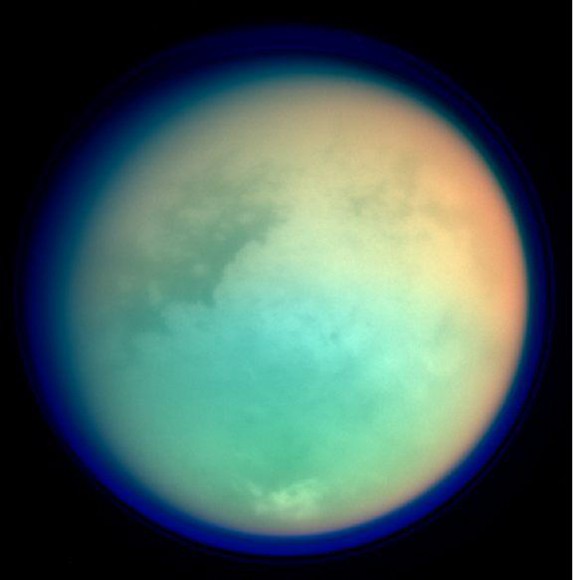

In the ongoing drive to unlock the secrets of Saturn and its system of moons, some truly fascinating and awe-inspiring things have been discovered. In addition to things like methane lakes and propane-rich atmospheres (Titan) to moon’s that resemble the Death Star (Mimas), it is also becoming abundantly clear that planet’s beyond Earth may harbor interior oceans and even the extra-terrestrial organisms.

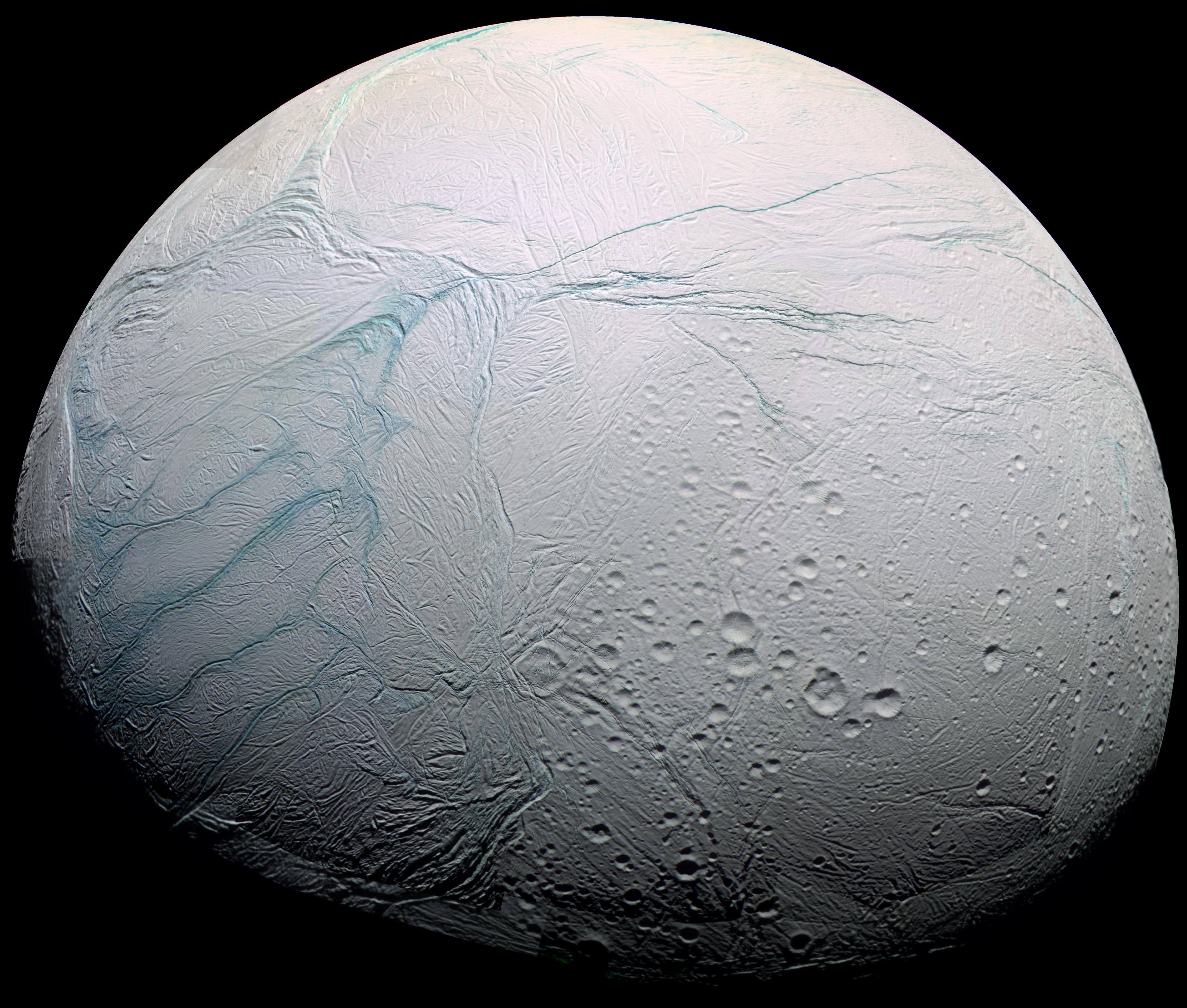

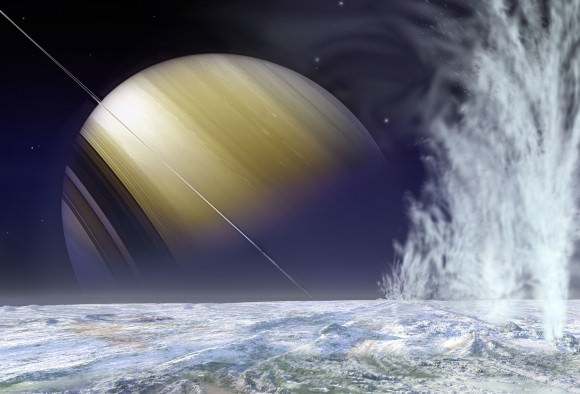

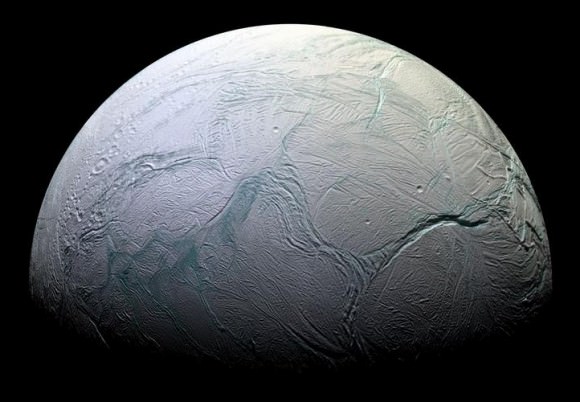

Nowhere is this more apparent than on Enceladus, Saturn’s sixth largest moon, which also possesses some of the most interesting characteristics in the outer Solar System. These include long veins of blue ice that resemble stripes, not to mention amazing plumes of water ice that have been spotted periodically blasting out of the moon’s southern pole. These, in turn, raise the possibility of liquid water beneath the surface, and possibly even life!

Discovery and Naming:

Discovered in 1789 by William Herschel, Enceladus is named after one of the giants in Greek mythology. In fact, all of the large moons of Saturn are named after the Titans, as suggested by William Herschel’s son, John Herschel. He chose these names because Saturn (known in Greek mythology as Kronos) was the father of the Titans.

In contrast, in accordance with the IAU naming conventions for Enceladus, features are named after characters and places from the classic story One Thousand and One Nights (aka. Arabian Nights). Impact craters are named after characters, whereas other feature types – such as fossae (long, narrow depressions), dorsa (ridges), planitia (plains), and sulci (long parallel grooves), are named after places.

Size, Mass and Orbit:

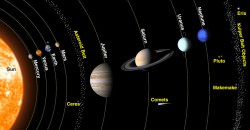

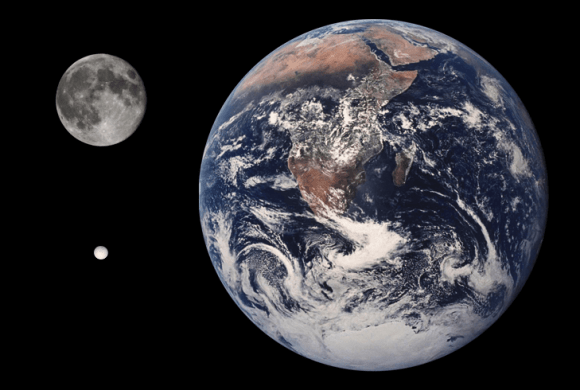

With a mean radius of 252 km, Enceladus is equivalent in size to 0.0395 Earths (or 0.1451 Moons). But with a mass of 1.08 ×1020 kg, it is only 0.000018 as massive. The planet has a very minor eccentricity (0.0047) and orbits Saturn at an average distance (semi-major axis) of 237,948 km, between the orbits of Mimas and Tethys.

Enceladus takes 32.9 hours (1.37 days) to complete a single orbit around Saturn, and is currently in a 2:1 mean-motion orbital resonance with Dione; meaning that it completes two orbits of Saturn for every orbit completed by Dione. This forced resonance is what maintains Enceladus’s orbital eccentricity and results in tidal deformation, and the resulting heat dissipation is the main heating source for Enceladus’s geologic activity.

Like most of the larger natural satellites of Saturn, Enceladus rotates synchronously with its orbital period, keeping one face pointed toward Saturn. The planet also experiences forced libration, where it appears to oscillate relative to Saturn’s other moons – which may also provide Enceladus with an internal heat source.

Composition and Surface Features:

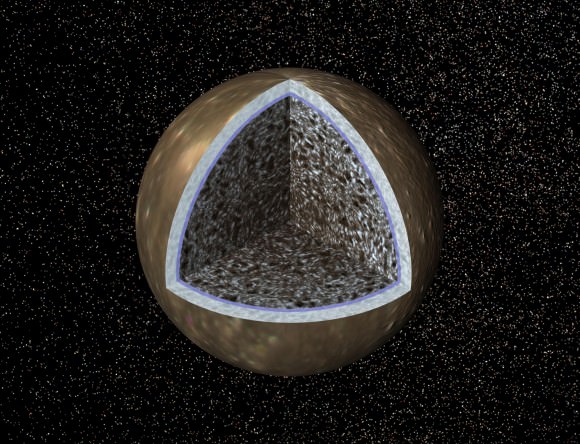

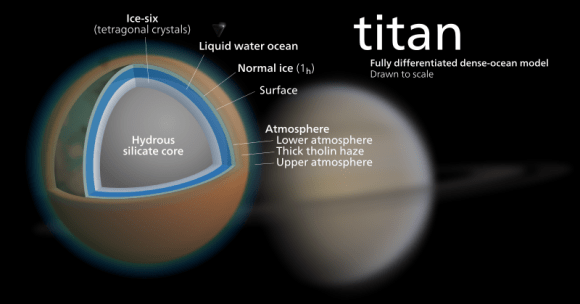

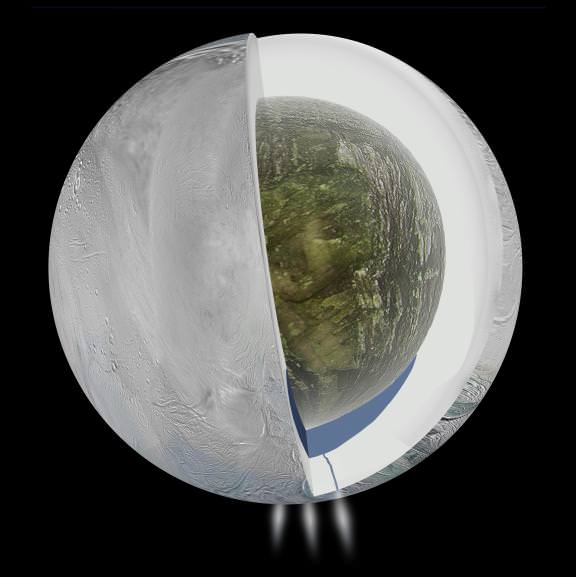

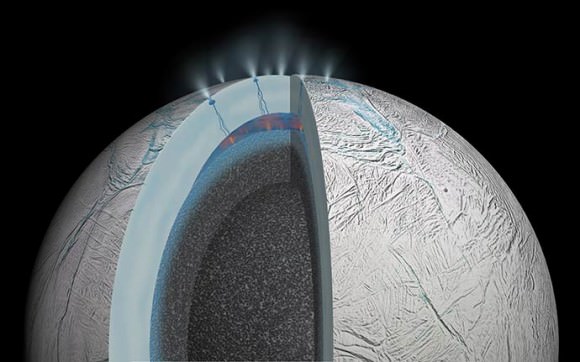

Enceladus has a density of 1.61 g/cm³, which is higher than Saturn’s other mid-sized, icy satellites, suggesting a composition that includes a greater percentage of silicates and iron. It is also believed to be largely differentiated between a geologically active core and an icy mantle, with a liquid water ocean nestled between.

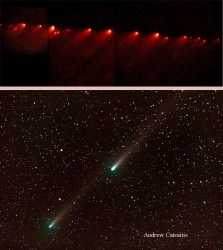

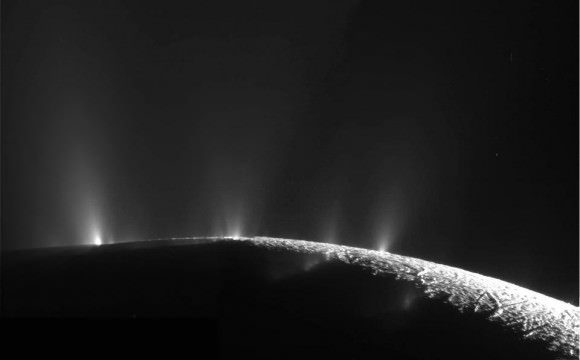

The existence of this liquid water ocean has been the subject of scientific debate since 2005, when scientists first observed plumes containing water vapor spewing from Enceladus’s south polar surface. These jets are capable of dispensing 250 kg of water vapor every second at speeds of up to 2,189 km/h (1,360 mph), and reaching 500 km into space.

In 2006, it was determined that Enceladus’s plumes are the source of Saturn’s E Ring and actively replenish it. According to measurements made by the Cassini-Huygens probe, these emissions are composed mostly of water vapor, as well as minor components like molecular nitrogen, methane, and carbon dioxide. Further observations noted the presence of simple hydrocarbons such as methane, propane, acetylene and formaldehyde.

The combined analysis of imaging, mass spectrometry, and magnetospheric data suggests that the observed south polar plume emanates from pressurized subsurface chambers. The intensity of the eruptions varies significantly due to changes in Enceladus’s orbit. Basically, the plumes are about four times brighter when Enceladus is at apoapsis (farthest from Saturn), which is consistent with geophysical calculations that predict that the south polar fissures will be under less compression, thus opening them wider.

The existence of subsurface water was confirmed thanks to evidence provided by the Cassini mission in 2014. This included gravity measurements obtained during the flybys of 2010-2012, which confirmed the existence of a south polar subsurface ocean of liquid water within Enceladus with a thickness of around 10 km.

In addition, during the July 14, 2005 flyby, the Cassini probe also detected the presence of escaping internal heat in the southern polar region. These temperatures were too high to be attributed to solar heating, and combined with the geyser activity, seemed to indicate that the interior of the planet is still geologically active.

Further studies from measurements of Enceladus’s libration as it orbits Saturn strongly suggest that the entire icy crust is detached from the rocky core, which would mean that the ocean beneath its surface is planet-wide. The amount of libration implies that this global ocean is about 26 to 31 kilometers in depth (compared to Earth’s average ocean depth of 3.7 kilometers).

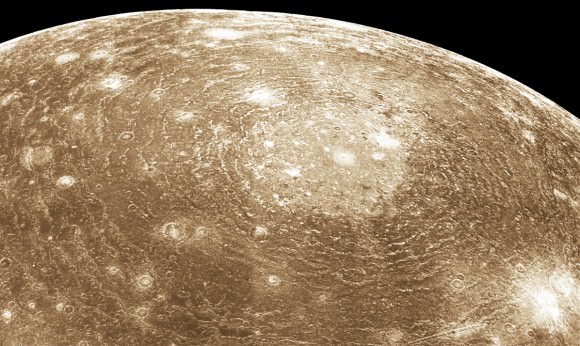

Observations of Enceladus’ surface has revealed five types of terrain – cratered terrain, smooth (young) terrain, ridged terrain (often bordering on smooth areas), linear cracks, scarps, troughs, and grooves. Surveys of the cratered terrain, smooth plains, and other features indicate a level of resurfacing that suggests that tectonics are an important factor in the geological history of Enceladus.

Recent observations by Cassini have provided a closer look at the crater distribution and size. These features have been named by the IAU after characters and places from Burton’s translation of The Book of One Thousand and One Nights – i.e. the Shahrazad crater, the Diyar plains, the Anbar depression.

The smooth plains are dominated by fresh clean ice, which gives Enceladus what is possibly the most reflective surface in the Solar System (with a visual geometric albedo of 1.38). These areas have few craters, which indicate that they are likely younger than a few hundred million years old. In addition, the relative youthfulness of these regions are an indication that cryovolcanism and other processes actively renew the surface.

The older terrain is not only cratered, but numerous fractures have also been observed – suggesting that the surface has been subject to extensive deformation since the craters formed. Some areas show regions with no craters, indicating major resurfacing events in the geologically recent past. The fissures, plains, corrugated terrain and other crustal deformations also indicate that Enceladus is geologically active.

One of the more dramatic types of tectonic features found on Enceladus are its rift canyons. These canyons can be up to 200 km long, 5–10 km wide, and 1 km deep. Such features are geologically young, because they cut across other tectonic features and have sharp topographic relief with prominent outcrops along the cliff faces.

Evidence of tectonics on Enceladus is also derived from grooved terrain, consisting of lanes of curved formations and ridges that often separate smooth plains from cratered regions. Deep fractures are another, which are often found in bands cutting across cratered terrain, and which were probably influenced by the formation of weakened regolith produced by impact craters.

Linear grooves can also be seen cutting across other terrain types, like the groove and ridge belts. Like the deep rifts, they are among the youngest features on Enceladus. However, some linear grooves have been softened like the craters nearby, suggesting that they are older. Ridges have also been observed on Enceladus, though they are relatively limited in extent and are up to one kilometer tall.

Other interesting features include the “Tiger stripes“: a series of fractures bounded on either side by ridges in the southern polar region that are are surrounded by mint-green-colored, coarse-grained water ice. These fractures appear to be the youngest features in this region, and combined with a lack of impact craters in this area, are further evidence of geological activity.

Atmosphere:

Saturn’s moon Enceladus has an atmosphere greater than that of all others in the Solar System, with the exception of Titan. The source of the atmosphere is attributed to the periodic cryovolcanism, which leads to gases and vapor escaping from the surface or the interior. Evidence of a tenuous atmosphere came from magnetometer readings provided by the Cassini‘s probe in 2005.

This consisted of an increased detection in the power of ion cyclotron waves, which are produced by the interaction of ionized particles and magnetic fields. During the next two encounters, the magnetometer team determined that gases in Enceladus’s atmosphere are concentrated over the south polar region, with atmospheric density away from the pole being much lower.

Much like the content of the jet plumes, this atmosphere is composed primarily of water vapor (91%), but also shows signs of minor components like molecular nitrogen (4%) and carbon dioxide (3.2%). There has also been evidence of simple hydrocarbons, which take the form of methane (1.7%) as well as trace amounts of propane, acetylene and formaldehyde.

Habitability:

Ever since the discovery of Enceladus’s geysers and evidence that suggested an interior ocean, scientists have speculated about the possibility of there being life on Enceladus. Because it reflects so much sunlight, the mean surface temperature at noon only reaches -198 °C, making it somewhat colder than other Cronian satellites. However, within the core, multiple indications of life exist.

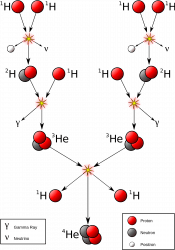

It’s resonance with Dione excites its orbital eccentricity, which tidal forces damp, resulting in tidal heating of its interior. This offers a possible explanation for its geological activity, and also suggests that its interior oceans are warmer closer to the core. In addition, geological models have indicated that the large rocky core is porous, allowing water to flow through it to pick up heat.

A model of Enceladus’s ocean created by Christopher R. Glein et al. (2015) suggests that it has an alkaline pH of 11 to 12. This high pH (alkaline) is interpreted to be a consequence of serpentinization of chondritic rock, which leads to the generation of molecular hydrogen (H²). This geochemical source of energy can be metabolized by methanogen microbes to provide energy for life.

The presence of an internal salty ocean with an energy source and simple organic compounds are all strong indications that microbes may exist closer to the core, where the water is warm and the basic building blocks of life exist.

Exploration:

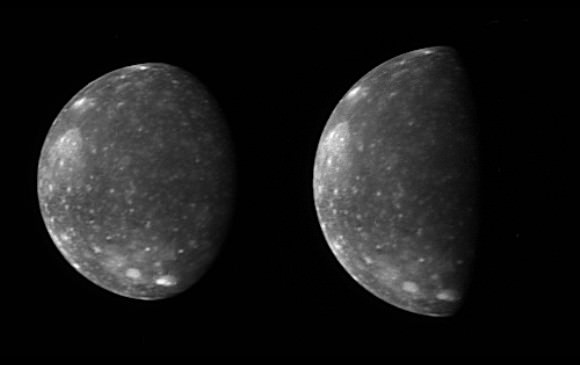

Although it was first discovered in the late 18th century, astronomers didn’t know much about this moon for many centuries. It was not until it was first visited in a series of flybys by NASA’s two Voyager spacecraft in the 1980’s that certain things began to become apparent about Enceladus.

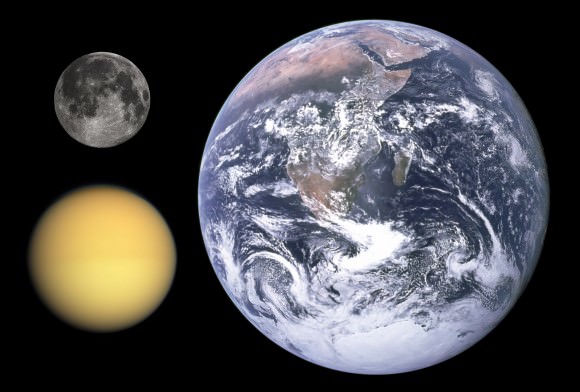

For starters, the Voyager missions showed that the planet has a diameter of only 500 km (310 miles), which makes it less than one-tenth the diameter of Saturn’s largest moon of Titan. They also noted that most of the surface is covered in fresh, clean ice; giving it a pure, snow-white appearance that also attracts close to 100% of the sunlight that strikes its surface.

The Voyager 1 mission also confirmed that Enceladus was embedded in the densest part of Saturn’s diffuse E-ring. Combined with the apparent youthful appearance of the surface, Voyager scientists suggested that the E-ring consisted of particles vented from Enceladus’s surface. The Voyager 2 mission provided better photographs than its predecessor, confirming the presence of a youthful surface, but also other features.

By 2005, the Cassini spacecraft began performing multiple close flybys of Enceladus, revealing its surface and environment in greater detail. In particular, Cassini discovered the water-rich plumes venting from the south polar region of Enceladus, which became the subject of much research and speculation.

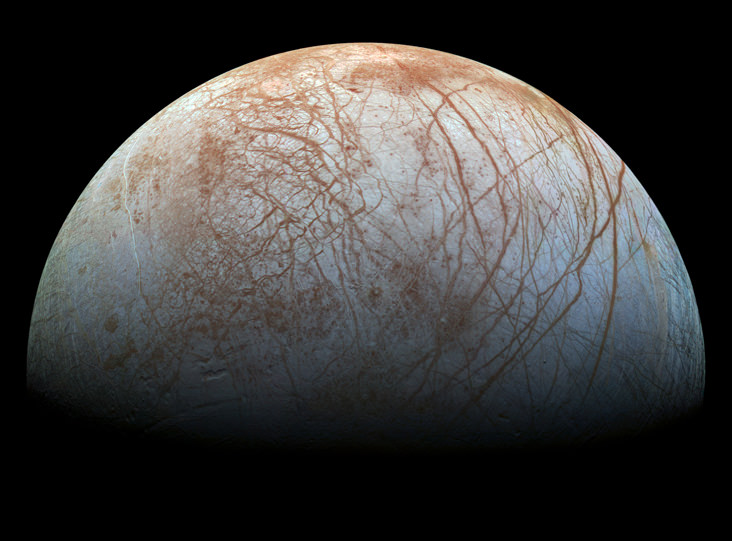

Cassini has provided strong evidence that Enceladus has an ocean with an energy source, nutrients and organic molecules, making Enceladus one of the best places for the study of potentially habitable environments for extraterrestrial life. By contrast, the water thought to be on Jupiter’s moon Europa is located under a much thicker layer of ice.

Cassini’s latest flyby took place on October 14th, 2015, passing the moon at an altitude of 1,839 kilometers (1,142 miles) above the northern polar region. This was the first time that Cassini had been able to observe the northern polar region, due to the fact that on all previous occasions, the northern region was experiencing its winter cycle and was concealed by darkness.

Cassini’s instruments took pictures of multiple surface features, including craters (many of which look like they are melting), fractures and wrinkles. The latter features are believed to be an indication that the moon’s spin rate has changed, which may be another indication that the surface has undergone multiple episodes of geologic activity over the course of much of its lifetime.

The discoveries Cassini has made at Enceladus have prompted studies into follow-up mission concepts. In 2013, NASA proposed a possible sample-return mission to Enceladus that would involve a low-cost orbiter. This mission would launch during the 2020s and last 15 years.

Another proposal for a probe flyby, known as Journey to Enceladus and Titan (JET) would analyze plume contents in-situ. Proposed in response to NASA’s 2010 Discovery Announcement of Opportunity, the mission would involve an orbiter conducting high-resolution mass spectroscopy surveys of Enceladus and Titan, assessing them for biological potential.

The German Aerospace Center has also proposed studying the habitability of Enceladus’s subsurface ocean using an Enceladus Explorer, and two astrobiology-oriented mission concepts (the Enceladus Life Finder and Life Investigation For Enceladus). In 2007, the European Space Agency (ESA) proposed sending a probe to Enceladus in a mission to be combined with studies of Titan – known as TandEM (Titan and Enceladus Mission).

Additionally, there’s the Titan Saturn System Mission (TSSM), a joint NASA/ESA flagship-class proposal to explore Saturn’s moons (with a focus on Enceladus). TSSM was competing against the Europa Jupiter System Mission (EJSM) proposal for funding. In February 2009, it was announced that NASA/ESA had given the EJSM mission priority ahead of TSSM, although TSSM will continue to be studied and evaluated.

Enceladus is a tempting target for future research and exploration, and for good reason. For starters, it is one of the few Solar System bodies (alongside with Earth, Io, and Triton) to have confirmed contemporary volcanic activity. Second is the distinct possibility that life exists beneath its icy surface, much like Europa. But with Enceladus, getting to a place where we could study that life would be much easier.

As such, it is almost certain that any missions to Saturn and/or the outer Solar System in the coming years will likely involve a close flyby of Enceladus. Maybe we’ll even pop in a lander and an aquatic explorer to examine the surface and peak underneath it!

We’ve written many articles about Enceladus for Universe Today. Here’s an article about salt found in the plumes from Enceladus, and the possibility of a liquid ocean on Enceladus.

And here is a rundown of Cassini’s Most Interesting Discoveries.

If you’d like more information on Enceladus, check out NASA’s Solar System Exploration Guide, and here’s a link to a cool mosaic image of Enceladus.

We’ve recorded an episode of Astronomy Cast all about Saturn’s moons. Listen here, Episode 61: Saturn’s Moons.

Sources: