We don’t want to scare you, but our own Milky Way is on a collision course with Andromeda, the closest spiral galaxy to our own. At some point during the next few billion years, our galaxy and Andromeda – which also happen to be the two largest galaxies in the Local Group – are going to come together, and with catastrophic consequences.

Stars will be thrown out of the galaxy, others will be destroyed as they crash into the merging supermassive black holes. And the delicate spiral structure of both galaxies will be destroyed as they become a single, giant, elliptical galaxy. But as cataclysmic as this sounds, this sort of process is actually a natural part of galactic evolution.

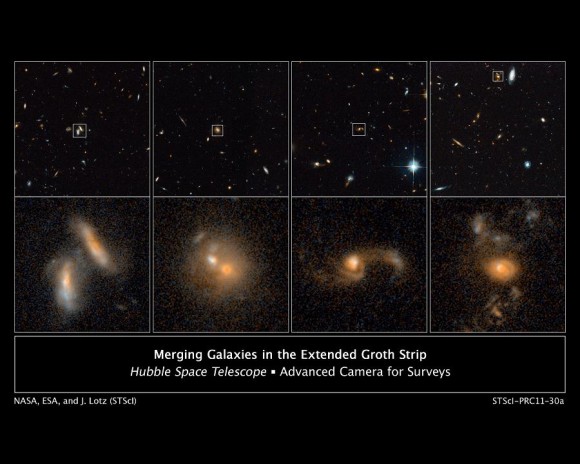

Astronomers have know about this impending collision for some time. This is based on the direction and speed of our galaxy and Andromeda’s. But more importantly, when astronomers look out into the Universe, they see galaxy collisions happening on a regular basis.

Gravitational Collisions:

Galaxies are held together by mutual gravity and orbit around a common center. Interactions between galaxies is quite common, especially between giant and satellite galaxies. This is often the result of a galaxies drifting too close to one another, to the point where the gravity of the satellite galaxy will attract one of the giant galaxy’s primary spiral arms.

In other cases, the path of the satellite galaxy may cause it to intersect with the giant galaxy. Collisions may lead to mergers, assuming that neither galaxy has enough momentum to keep going after the collision has taken place. If one of the colliding galaxies is much larger than the other, it will remain largely intact and retain its shape, while the smaller galaxy will be stripped apart and become part of the larger galaxy.

Such collisions are relatively common, and Andromeda is believed to have collided with at least one other galaxy in the past. Several dwarf galaxies (such as the Sagittarius Dwarf Spheroidal Galaxy) are currently colliding with the Milky Way and merging with it.

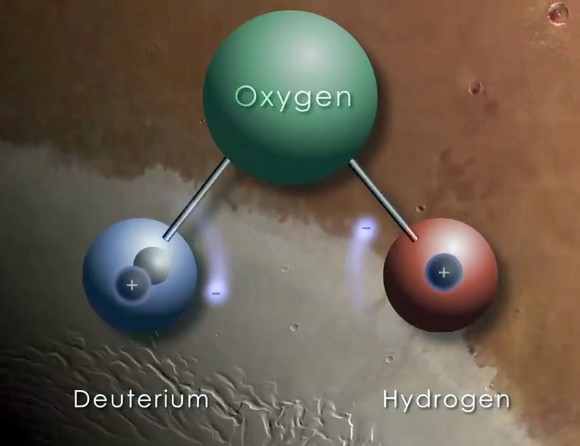

However, the word collision is a bit of a misnomer, since the extremely tenuous distribution of matter in galaxies means that actual collisions between stars or planets is extremely unlikely.

Andromeda–Milky Way Collision:

In 1929, Edwin Hubble revealed observational evidence which showed that distant galaxies were moving away from the Milky Way. This led him to create Hubble’s Law, which states that a galaxy’s distance and velocity can be determined by measuring its redshift – i.e. a phenomena where an object’s light is shifted toward the red end of the spectrum when it is moving away.

However, spectrographic measurements performed on the light coming from Andromeda showed that its light was shifted towards the blue end of the spectrum (aka. blueshift). This indicated that unlike most galaxies that have been observed since the early 20th century, Andromeda is moving towards us.

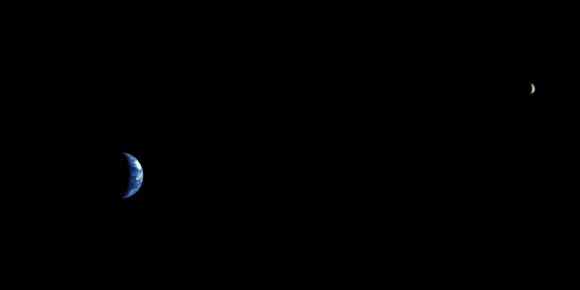

In 2012, researchers determined that a collision between the Milky Way and the Andromeda Galaxy was sure to happen, based on Hubble data that tracked the motions of Andromeda from 2002 to 2010. Based on measurements of its blueshift, it is estimated that Andromeda is approaching our galaxy at a rate of about 110 km/second (68 mi/s).

At this rate, it will likely collide with the Milky Way in around 4 billion years. These studies also suggest that M33, the Triangulum Galaxy – the third largest and brightest galaxy of the Local Group – will participate in this event as well. In all likelihood, it will end up in orbit around the Milky Way and Andromeda, then collide with the merger remnant at a later date.

Consequences:

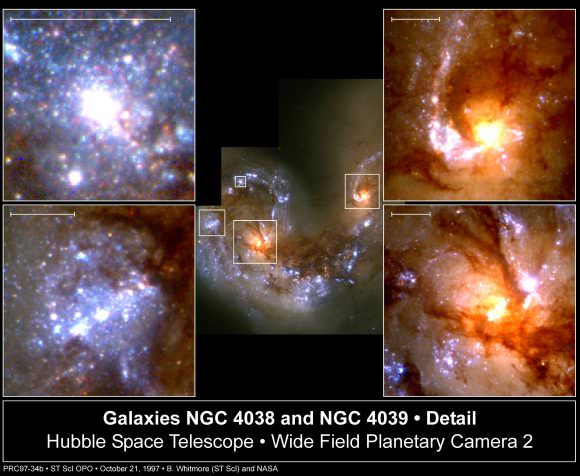

In a galaxy collision, large galaxies absorb smaller galaxies entirely, tearing them apart and incorporating their stars. But when the galaxies are similar in size – like the Milky Way and Andromeda – the close encounter destroys the spiral structure entirely. The two groups of stars eventually become a giant elliptical galaxy with no discernible spiral structure.

Such interactions can also trigger a small amount of star formation. When the galaxies collide, it causes vast clouds of hydrogen to collect and become compressed, which can trigger a series of gravitational collapses. A galaxy collision also causes a galaxy to age prematurely, since much of its gas is converted into stars.

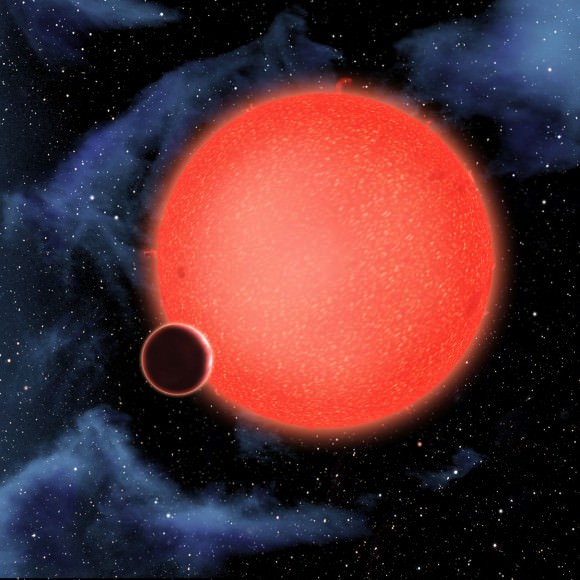

After this period of rampant star formation, galaxies run out of fuel. The youngest hottest stars detonate as supernovae, and all that’s left are the older, cooler red stars with much longer lives. This is why giant elliptical galaxies, the results of galaxy collisions, have so many old red stars and very little active star formation.

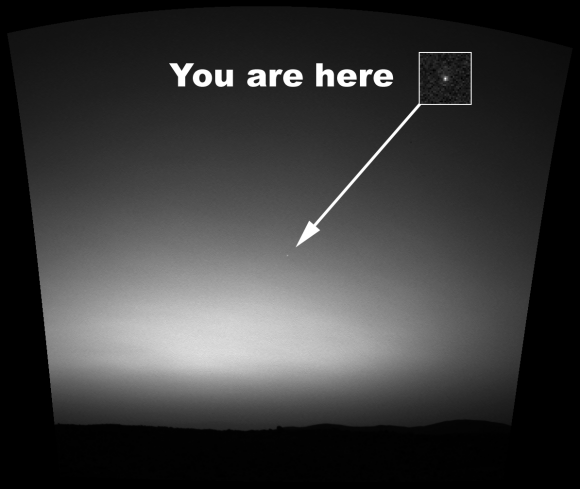

Despite the Andromeda Galaxy containing about 1 trillion stars and the Milky Way containing about 300 billion, the chance of even two stars colliding is negligible because of the huge distances between them. However, both galaxies contain central supermassive black holes, which will converge near the center of the newly-formed galaxy.

This black hole merger will cause orbital energy to be transferred to stars, which will be moved to higher orbits over the course of millions of years. When the two black holes come within a light year of one another, they will emit gravitational waves that will radiate further orbital energy, until they merge completely.

Gas taken up by the combined black hole could create a luminous quasar or an active nucleus to form at the center of the galaxy. And last, the effects of a black hole merger could also kick stars out of the larger galaxy, resulting in hypervelocity rogue stars that could even carry their planets with them.

Today, it is understood that galactic collisions are a common feature in our Universe. Astronomy now frequently simulate them on computers, which realistically simulate the physics involved – including gravitational forces, gas dissipation phenomena, star formation, and feedback.

And be sure to check out this video of the impending galactic collision, courtesy of NASA:

We have written many articles about galaxies for Universe Today. Here’s What is Galactic Cannibalism?, Watch Out! Galactic Collisions Could Snuff Out Star Formation, New Hubble Release: Dramatic Galaxy Collision, A Virtual Galactic Smash-Up!, It’s Inevitable: Milky Way, Andromeda Galaxy Heading for Collision, A Cosmic Collision: Our Best View Yet of Two Distant Galaxies Merging, and Determining the Galaxy Collision Rate.

If you’d like more info on galaxies, check out Hubblesite’s News Releases on Galaxies, and here’s NASA’s Science Page on Galaxies.

We have also recorded an episode of Astronomy Cast about galaxies – Episode 97: Galaxies.

Sources: