Boy, how about that total solar eclipse last Friday? And there’s more in store, as most of North America will be treated to yet another total lunar eclipse on the morning of April 4th. This eclipse is member three of four of a quartet of lunar eclipses, known as a tetrad.

Solar and lunar eclipses are predictable, and serve as a dramatic reminder of the clockwork nature of the universe. Many will marvel at the ‘perfect symmetry’ of eclipses as seen from the Earth, though the true picture is much more complex. Yes, the Sun is roughly 400 times larger in diameter than the Moon, but also about 400 times farther away. This distance isn’t always constant, however, as the orbits of both the Earth and Moon are elliptical. And to complicate matters, the Moon is currently moving 3 to 4 centimetres farther away from the Earth per year. Already, annular eclipses are more common in the current epoch than are total solar eclipses, and about 1.4 billion years from now, total solar eclipses will cease to happen entirely.

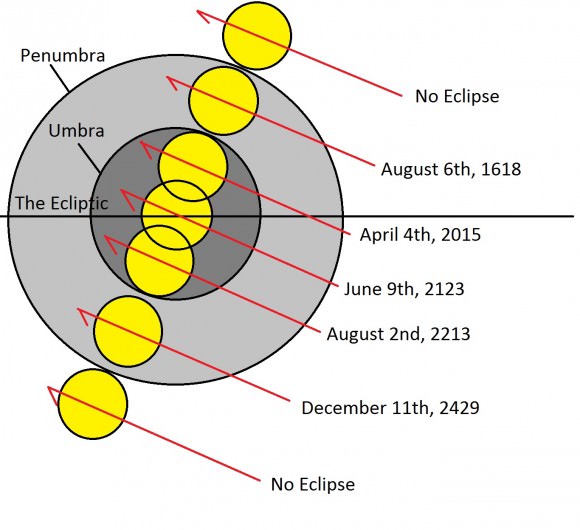

This has an impact on lunar eclipses as well. The dark inner umbra of the Earth is an average of about 1.25 degrees across at the distance from Earth to the Moon. The Moon’s orbit is inclined 5.1 degrees relative to the ecliptic plane, which traces out the Earth’s path around the Sun. If this inclination was equal to zero, we’d be treated to two eclipses — one solar and one lunar — every 29.5 day synodic month.

This inclination assures that we have, on average, two eclipse seasons year, and that eclipses occur in groupings of 2-3. The maximum number of eclipses that can occur in a calendar year is 7, which next occurs in 2038, and the minimum is 4, as occurs in 2015.

A solar eclipse occurs at New Moon, and a lunar eclipse always occurs at Full — a fact that many works of film and fiction famously get wrong. And while you have to happen to be in the narrow path of a solar eclipse to witness totality, the whole Moonward facing hemisphere of the Earth gets to witness a lunar eclipse. Ancient cultures recognized the mathematical vagaries of the lunar and solar cycles as they attempted to reconcile early calendars. Our modern Gregorian calendar strikes a balance between the solar mean and tropical year. The Muslim calendar uses strictly lunar periods, and thus falls 11 days short of a 365 day year. The Jewish and Chinese calendars incorporate a hybrid luni-solar system, assuring that an intercalculary ‘leap month’ needs to be added every few years.

But trace out the solar and lunar cycles far enough, and something neat happens. Meton of Athens discovered in the 5th century BC that 235 synodic periods very nearly equals 19 solar years to within a few hours. This means that the phases of the Moon ‘sync up’ every 19-year Metonic cycle, handy if you’re say, trying to calculate the future dates for a movable feast such as Easter, which falls on (deep breath) the first Sunday after the first Full Moon after the March equinox.

But there’s more. Take a period of 223 synodic months, and they sync up three key lunar cycles which are crucial to predicting eclipses;

Synodic month- The time it takes for the Moon to return to like phase (29.5 days).

Anomalistic month- The time it takes for the Moon to return to perigee (27.6 days).

Draconic month- the time it takes for the Moon to return to a similar intersecting node (ascending or descending) along the ecliptic (27.2 days).

That last one is crucial, as eclipses always occur when the Moon is near a node. For example, the Moon crosses ascending node less than six hours prior to the start of the April 4th lunar eclipse.

And thus, the saros was born. A saros period is just eight hours shy of 18 years and 11 days, which in turn is equal to 223 synodic, 242 anomalistic or 239 draconic months.

The name saros was first described by Edmond Halley in 1691, who took it from a translation of an 11th century Byzantine dictionary. The plural of saros is saroses.

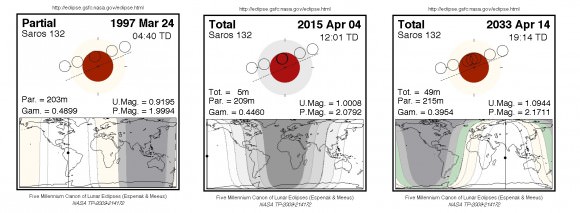

This also means that solar and lunar eclipses one saros period apart share nearly the same geometry, shifted 120 degrees in longitude westward. For example, the April 4th lunar eclipse is member number 30 in a cycle of 71 lunar eclipses belonging to saros series 132. A similar eclipse occurred one saros ago on March 24th, 1997. Stick around until April 14th, 2033 and you’ll complete a personal triple saros of eclipses, known as an exeligmos.

Dozens of saros series — both solar and lunar — are underway at any particular time.

But there’s something else unique about April’s eclipse. Though saros 132 started with a slim shallow penumbral eclipse way back on May 12th, 1492, this upcoming eclipse features the very first total lunar eclipse of the series. You can tell, as the duration of totality is a short 4 minutes and 43 seconds, a far cry from the maximum duration of 107 minutes that can occur during a central eclipse.

This particular saros cycle of eclipses will continue to become more central as time goes on. The final total lunar eclipse of the series occurs on August 2nd, 2213 AD, and the saros finally ends way out on June 26th, 2754.

Eclipses, both lunar and solar, have also made their way into the annuals of history. A rising partial eclipse greeted the defenders of Constantinople in 1453, fulfilling a prophecy in the mind of the superstitious when the city fell to the Ottoman Turks seven days later. And you’d think we’d know better by now, but modern day fears of the ‘Blood Moon‘ seen during an eclipse still swirl around the internet even today. Lunar eclipses even helped mariners get a onetime fix on longitude at sea: Christopher Columbus and Captain James Cook both employed this method.

All thoughts to ponder as you watch the April 4th total lunar eclipse. This eclipse will be visible for observers across the Pacific, the Asian Far East, Australia and western North America, after which you’ll have one more shot at total lunar eclipse in 2015 on September 28th. The next total lunar eclipse after that won’t be until January 31st 2018, favoring North America.

Welcome to the saros!

Read Dave Dickinson’s eclipse-fueled sci-fi tales Exeligmos and Shadowfall.