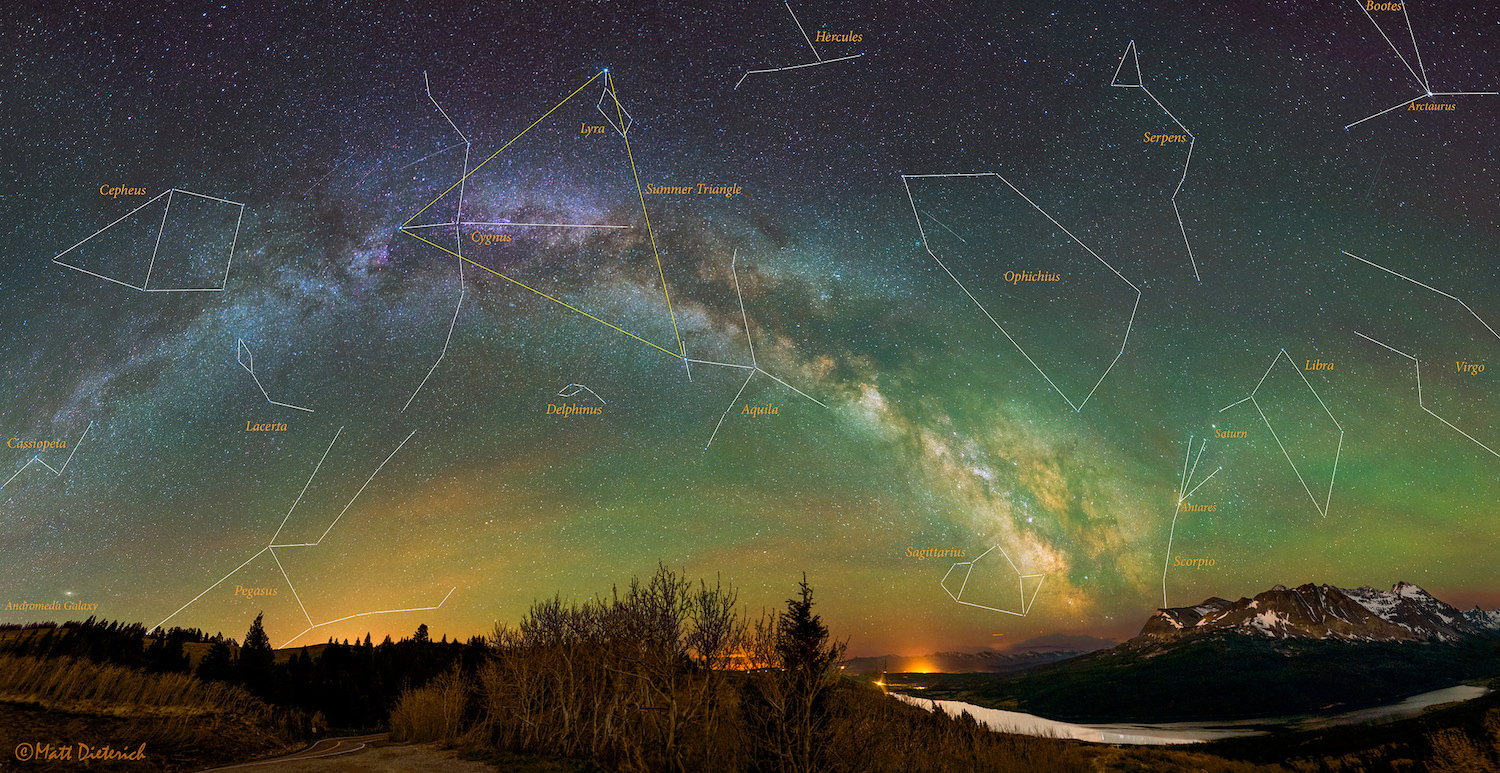

What comes to mind when you look up at the night sky and spot the constellations? Is it a grand desire to explore deep into space? Is it the feeling of awe and wonder, that perhaps these shapes in the sky represent something? Or is the sense that, like countless generations of human beings who have come before you, you are staring into the heavens and seeing patterns? If the answer to any of the above is yes, then you are in good company!

While most people can name at least one constellation, very few know the story of where they came from. Who were the first people to spot them? Where do their names come from? And just how many constellations are there in the sky? Here are a few of the answers, followed by a list of every known constellation, and all the relevant information pertaining to them.

Definition:

A constellation is essentially a specific area of the celestial sphere, though the term is more often associated with a chance grouping of stars in the night sky. Technically, star groupings are known as asterisms, and the practice of locating and assigning names to them is known as asterism. This practice goes back thousands of years, possibly even to the Upper Paleolithic. In fact, archaeological studies have identified markings in the famous cave paintings at Lascaux in southern France (ca. 17,300 years old) that could be depictions of the Pleiades cluster and Orion’s Belt.

There are currently 88 officially recognized constellations in total, which together cover the entire sky. Hence, any given point in a celestial coordinate system can unambiguously be assigned to a constellation. It is also a common practice in modern astronomy, when locating objects in the sky, to indicate which constellation their coordinates place them in proximity to, thus conveying a rough idea of where they can be found.

The word constellation has its roots in the Late Latin term constellatio, which can be translated as “set of stars”. A more functional definition would be a recognizable pattern of stars whose appearance is associated with mythical characters, creatures, or certain characteristics. It’s also important to note that colloquial usage of the word “constellation” does not generally differentiate between an asterism and the area surrounding one.

Typically, stars in a constellation have only one thing in common – they appear near each other in the sky when viewed from Earth. In reality, these stars are often very distant from each other and only appear to line up based on their immense distance from Earth. Since stars also travel on their own orbits through the Milky Way, the star patterns of the constellations change slowly over time.

History of Observation:

It is believed that since the earliest humans walked the Earth, the tradition of looking up at the night sky and assigning names and characters to them existed. However, the earliest recorded evidence of asterism and constellation-naming comes to us from ancient Mesopotamia, and in the form of etchings on clay tablets that are dated to around ca. 3000 BCE.

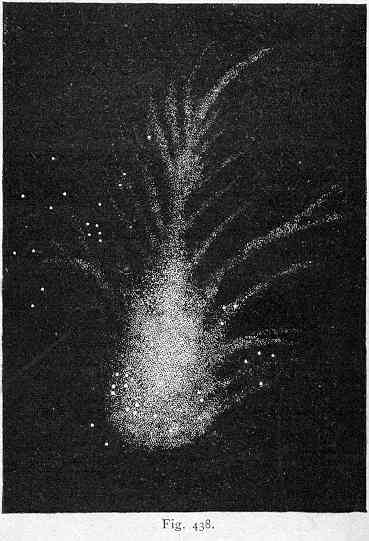

However, the ancient Babylonians were the first to recognize that astronomical phenomena are periodic and can be calculated mathematically. It was during the middle Bronze Age (ca. 2100 – 1500 BCE) that the oldest Babylonian star catalogs were created, which would later come to be consulted by Greek, Roman and Hebrew scholars to create their own astronomical and astrological systems.

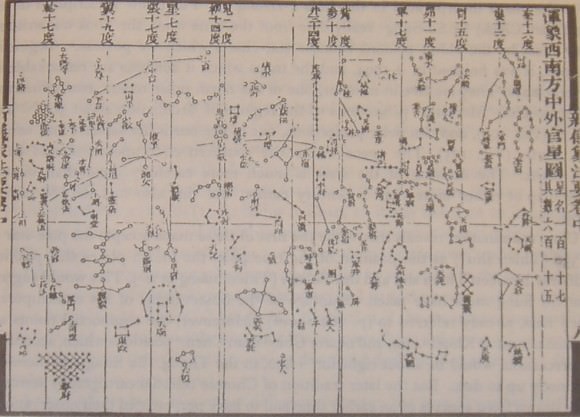

In ancient China, astronomical traditions can be traced back to the middle Shang Dynasty (ca. 13th century BCE), where oracle bones unearthed at Anyang were inscribed with the names of star. The parallels between these and earlier Sumerian star catalogs suggest they did no arise independently. Astronomical observations conducted in the Zhanguo period (5th century BCE) were later recorded by astronomers in the Han period (206 BCE – 220 CE), giving rise to the single system of classic Chinese astronomy.

In India, the earliest indications of an astronomical system being developed are attributed to the Indus Valley Civilization (3300–1300 BCE). However, the oldest recorded example of astronomy and astrology is the Vedanga Jyotisha, a study which is part of the wider Vedic literature (i.e. religious) of the time, and which is dated to 1400-1200 BCE.

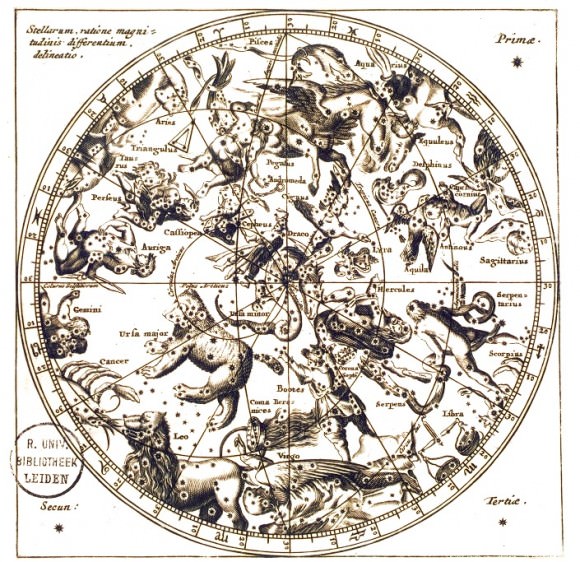

By the 4th century BCE, the Greeks adopted the Babylonian system and added several more constellations to the mix. By the 2nd century CE, Claudius Ptolemaus (aka. Ptolemy) combined all 48 known constellations into a single system. His treatise, known as the Almagest, would be used by medieval European and Islamic scholars for over a thousand years to come.

Between the 8th and 15th centuries, the Islamic world experienced a burst of scientific development, reaching from the Al-Andus region (modern-day Spain and Portugal) to Central Asia and India. Advancements in astronomy and astrology closely paralleled those made in other fields, where ancient and classical knowledge was assimilated and expanded on.

In turn, Islamic astronomy later had a significant influence on Byzantine and European astronomy, as well as Chinese and West African astronomy (particularly in the Mali Empire). A significant number of stars in the sky, such as Aldebaran and Altair, and astronomical terms such as alidade, azimuth, and almucantar, are still referred to by their Arabic names.

From the end of the 16th century onward, the age of exploration gave rise to circumpolar navigation, which in turn led European astronomers to witness the constellations in the South Celestial Pole for the first time. Combined with expeditions that traveled to the Americas, Africa, Asia, and all other previously unexplored regions of the planet, modern star catalogs began to emerge.

IAU Constellations:

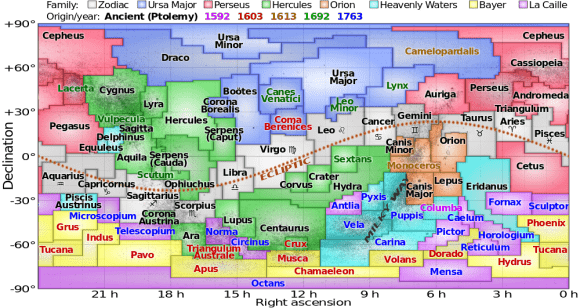

The International Astronomical Union (IAU) currently has a list of 88 accepted constellations. This is largely due to the work of Henry Norris Russell, who in 1922, aided the IAU in dividing the celestial sphere into 88 official sectors. In 1930, the boundaries between these constellations were devised by Eugène Delporte, along vertical and horizontal lines of right ascension and declination.

The IAU list is also based on the 48 constellations listed by Ptolemy in his Almagest, with early modern modifications and additions by subsequent astronomers – such as Petrus Plancius (1552 – 1622), Johannes Hevelius (1611 – 1687), and Nicolas Louis de Lacaille (1713 – 1762).

However, the data Delporte used was dated to the late 19th century, back when the suggestion was first made to designate boundaries in the celestial sphere. As a consequence, the precession of the equinoxes has already led the borders of the modern star map to become somewhat skewed, to the point that they are no longer vertical or horizontal. This effect will increase over the centuries and will require revision.

Not a single new constellation or constellation name has been postulated in centuries. When new stars are discovered, astronomers simply add them to the constellation they are closest to. So consider the information below, which lists all 88 constellations and provides information about each, to be up-to-date! We even threw in a few links about the zodiac, its meanings, and dates.

Enjoy your reading!

-A

-B

-C

- Caleum

- Camelopardalis

- Cancer

- Canes Venatici

- Canis Major

- Canis Minor

- Capricornus

- Carina

- Cassiopeia

- Centaurus

- Cepheus

- Cetus

- Chamaeleon

- Circinus

- Columba

- Coma Berenices

- Corona Australis

- Corona Borealis

- Corvus

- Crater

- Crux

- Cygnus

-D

-E

-F

-G

-H

-I

-L

-M

-N

-O

-P

-R

-S

- Sagitta

- Sagittarius

- Scorpius

- Sculptor

- Scutum

- Serpens Caput

- Serpens Cauda

- Sextans

- Southern Cross Constellation