Earth, which means that it always presents the same face to us as it orbits around our planet. And during the course of its orbit, it also appears larger and smaller in the sky, which is due to the fact it is sometimes closer than at other times.

Orbital Parameters:

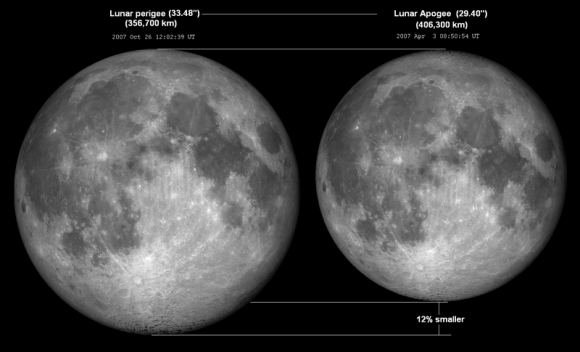

For starters, the Moon follows an elliptical path around the Earth – with an average eccentricity of 0.0549 – which means that its orbit is not perfectly circular. Its average orbital distance is 384,748 km, which ranges from 364,397 km at its closest, to 406,731 km at its most distant.

This non-circular orbit causes variations in the Moon’s angular speed and apparent size as it moves towards and away from an observer on Earth. When it’s full and at its closest point to Earth (perigee), the Moon can look over 10% bigger, and 30% brighter than when it’s at a more distant point in its orbit (apogee).

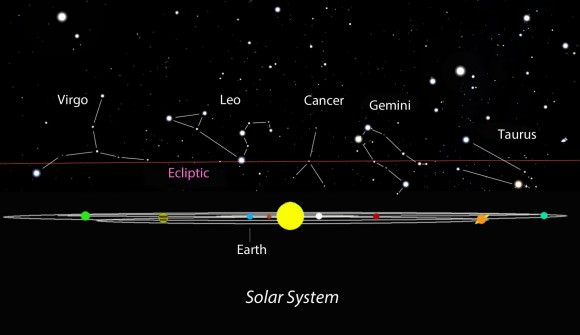

The mean inclination of the Moon’s orbit to the ecliptic plane (i.e. the apparent path of the Sun through the sky) is 5.145°. Because of this inclination, the moon is above the horizon at the North and South Pole for almost two weeks every month, even though the Sun is below the horizon for six months out of the year.

The Moon’s sidereal orbital period and rotational period are the same – 27.3 days. This phenomena, known as synchronous rotation, is what allows for the same hemisphere to be facing Earth all the time. Hence why the far side is colloquially referred to as the “Dark Side”, but this name is misleading. As the Moon orbits Earth, different parts are in sunlight or darkness at different times and neither side is permanently dark or illuminated.

Because Earth is moving as well – rotating on its axis as it orbits the Sun – the Moon appears to orbit us every 29.53 days. This is known as its synodic period, which is the amount of time it takes for the Moon to reappear in the same place in the sky. During a synodic period, the Moon will go through changes in its appearance, which are known as “phases“.

Lunar Cycle:

These changes in appearance are due to the Moon receiving more or less illumination (from our perspective). A full cycle of these phases is known as a Lunar Cycle, which comes down to the Moon’s orbit around the Earth, and our mutual orbit around the Sun. When the Sun, the Moon and Earth are perfectly lined up, the angle between the Sun and the Moon is 0-degrees.

At this point, the side of the Moon facing the Sun is fully illuminated, and the side facing the Earth is enshrouded in darkness. We call this a New Moon. After this, the phase of the Moon changes, because the angle between the Moon and the Sun is increasing from our perspective. A week after a New Moon, and the Moon and Sun are separated by 90-degrees, which effects what we will see.

And then, when the Moon and Sun are on opposite sides of the Earth, they’re at 180-degrees – which corresponds to a Full Moon. The period in which a Moon will go from a New Moon to a Full Moon and back again is also known as “Lunar Month”. One of these lasts 28 days, and encompasses what are known as “waxing” and “waning” Moons. During the former period, the Moon brightens and its angle relative to the Sun and Earth increases.

After the first week, the angle between the Moon and the Sun is 90-degrees and continues to increase to 180-degrees, when the Sun and Moon are on opposite sides of the Earth. When the Moon starts to decrease its angle again, going from 180-degrees back down to 0-degrees, astronomers say that it’s a waning moon. In other words, when the Moon is waning, it will have less and less illumination every night until it’s a New Moon.

When the Moon is no longer full, but it hasn’t reached a quarter moon – i.e. when it’s half illuminated from our perspective – we say that it’s a Waning Gibbous Moon. This is the exact reverse of a Waxing Gibbous Moon, when the Moon is increasing in brightness from a New Moon to a Full Moon.

This is followed by a Third Quarter (or last quarter) Moon. During this period, 50% of the Moon’s disc will be illuminated (left side in the northern hemisphere, and the right in the southern), which is the opposite of how it would appear during a First Quarter. These phases are often referred to as a “Half Moon”, since half the disc is illuminated at the time.

Finally, a Waning Crescent is when the Moon appears as a sliver in the night sky, where between 49–1% of one side is illuminated after a Full Moon (again, left in the northern hemisphere, right in the southern). This is the opposite of a Waxing Crescent, when 1-49% of the other wide is illuminated before it reaches a Full Moon.

Future of the Moon’s Orbit:

Currently, the Moon’s is slowly drifting away from the Earth, at a rate of about 1 to 2 cm per year. This is directly related to the fact that here on Earth, the day’s are getting longer – by a rate of 1/500th of a second every century. In fact, astronomers have estimated that roughly 620 million years ago, a day was only 21 hours long, and the Moon was between 6,200 – 12,400 km closer.

Now, the days are 24 hours long and getting longer, and the Moon is already at a average distance of 384,400 km. Eventually, the Earth and the Moon will be tidally locked to each other, so the same side of the Earth will always face the Moon, just like the same side of the Moon always presents the same face to the Earth. But this won’t happen for billions of years from now.

For as long as human beings have been staring up at the night sky, the Moon has been a part of our world. And over the course of the roughly 4.5 billion years that it has been our only natural satellite, the relationship between it and our planet has changed. As time goes on, it will continue to change; but to us, it will still be the Moon.

We’ve written many articles about the Moon for Universe Today. Here’s Interesting Facts About the Moon, What is a Moon?, Is the Moon a Planet?, What is the Diameter of the Moon?, What is the Distance to the Moon?, and Does the Moon Orbit the Sun?.

If you’d like more info on the Moon, check out NASA’s Solar System Exploration Guide on the Moon, and here’s a link to NASA’s Lunar and Planetary Science page.

We’ve also recorded an episode of Astronomy Cast all about the Moon. Listen here, Episode 113: The Moon, Part 1.

Sources:

- Wikipedia – Orbit of the Moon

- Windows to the Universe – the Moon’s Orbit

- NASA – Earth’s Moon

- Solar System Exploration – Earth’s Moon