Four fundamental forces govern all interactions within the Universe. They are weak nuclear forces, strong nuclear forces, electromagnetism, and gravity. Of these, gravity is perhaps the most mysterious. While it has been understood for some time how this law of physics operates on the macro-scale – governing our Solar System, galaxies, and superclusters – how it interacts with the three other fundamental forces remains a mystery.

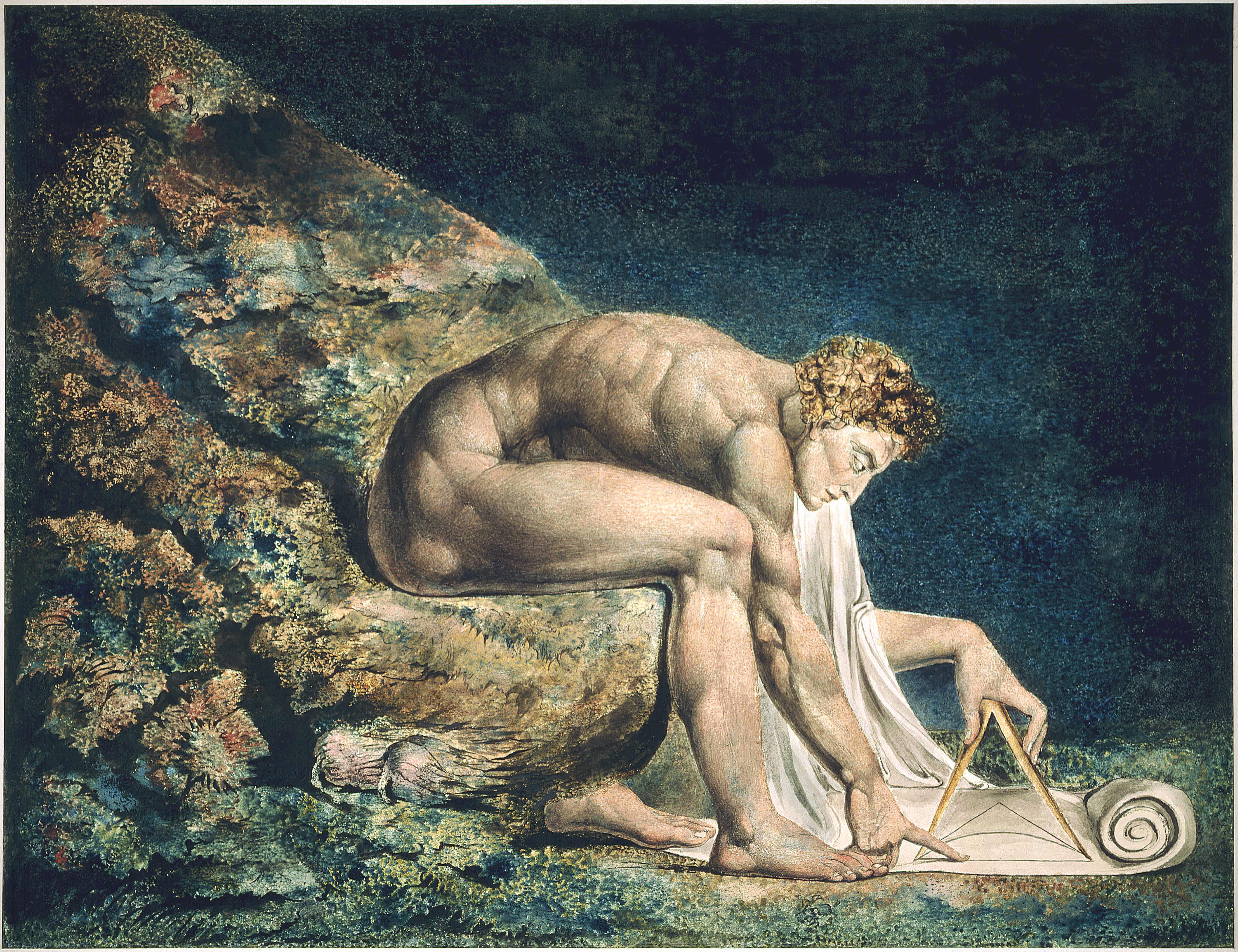

Naturally, human beings have had a basic understanding of this force since time immemorial. And when it comes to our modern understanding of gravity, credit is owed to one man who deciphered its properties and how it governs all things great and small – Sir Isaac Newton. Thanks to this 17th century English physicist and mathematician, our understanding of the Universe and the laws that govern it would forever be changed.

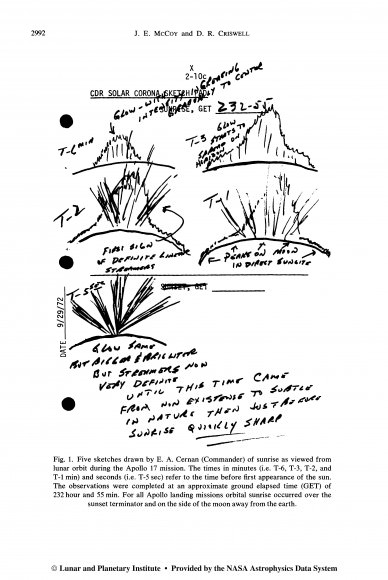

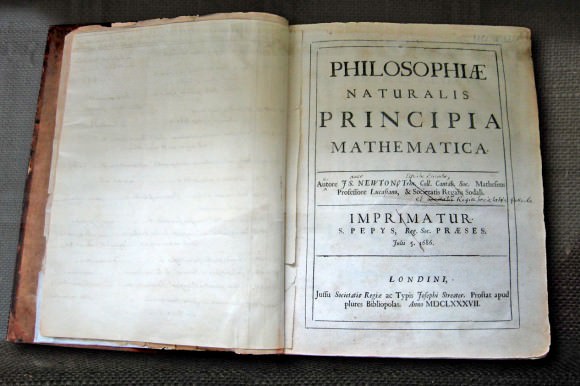

While we are all familiar with the iconic image of a man sitting beneath an apple tree and having one fall on his head, Newton’s theories on gravity also represented a culmination of years worth of research, which in turn was based on centuries of accumulated knowledge. He would present these theories in his magnum opus, Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica (“Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy”), which was first published in 1687.

In this volume, Newton laid out what would come to be known as his Three Laws of Motion, which were derived from Johannes Kepler’s Laws of Planetary Motion and his own mathematical description of gravity. These laws would lay the foundation of classical mechanics, and would remain unchallenged for centuries – until the 20th century and the emergence of Einstein’s Theory of Relativity.

Physics by 17th Century:

The 17th century was a very auspicious time for the sciences, with major breakthroughs occurring in the fields of mathematics, physics, astronomy, biology and chemistry. Some of the greatest developments in the period include the development of the heliocentric model of the Solar System by Nicolaus Copernicus, the pioneering work with telescopes and observational astronomy by Galileo Galilei, and the development of modern optics.

It was also during this period that Johannes Kepler developed his Laws of Planetary Motion. Formulated between 1609 and 1619, these laws described the motion of the then-known planets (Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn) around the Sun. They stated that:

- Planets move around the Sun in ellipses, with the Sun at one focus

- The line connecting the Sun to a planet sweeps equal areas in equal times.

- The square of the orbital period of a planet is proportional to the cube (3rd power) of the mean distance from the Sun in (or in other words–of the”semi-major axis” of the ellipse, half the sum of smallest and greatest distance from the Sun).

These laws resolved the remaining mathematical issues raised by Copernicus’ heliocentric model, thus removing all doubt that it was the correct model of the Universe. Working from these, Sir Isaac Newton began considering gravitation and its effect on the orbits of planets.

Newton’s Three Laws:

In 1678, Newton suffered a complete nervous breakdown due to overwork and a feud with fellow astronomer Robert Hooke. For the next few years, he withdrew from correspondence with other scientists, except where they initiated it, and renewed his interest in mechanics and astronomy. In the winter of 1680-81, the appearance of a comet, about which he corresponded with John Flamsteed (England’s Astronomer Royal) also renewed his interest in astronomy.

After reviewing Kepler’s Laws of Motion, Newton developed a mathematical proof that the elliptical form of planetary orbits would result from a centripetal force inversely proportional to the square of the radius vector. Newton communicated these results to Edmond Halley (discoverer of “Haley’s Comet”) and to the Royal Society in his De motu corporum in gyrum.

This tract, published in 1684, contained the seed of what Newton would expand to form his magnum opus, the Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica. This treatise, which was published in July of 1687, contained Newton’s three laws of motion, which stated that:

- When viewed in an inertial reference frame, an object either remains at rest or continues to move at a constant velocity, unless acted upon by an external force.

- The vector sum of the external forces (F) on an object is equal to the mass (m) of that object multiplied by the acceleration vector (a) of the object. In mathematical form, this is expressed as: F=ma

- When one body exerts a force on a second body, the second body simultaneously exerts a force equal in magnitude and opposite in direction on the first body.

Together, these laws described the relationship between any object, the forces acting upon it and the resulting motion, laying the foundation for classical mechanics. The laws also allowed Newton to calculate the mass of each planet, the flattening of the Earth at the poles, and the bulge at the equator, and how the gravitational pull of the Sun and Moon create the Earth’s tides.

In the same work, Newton presented a calculus-like method of geometrical analysis using ‘first and last ratios’, worked out the speed of sound in air (based on Boyle’s Law), accounted for the procession of the equinoxes (which he showed were a result of the Moon’s gravitational attraction to the Earth), initiated the gravitational study of the irregularities in the motion of the moon, provided a theory for the determination of the orbits of comets, and much more.

Newton and the “Apple Incident”:

The story of Newton coming up with his theory of universal gravitation as a result of an apple falling on his head has become a staple of popular culture. And while it has often been argued that the story is apocryphal and Newton did not devise his theory at any one moment, Newton himself told the story many times and claimed that the incident had inspired him.

In addition, the writing’s of William Stukeley – an English clergyman, antiquarian and fellow member of the Royal Society – have confirmed the story. But rather than the comical representation of the apple striking Newton on the head, Stukeley described in his Memoirs of Sir Isaac Newton’s Life (1752) a conversation in which Newton described pondering the nature of gravity while watching an apple fall.

“…we went into the garden, & drank thea under the shade of some appletrees; only he, & my self. amidst other discourse, he told me, he was just in the same situation, as when formerly, the notion of gravitation came into his mind. “why should that apple always descend perpendicularly to the ground,” thought he to himself; occasion’d by the fall of an apple…”

John Conduitt, Newton’s assistant at the Royal Mint (who eventually married his niece), also described hearing the story in his own account of Newton’s life. According to Conduitt, the incident took place in 1666 when Newton was traveling to meet his mother in Lincolnshire. While meandering in the garden, he contemplated how gravity’s influence extended far beyond Earth, responsible for the falling of apple as well as the Moon’s orbit.

Similarly, Voltaire wrote n his Essay on Epic Poetry (1727) that Newton had first thought of the system of gravitation while walking in his garden and watching an apple fall from a tree. This is consistent with Newton’s notes from the 1660s, which show that he was grappling with the idea of how terrestrial gravity extends, in an inverse-square proportion, to the Moon.

However, it would take him two more decades to fully develop his theories to the point that he was able to offer mathematical proofs, as demonstrated in the Principia. Once that was complete, he deduced that the same force that makes an object fall to the ground was responsible for other orbital motions. Hence, he named it “universal gravitation”.

Various trees are claimed to be “the” apple tree which Newton describes. The King’s School, Grantham, claims their school purchased the original tree, uprooted it, and transported it to the headmaster’s garden some years later. However, the National Trust, which holds the Woolsthorpe Manor (where Newton grew up) in trust, claims that the tree still resides in their garden. A descendant of the original tree can be seen growing outside the main gate of Trinity College, Cambridge, below the room Newton lived in when he studied there.

Newton’s work would have a profound effect on the sciences, with its principles remaining canon for the following 200 years. It also informed the concept of universal gravitation, which became the mainstay of modern astronomy, and would not be revised until the 20th century – with the discovery of quantum mechanics and Einstein’s theory of General Relativity.

We have written many interesting articles about gravity here at Universe Today. Here is Who was Sir Isaac Newton?, Who Was Galileo Galilei?, What Is the Force of Gravity?, and What is the Gravitational Constant?

Astronomy Cast has some two good episodes on the subject. Here’s Episode 37: Gravitational Lensing, and Episode 102: Gravity,

Sources:

![A predicted consequence of Planet Nine is that a second set of confined objects should also exist. These objects are forced into positions at right angles to Planet Nine and into orbits that are perpendicular to the plane of the solar system. Five known objects (blue) fit this prediction precisely. Credit: Caltech/R. Hurt (IPAC) [Diagram was created using WorldWide Telescope.]](https://www.universetoday.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/p9_kbo_extras_orbits_2_1-580x326.jpg)