Uranus, which takes its name from the Greek God of the sky, is a gas giant and the seventh planet from our Sun. It is also the third largest planet in our Solar System, ranking behind Jupiter and Saturn. Like its fellow gas giants, it has many moons, a ring system, and is primarily composed of gases that are believed to surround a solid core.

Though it can be seen with the naked eye, the realization that Uranus is a planet was a relatively recent one. Though there are indications that it was spotted several times over the course of the past two thousands years, it was not until the 18th century that it was recognized for what it was. Since that time, the full-extent of the planet’s moons, ring system, and mysterious nature have come to be known.

Discovery and Naming:

Like the five classic planets – Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn – Uranus can be seen without the aid of a telescope. But due to its dimness and slow orbit, ancient astronomers believed it to be a star. The earliest known observation was performed by Hipparchos, who recorded it as a star in his star catalog in 128 BCE – observations which were later included in Ptolemy’s Almagest.

The earliest definite sighting of Uranus took place in 1690 when English astronomer John Flamsteed – the first Astronomer Royal – spotted it at least six times and cataloged it as a star (34 Tauri). The French astronomer Pierre Lemonnier also observed it at least twelve times between the years of 1750 and 1769.

However, it was Sir William Herschel’s observation of Uranus on March 13th, 1781, that began the process of identifying it as a planet. At the time, he reported it as a comet sighting, but then engaged in a series of observations using a telescope of his own design to measure its position relative to the stars. When he reported on it to The Royal Society, he claimed it was a comet, but implicitly compared it to a planet.

Afterwards, several astronomers began to explore the possibility that Herschel’s “comet” was in fact a planet. These included Russian astronomer Anders Johan Lexell, who was the first to compute its nearly circular orbit, which led him to conclude it was a planet after all. Berlin astronomer Johann Elert Bode, a member of the “United Astronomical Society”, concurred with this after making similar observations of its orbit.

Soon, Uranus’ status as a planet became a scientific consensus, and by 1783, Herschel himself acknowledged this to the Royal Society. In recognition of his discovery, King George III of England gave Herschel an annual stipend of £200 on condition that he move to Windsor so that the Royal Family could look through his telescopes.

In honor of his new patron, William Herschel decided to name his discovery Georgium Sidus (“George’s Star” or “Georges Planet”). Outside of Britain, this name was not popular, and alternatives were soon proposed. These included French astronomer Jerome Lalande proposing to call it Hershel in honor of its discovery, and Swedish astronomer Erik Prosperin proposing the name Neptune.

Johann Elert Bode proposed the name Uranus, the Latinized version of the Greek god of the sky, Ouranos. This name seemed appropriate, given that Saturn was named after the mythical father of Jupiter, so this new planet should be named after the mythical father of Saturn. Ultimately, Bode’s suggestion became the most widely used and became universal by 1850.

Uranus’ Size, Mass and Orbit:

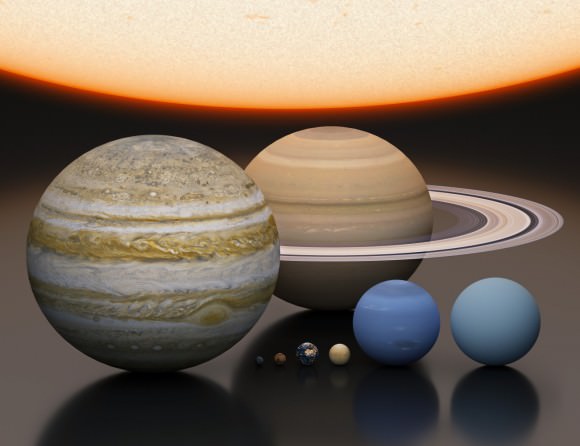

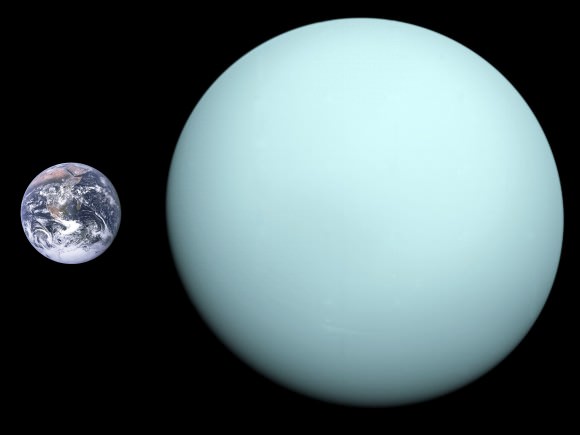

With a mean radius of approximately 25,360 km, a volume of 6.833×1013 km3, and a mass of 8.68 × 1025 kg, Uranus is approximately 4 times the sizes of Earth and 63 times its volume. However, as a gas giant, its density (1.27 g/cm3) is significantly lower; hence, it is only 14.5 as massive as Earth. Its low density also means that while it is the third largest of the gas giants, it is the least massive (falling behind Neptune by 2.6 Earth masses).

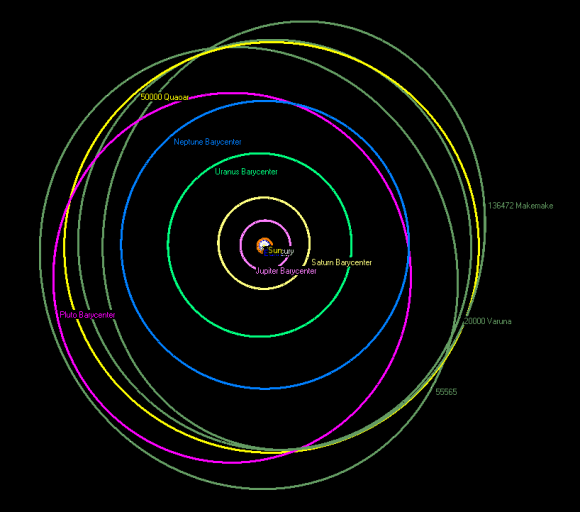

The variation of Uranus’ distance from the Sun is also greater than that any other planet (not including dwarf planets or plutoids). Essentially, the gas giant’s distance from the Sun varies from 18.28 AU (2,735,118,100 km) at perihelion to 20.09 AU (3,006,224,700 km) at aphelion. At an average distance of 3 billion km from the Sun, it takes Uranus roughly 84 years (or 30,687 days) to complete a single orbit of the Sun.

The rotational period of the interior of Uranus is 17 hours, 14 minutes. As with all giant planets, its upper atmosphere experiences strong winds in the direction of rotation. At some latitudes, such as about 60 degrees south, visible features of the atmosphere move much faster, making a full rotation in as little as 14 hours.

One unique feature of Uranus is that it rotates on its side. Whereas all of the Solar System’s planets are tilted on their axes to some degree, Uranus has the most extreme axial tilt of 98°. This leads to the radical seasons that the planet experiences, not to mention an unusual day-night cycle at the poles. At the equator, Uranus experiences normal days and nights; but at the poles, each experience 42 Earth years of day followed by 42 years of night.

Uranus’ Composition:

The standard model of Uranus’s structure is that it consists of three layers: a rocky (silicate/iron–nickel) core in the center, an icy mantle in the middle and an outer envelope of gaseous hydrogen and helium. Much like Jupiter and Saturn, hydrogen and helium account for the majority of the atmosphere – approximately 83% and 15% – but only a small portion of the planet’s overall mass (0.5 to 1.5 Earth masses).

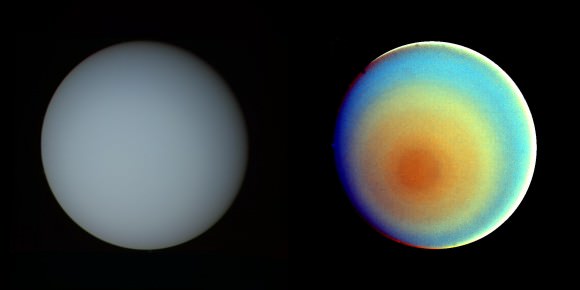

The third most abundant element is methane ice (CH4), which accounts for 2.3% of its composition and which accounts for the planet’s aquamarine or cyan coloring. Trace amounts of various hydrocarbons are also found in the stratosphere of Uranus, which are thought to be produced from methane and ultraviolent radiation-induced photolysis. They include ethane (C2H6), acetylene (C2H2), methylacetylene (CH3C2H), and diacetylene (C2HC2H).

In addition, spectroscopy has uncovered carbon monoxide and carbon dioxide in Uranus’ upper atmosphere, as well as the presence icy clouds of water vapor and other volatiles, such as ammonia and hydrogen sulfide. Because of this, Uranus and Neptune are considered a distinct class of giant planet – known as “Ice Giants” – since they are composed mainly of heavier volatile substances.

The ice mantle is not in fact composed of ice in the conventional sense, but of a hot and dense fluid consisting of water, ammonia and other volatiles. This fluid, which has a high electrical conductivity, is sometimes called a water–ammonia ocean.

The core of Uranus is relatively small, with a mass of only 0.55 Earth masses and a radius that is less than 20% of the planet’s overall size. The mantle comprises its bulk, with around 13.4 Earth masses, and the upper atmosphere is relatively insubstantial, weighing about 0.5 Earth masses and extending for the last 20% of Uranus’s radius.

Uranus’s core density is estimated to be 9 g/cm3, with a pressure in the center of 8 million bars (800 GPa) and a temperature of about 5000 K (which is comparable to the surface of the Sun).

Uranus’ Atmosphere:

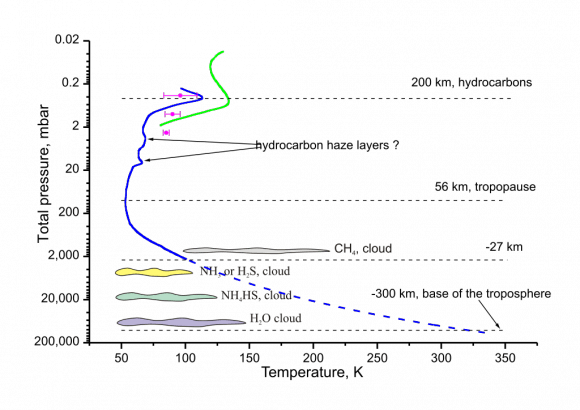

As with Earth, the atmosphere of Uranus is broken into layers, depending upon temperature and pressure. Like the other gas giants, the planet doesn’t have a firm surface, and scientists define the surface as the region where the atmospheric pressure exceeds one bar (the pressure found on Earth at sea level). Anything accessible to remote-sensing capability – which extends down to roughly 300 km below the 1 bar level – is also considered to be the atmosphere.

Using these references points, Uranus’ atmosphere can be divided into three layers. The first is the troposphere, between altitudes of -300 km below the surface and 50 km above it, where pressures range from 100 to 0.1 bar (10 MPa to 10 kPa). The second layer is the stratosphere, which reaches between 50 and 4000 km and experiences pressures between 0.1 and 10-10 bar (10 kPa to 10 µPa).

The troposphere is the densest layer in Uranus’ atmosphere. Here, the temperature ranges from 320 K (46.85 °C/116 °F) at the base (-300 km) to 53 K (-220 °C/-364 °F) at 50 km, with the upper region being the coldest in the solar system. The tropopause region is responsible for the vast majority of Uranus’s thermal infrared emissions, thus determining its effective temperature of 59.1 ± 0.3 K.

Within the troposphere are layers of clouds – water clouds at the lowest pressures, with ammonium hydrosulfide clouds above them. Ammonia and hydrogen sulfide clouds come next. Finally, thin methane clouds lay on the top.

In the stratosphere, temperatures range from 53 K (-220 °C/-364 °F) at the upper level to between 800 and 850 K (527 – 577 °C/980 – 1070 °F) at the base of the thermosphere, thanks largely to heating caused by solar radiation. The stratosphere contains ethane smog, which may contribute to the planet’s dull appearance. Acetylene and methane are also present, and these hazes help warm the stratosphere.

The outermost layer, the thermosphere and corona, extend from 4,000 km to as high as 50,000 km from the surface. This region has a uniform temperature of 800-850 (577 °C/1,070 °F), although scientists are unsure as to the reason. Because the distance to Uranus from the Sun is so great, the amount of heat coming from it is insufficient to generate such high temperatures.

Like Jupiter and Saturn, Uranus’s weather follows a similar pattern where systems are broken up into bands that rotate around the planet, which are driven by internal heat rising to the upper atmosphere. As a result, winds on Uranus can reach up to 900 km/h (560 mph), creating massive storms like the one spotted by the Hubble Space Telescope in 2012. Similar to Jupiter’s Great Red Spot, this “Dark Spot” was a giant cloud vortex that measured 1,700 kilometers by 3,000 kilometers (1,100 miles by 1,900 miles).

Uranus’ Moons:

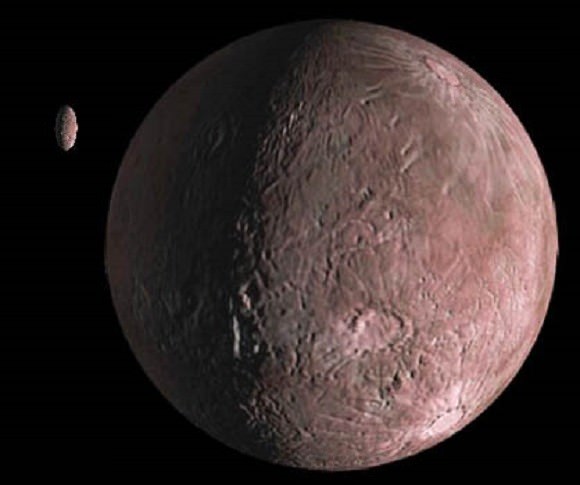

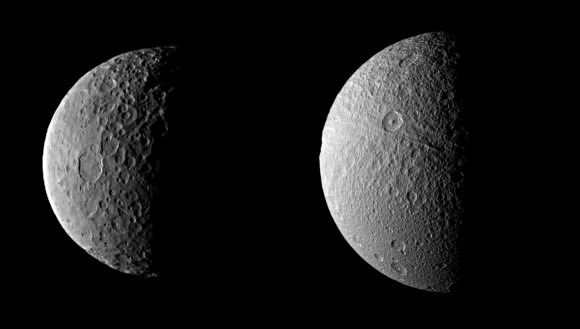

Uranus has 27 known satellites, which are divided into the categories of larger moons, inner moons, and irregular moons (similar to other gas giants). The largest moons of Uranus are, in order of size, Miranda, Ariel, Umbriel, Oberon and Titania. These moons range in diameter and mass from 472 km and 6.7 × 1019 kg for Miranda to 1578 km and 3.5 × 1021 kg for Titania. Each of these moons is particularly dark, with low bond and geometric albedos. Ariel is the brightest while Umbriel is the darkest.

All of the large moons of Uranus are believed to have formed in the accretion disc, which existed around Uranus for some time after its formation, or resulted from the large impact suffered by Uranus early in its history. Each one is comprised of roughly equal amounts of rock and ice, except for Miranda which is made primarily of ice.

The ice component may include ammonia and carbon dioxide, while the rocky material is believed to be composed of carbonaceous material, including organic compounds (similar to asteroids and comets). Their compositions are believed to be differentiated, with an icy mantle surrounding a rocky core.

In the case of Titania and Oberon, it is believed that liquid water oceans may exist at the core/mantle boundary. Their surfaces are also heavily cratered; but in each case, endogenic resurfacing has led to a degree of renewal of their features. Ariel appears to have the youngest surface with the fewest impact craters while Umbriel appears to be the the oldest and most cratered.

The major moons of Uranus have no discernible atmosphere. Also, because of their orbit around Uranus, they experience extreme seasonal cycles. Because Uranus orbits the Sun almost on its side, and the large moons all orbit around Uranus’ equatorial plane, the northern and southern hemispheres experience prolonged periods of daytime and nighttime (42 years at a time).

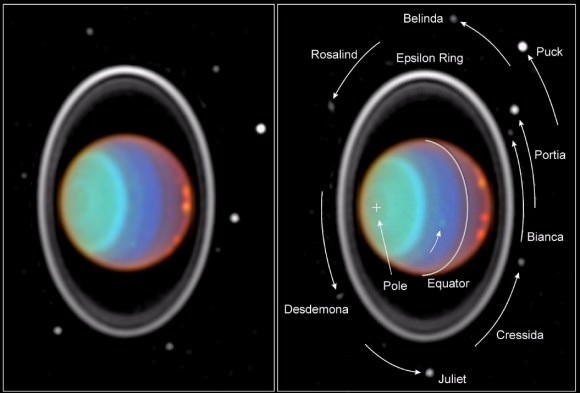

As of 2008, Uranus is known to possess 13 inner moons whose orbits lie inside that of Miranda. They are, in order of distance from the planet: Cordelia, Ophelia, Bianca, Cressida, Desdemona, Juliet, Portia, Rosalind, Cupid, Belinda, Perdita, Puck and Mab. Consistent with the naming of the Uranus’ larger moons, all are named after characters from Shakespearean plays.

All inner moons are intimately connected to Uranus’ ring system, which probably resulted from the fragmentation of one or several small inner moons. Puck, at 162 km, is the largest of the inner moons of Uranus – and the only one imaged by Voyager 2 in any detail – while Puck and Mab are the two outermost inner satellites of Uranus.

All inner moons are dark objects. They are made of water ice contaminated with a dark material, which is probably organic materials processed by Uranus’ radiation. The system is also chaotic and apparently unstable. Computer simulations estimate that collisions may occur, particularly between Desdemona and Cressida or Juliet within the next 100 million years.

As of 2005, Uranus is also known to have nine irregular moons, which orbit it at a distance much greater than that of Oberon. All the irregular moons are probably captured objects that were trapped by Uranus soon after its formation. They are, in order of distance from Uranus: Francisco, Caliban, Stephano, Trincutio, Sycorax, Margaret, Prospero, Setebos, and Ferdinard (once again, named for characters in Shakespearean plays).

Uranus’s irregular moons range in size from about 150 km (Sycorax) to 18 km (Trinculo). With the exception of Margaret, all circle Uranus in retrograde orbits (meaning they orbit the planet in the opposite direction of its spin).

Uranus’ Ring System:

Like Saturn and Jupiter, Uranus has a ring system. However, these rings are composed of extremely dark particles which vary in size from micrometers to a fraction of a meter – hence why they are not nearly as discernible as Saturn’s. Thirteen distinct rings are presently known, the brightest being the epsilon ring. And with the exception of two very narrow ones, these rings usually measure a few kilometers in width.

The rings are probably quite young, and are not believed to have formed with Uranus. The matter in the rings may once have been part of a moon (or moons) that was shattered by high-speed impacts. From numerous pieces of debris that formed as a result of those impacts, only a few particles survived, in stable zones corresponding to the locations of the present rings.

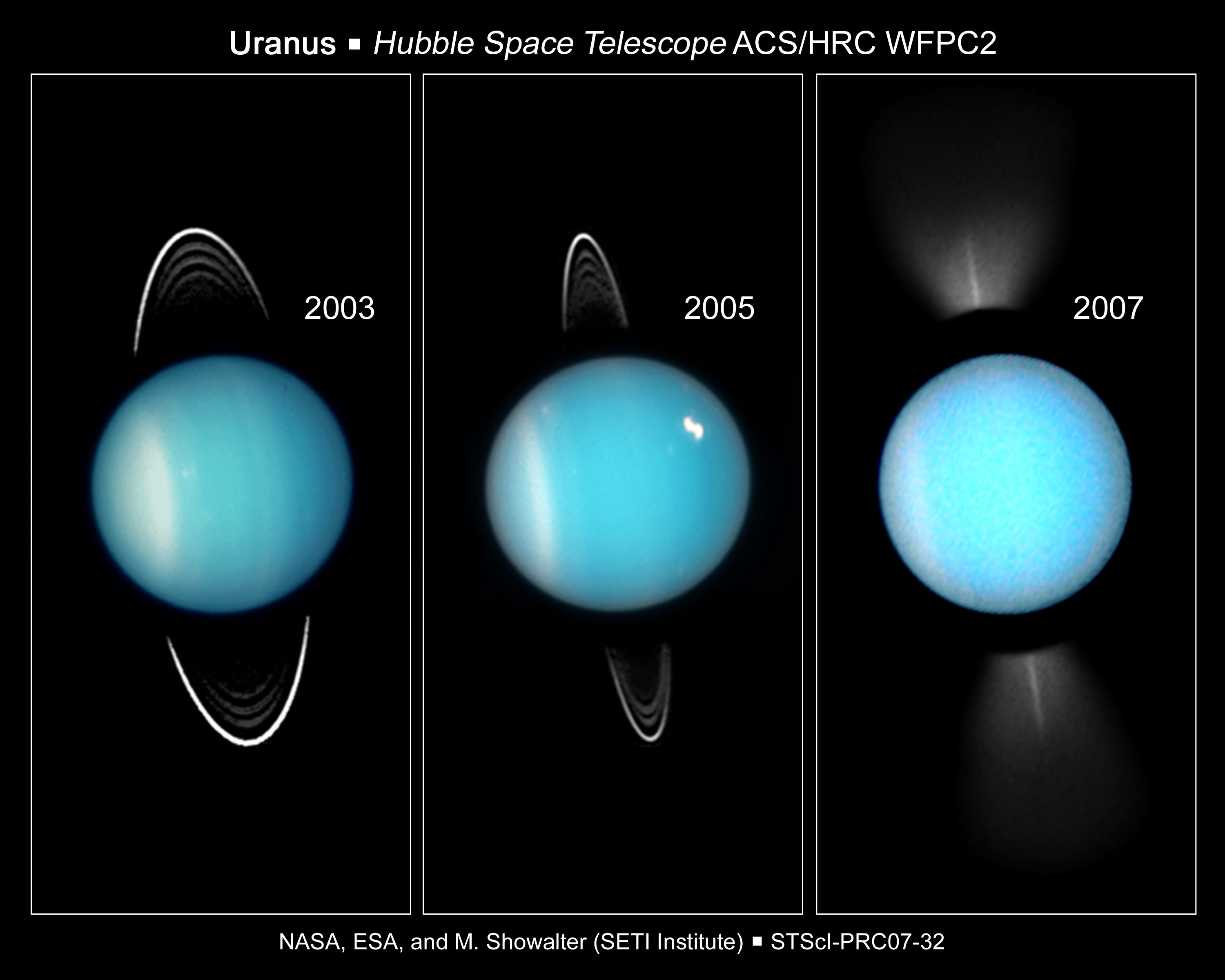

The earliest known observations of the ring system took place on March 10th, 1977, by James L. Elliot, Edward W. Dunham, and Jessica Mink using the Kuiper Airborne Observatory. During an occultation of the star SAO 158687 (also known as HD 128598), they discerned five rings existing within a system around the planet, and observed four more later.

The rings were directly imaged when Voyager 2 passed Uranus in 1986, and the probe was able to detect two additional faint rings – bringing the number of observed rings to 11. In December 2005, the Hubble Space Telescope detected a pair of previously unknown rings, bringing the total to 13. The largest is located twice as far from Uranus as the previously known rings, hence why they are called the “outer” ring system.

In April 2006, images of the new rings from the Keck Observatory yielded the colors of the outer rings: the outermost is blue and the other one red. In contrast, Uranus’s inner rings appear grey. One hypothesis concerning the outer ring’s blue color is that it is composed of minute particles of water ice from the surface of Mab that are small enough to scatter blue light.

Exploration:

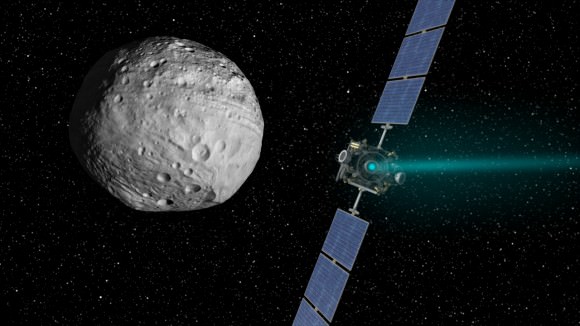

Uranus has only been visited once by any spacecraft: NASA’s Voyager 2 space probe, which flew past the planet in 1986. On January 24th, 1986, Voyager 2 passed within 81,500 km of the surface of the planet, sending back the only close up pictures ever taken of Uranus. Voyager 2 then continued on to make a close encounter with Neptune in 1989.

The possibility of sending the Cassini spacecraft from Saturn to Uranus was evaluated during a mission extension planning phase in 2009. However, this never came to fruition, as it would have taken about twenty years for Cassini to get to the Uranian system after departing Saturn.

In terms of future missions, multiple proposals have been made. For instance, a Uranus orbiter and probe was recommended by the 2013–2022 Planetary Science Decadal Survey published in 2011. This proposal envisaged a launch taking place between 2020–2023 and a 13-year cruise to Uranus. A New Frontiers Uranus Orbiter has been evaluated and was recommended in the study, The Case for a Uranus Orbiter. However, this mission is considered to be lower-priority than future missions to Mars and the Jovian System.

Scientists from the Mullard Space Science Laboratory in the United Kingdom have proposed a joint NASA-ESA mission to Uranus known as Uranus Pathfinder. This mission would involve launching a medium-class mission by 2022, and estimates place its cost at €470 million (~$525 million USD).

Another mission to Uranus, called Herschel Orbital Reconnaissance of the Uranian System (HORUS), was designed by the Applied Physics Laboratory of Johns Hopkins University. The proposal is for a nuclear-powered orbiter carrying a set of instruments, including an imaging camera, spectrometers and a magnetometer. The mission would launch in April 2021 and arrive at Uranus 17 years later.

In 2009, a team of planetary scientists from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory advanced possible designs for a solar-powered Uranus orbiter. The most favorable launch window for such a probe would be in August 2018, with arrival at Uranus in September 2030. The science package may include magnetometers, particle detectors and, possibly, an imaging camera.

Suffice it to say, Uranus is a hard target when it comes to exploration, and its distance has made the process of observing it recognizing it for what it was problematic in the past. And in the future, with most of our mission focused on exploring Mars, Europa, and Near-Earth Asteroids, the prospect of a mission to this region of the Solar System doesn’t seem very likely.

But budget environments change, as do scientific priorities. And with interest in the Kuiper Belt exploding thanks to the discovery of many Trans-Neptunian Objects in recent years, it is entirely possible that scientists will demand that a mission to the out solar system be mounted. If and when one occurs, it may be possible to have the probe swing by Uranus on its way out, gathering information and pictures to help advance our understanding of this “Ice Giant”.

We have many interesting articles about Uranus here at Universe Today. We hope you find what you are looking for in the list below:

- Atmosphere of Uranus

- Color of Uranus

- What is Uranus Made Of?

- How Long is a Day on Uranus?

- Density of Uranus

- Diameter of Uranus

- Discovery of Uranus

- How Far is Uranus from Earth?

- How Should You Pronounce Uranus?

- Gravity on Uranus

- Size of Uranus

- Tilt of Uranus

- Name of Uranus

- Mass of Uranus

- Uranus Pictures

- How Long is Year on Uranus?

- Orbit of Uranus

- Weather on Uranus

- Radius of Uranus

- Surface of Uranus

- Symbol for Uranus

- Core of Uranus

- 10 Interesting Facts About Uranus

- Temperature of Uranus

- Life on Uranus

- Uranus Rings

- Seasons on Uranus

- Water on Uranus

- Uranus Moons

- How Many Moons Does Uranus Have?

- Uranus and Neptune

- How Many Rings Does Uranus Have?

- How Long Does it Take Uranus to Orbit the Sun?

- Uranus Distance from the Sun

- Who Discovered Uranus?

- When was Uranus Discovered?

- Uranus Fact Sheet

- Moons of Uranus

- Oberon

- Titania

- Umbriel

- Who Discovered Uranus and When?