Volcanoes are renowned for their destructive power. In fact, there are few forces of nature that rival their sheer, awesome might, or have left as big of impact on the human psyche. Who hasn’t heard of tales of Mt. Vesuvius erupting and burying Pompeii? There’s also the Minoan Eruption, the eruption that took place in the 2nd millennium BCE on the isle of Santorini and devastated the Minoan settlement there.

In Japan, Hawaii, South American and all across the Pacific, there are countless instances of eruptions taking a terrible toll. And who can forget modern-day eruptions like Mount St. Helens? But would it surprise you to know that despite their destructive power, volcanoes actually come with their share of benefits? From enriching the soil to creating new landmasses, volcanoes are actually a productive force as well.

Soil Enrichment:

Volcanic eruptions result in ash being dispersed over wide areas around the eruption site. And depending on the chemistry of the magma from which it erupted, this ash will be contain varying amounts of soil nutrients. While the most abundant elements in magma are silica and oxygen, eruptions also result in the release of water, carbon dioxide (CO²), sulfur dioxide (SO²), hydrogen sulfide (H²S), and hydrogen chloride (HCl), amongst others.

In addition, eruptions release bits of rock such as potolivine, pyroxene, amphibole, and feldspar, which are in turn rich in iron, magnesium, and potassium. As a result, regions that have large deposits of volcanic soil (i.e. mountain slopes and valleys near eruption sites) are quite fertile. For example, most of Italy has poor soils that consist of limestone rock.

But in the regions around Naples (the site of Mt. Vesuvius), there are fertile stretches of land that were created by volcanic eruptions that took place 35,000 and 12,000 years ago. The soil in this region is rich because volcanic eruption deposit the necessary minerals, which are then weathered and broken down by rain. Once absorbed into the soil, they become a steady supply of nutrients for plant life.

Hawaii is another location where volcanism led to rich soil, which in turn allowed for the emergence of thriving agricultural communities. Between the 15th and 18th centuries on the islands of Kauai, O’ahu and Molokai, the cultivation of crops like taros and sweet potatoes allowed for the rise of powerful chiefdoms and the flowering of the culture we associate with Hawaii today.

Volcanic Land Formations:

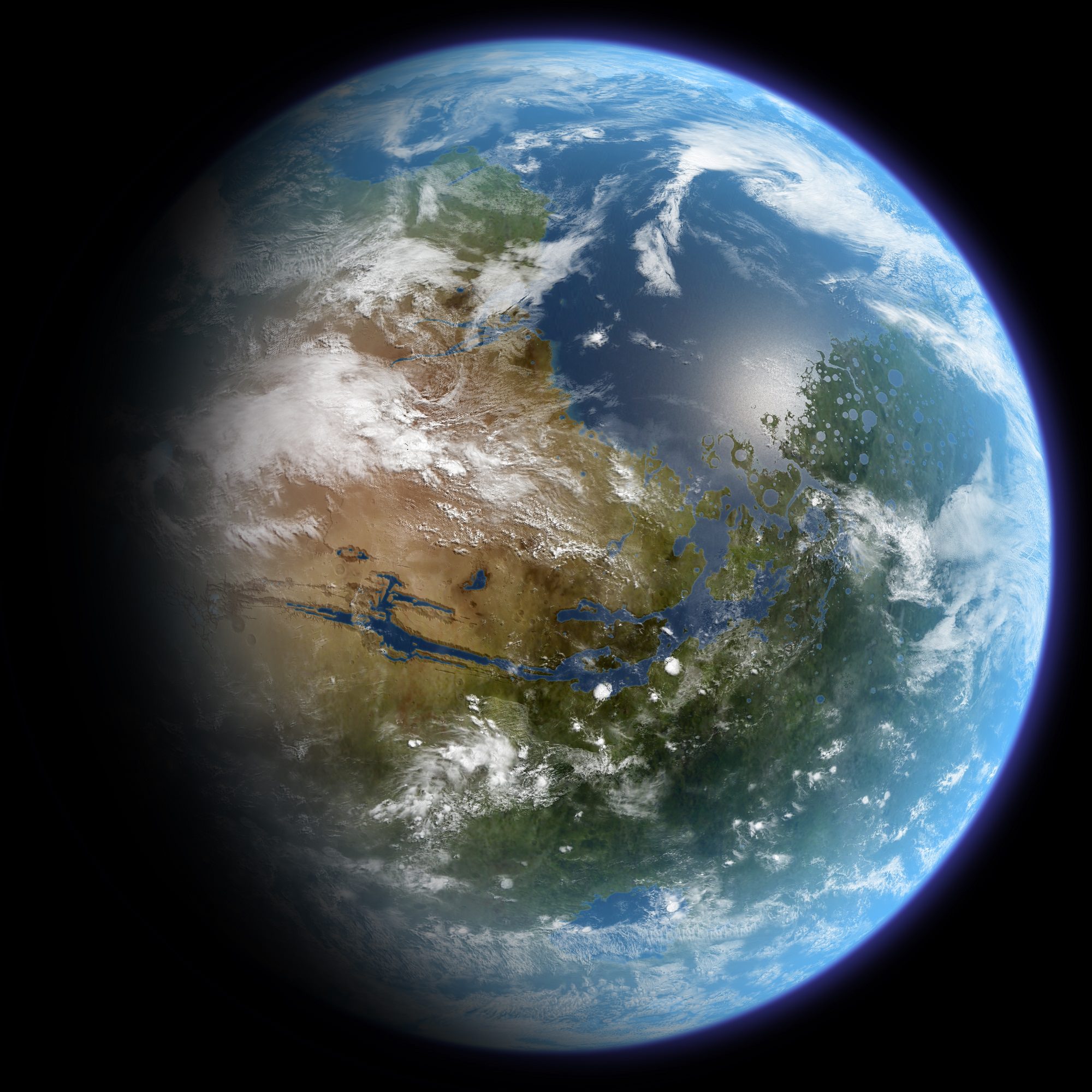

In addition to scattering ash over large areas of land, volcanoes also push material to the surface that can result in the formation of new islands. For example, the entire Hawaiian chain of islands was created by the constant eruptions of a single volcanic hot spot. Over hundreds of thousands of years, these volcanoes breached the surface of the ocean becoming habitable islands, and rest stops during long sea journeys.

This is the case all across the Pacific, were island chains such as Micronesia, the Ryukyu Islands (between Taiwan and Japan), the Aleutian Islands (off the coast of Alaska), the Mariana Islands, and Bismark Archipelago were all formed along arcs that are parallel and close to a boundary between two converging tectonic plates.

Much the same is true of the Mediterranean. Along the Hellenic Arc (in the eastern Mediterranean), volcanic eruptions led to the creation of the Ionian Islands, Cyprus and Crete. The nearby South Aegean Arc meanwhile led to the formation of Aegina, Methana, Milos, Santorini and Kolumbo, and Kos, Nisyros and Yali. And in the Caribbean, volcanic activity led to the creation of the Antilles archipelago.

Where these islands formed, unique species of plants and animals evolved into new forms on these islands, creating balanced ecosystems and leading to new levels of biodiversity.

Volcanic Minerals and Stones:

Another benefits to volcanoes are the precious gems, minerals and building materials that eruptions make available. For instance, stones like pumice volcanic ash and perlite (volcanic glass) are all mined for various commercial uses. These include acting as abrasives in soaps and household cleaners. Volcanic ash and pumice are also used as a light-weight aggregate for making cement.

The finest grades of these volcanic rocks are used in metal polishes and for woodworking. Crushed and ground pumice are also used for loose-fill insulation, filter aids, poultry litter, soil conditioner, sweeping compound, insecticide carrier, and blacktop highway dressing.

Perlite is also used as an aggregate in plaster, since it expands rapidly when heated. In precast walls, it too is used as an aggregate in concrete. Crushed basalt and diasbase are also used for road metal, railroad ballast, roofing granules, or as protective arrangements for shorelines (riprap). High-density basalt and diabase aggregate are used in the concrete shields of nuclear reactors.

Hardened volcanic ash (called tuff) makes an especially strong, lightweight building material. The ancient Romans combined tuff and lime to make a strong, lightweight concrete for walls, and buildings. The roof of the Pantheon in Rome is made of this very type of concrete because it’s so lightweight.

Precious metals that are often found in volcanoes include sulfur, zinc, silver, copper, gold, and uranium. These metals have a wide range of uses in modern economies, ranging from fine metalwork, machinery and electronics to nuclear power, research and medicine. Precious stones and minerals that are found in volcanoes include opals, obsidian, fire agate, flourite, gypsum, onyx, hematite, and others.

Global Cooling:

Volcanoes also play a vital role in periodically cooling off the planet. When volcanic ash and compounds like sulfur dioxide are released into the atmosphere, it can reflect some of the Sun’s rays back into space, thereby reducing the amount of heat energy absorbed by the atmosphere. This process, known as “global dimming”, therefore has a cooling effect on the planet.

The link between volcanic eruptions and global cooling has been the subject of scientific study for decades. In that time, several dips have been observed in global temperatures after large eruptions. And though most ash clouds dissipate quickly, the occasional prolonged period of cooler temperatures have been traced to particularly large eruptions.

Because of this well-established link, some scientists have recommended that sulfur dioxide and other be released into the atmosphere in order to combat global warming, a process which is known as ecological engineering.

Hot Springs And Geothermal Energy:

Another benefit of volcanism comes in the form of geothermal fields, which is an area of the Earth characterized by a relatively high heat flow. These fields, which are the result of present, or fairly recent magmatic activity, come in two forms. Low temperature fields (20-100°C) are due to hot rock below active faults, while high temperature fields (above 100°C) are associated with active volcanism.

Geothermal fields often create hot springs, geysers and boiling mud pools, which are often a popular destination for tourists. But they can also be harnessed for geothermal energy, a form of carbon-neutral power where pipes are placed in the Earth and channel steam upwards to turn turbines and generate electricity.

In countries like Kenya, Iceland, New Zealand, the Phillipines, Costa Rica and El Salvador, geothermal power is responsible for providing a significant portion of the country’s power supply – ranging from 14% in Costa Rica to 51% in Kenya. In all cases, this is due to the countries being in and around active volcanic regions that allow for the presence of abundant geothermal fields.

Outgassing and Atmospheric Formation:

But by far, the most beneficial aspect of volcanoes is the role they play in the formation of a planet’s atmosphere. In short, Earth’s atmosphere began to form after its formation 4.6 billion eyars ago, when volcanic outgassing led to the creation of gases stored in the Earth’s interior to collect around the surface of the planet. Initially, this atmosphere consisted of hydrogen sulfide, methane, and 10 to 200 times as much carbon dioxide as today’s atmosphere.

After about half a billion years, Earth’s surface cooled and solidified enough for water to collect on it. At this point, the atmosphere shifted to one composed of water vapor, carbon dioxide and ammonia (NH³). Much of the carbon dioxide dissolved into the oceans, where cyanobacteria developed to consume it and release oxygen as a byproduct. Meanwhile, the ammonia began to be broken down by photolysis, releasing the hydrogen into space and leaving the nitrogen behind.

Another key role played by volcanism occurred 2.5 billion years ago, during the boundary between the Archaean and Proterozoic Eras. It was at this point that oxygen began to appear in our oxygen due to photosynthesis – which is referred to asthe “Great Oxidation Event”. However, according to recent geological studies, biomarkers indicate that oxygen-producing cyanobacteria were releasing oxygen at the same levels there are today. In short, the oxygen being produced had to be going somewhere for it not to appear in the atmosphere.

The lack of terrestrial volcanoes is believed to be responsible. During the Archaean Era, there were only submarine volcanoes, which had the effect of scrubbing oxygen from the atmosphere, binding it into oxygen containing minerals. By the Archaean/Proterozoic boundary, stabilized continental land masses arose, leading to terrestrial volcanoes. From this point onward, markers show that oxygen began appearing in the atmosphere.

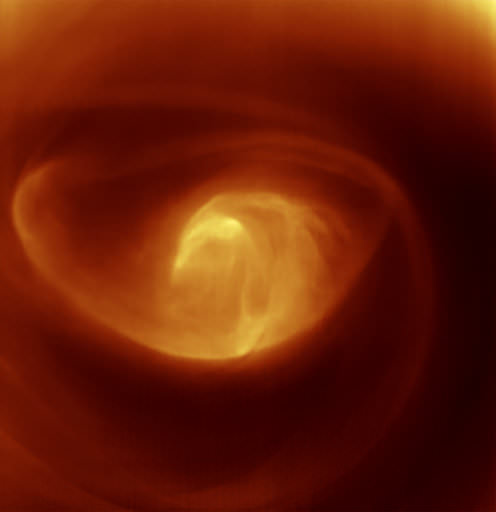

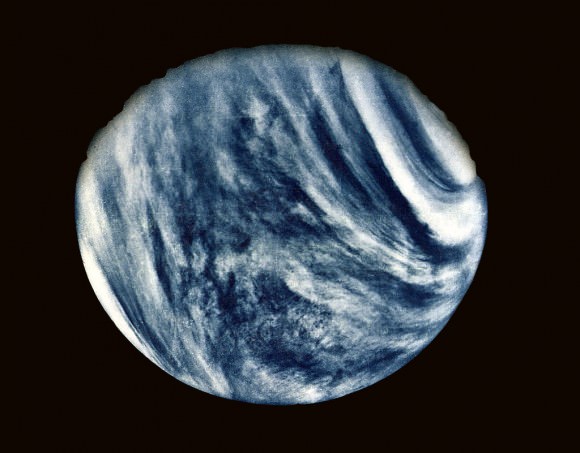

Volcanism also plays a vital role in the atmospheres of other planets. Mercury’s thin exosphere of hydrogen, helium, oxygen, sodium, calcium, potassium and water vapor is due in part of volcanism, which periodically replenishes it. Venus’ incredibly dense atmosphere is also believed to be periodically replenished by volcanoes on its surface.

And Io, Jupiter’s volcanically active moon, has an extremely tenuous atmosphere of sulfur dioxide (SO²), sulfur monoxide (SO), sodium chloride (NaCl), sulfur monoxide (SO), atomic sulfur (S) and oxygen (O). All of these gases are provided and replenished by the many hundreds of volcanoes situated across the moon’s surface.

As you can see, volcanoes are actually a pretty creative force when all is said and done. In fact, us terrestrial organisms depend on them for everything from the air we breathe, to the rich soil that produces our food, to the geological activity that gives rise to terrestrial renewal and biological diversity.

We have written many articles about volcanoes for Universe Today. Here’s an article about extinct volcanoes, and here’s an article about active volcanoes. Here’s an article about volcanoes.

Want more resources on the Earth? Here’s a link to NASA’s Human Spaceflight page, and here’s NASA’s Visible Earth.

Astronomy Cast also has relevant episodes on the subject Earth, as part of our tour through the Solar System – Episode 51: Earth.