Think big. Really big. Like, cosmic big. How big can things in the Universe get? Is a galaxy big? What about a supercluster? What is the biggest thing in the Universe?

Our observable Universe is a sphere 96 billion light-years across, and the entire Universe might be infinite in size. Which is a hoarders dream walk-in closet space stuffed full of “things”. It’s loaded down with so much stuff, we’ve even given up naming things individually and now just spew out a list of letters and numbers to try and keep track of it all.

So, as is traditional, in a fit of adolescent OCD and one-upmanship reserved generally for things like tanks, planes and guns, we’re drawn to the question… What’s the biggest thing in the Universe. Well, 14 year old Fraser Cain, put down your copy of “Weapons and Warfare Volume 3” which you picked up at the dollar store as part of an incomplete set, as this is going to get a little tricky.

It all depends on what you mean by a “thing”. The biggest physical object is probably a star. The largest possible red giant star could be as big as 2,100 times the size our Sun. Placed inside our own Solar System, a monster star like this would extend out past the orbit of Saturn. That’s big, but we might be able to get even bigger if we’re willing to get past the idea that a “thing” has to be a homogeneous physical object.

Consider the regions around supermassive black holes. Within our own galaxy, things are pretty quiet, but around actively feeding black holes, there can be disks of material with such temperature and density that they act like the core of a star, fusing hydrogen into helium. Which, purely based on high volumetric density of pure awesome, I’m going to call a thing. An accretion disk around a quasar could be light days across, extending well past the orbit of Pluto and killing us all, if you dumped it in our Solar System.

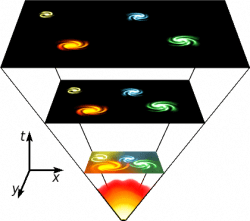

If we’re going to be all philosophical about what constitutes a “thing” and you’re not all fussy about physical structure and just want a collection of material held together by gravity, then we can really can make some leaps and bounds in our “who’s got the biggest” measuring contest. Our own galaxy extends up to 120,000 light-years across.

There are much larger galaxies, ones that make the Milky Way look like that cat leash pendant from Men In Black 2. And ours is just one contained within a much larger cluster of galaxies known, rather unimaginatively, as the Local Group. Don’t let the centrist name fool you, this cluster contains around 50 galaxies and measures more than 10 million light-years across.

And we’re just getting started. The Local Group is one part of the Virgo Supercluster. A massive galactic structure that measures 110 million light-years apart. In 2014, astronomers announced that the Virgo Supercluster is just one lobe of an even larger structure, beautifully known as Laniakea, or “Immeasurable heaven” in Hawaiian. The name originated from Nawa’a Napoleon, an associate professor of Hawaiian Language at Kapiolani Community College. It honors the Polynesian sailors using “heavenly knowledge” navigating the Pacific Ocean, reminding us that romance is still alive and well in space and astronomy. Laniakea is centered around the Great Attractor – a mysterious source of gravity drawing galaxies towards it.

I almost forgot about our size contest. So who’s got the biggest space thing? According to buzzkill Ethan Siegel from the Starts With a Bang blog, you can’t actually have a structure that’s as big as Laniakea, and call it a thing. The fine-print reality is that the expansion of the Universe is being accelerated by dark energy. These galaxies are being pushed apart by dark energy faster than gravity can pull them together. So they’d never be able to form into a single object given enough time.

In other words, the largest possible object is a collection of galaxies at the exact size where gravity is just strong enough to overcome the expansive force of dark energy. Beyond that, everything’s getting spread apart, and it’s for our purposes we’re actually going to draw a line and say it’s not quite right to call it a thing. Unless you’d suggest a giant expanse of nothing is a thing… but let’s save that for another episode.

So what do you think? Do you feel like it’s right to call superclusters like Laniakea “a structure”?