Rockets are the perfect way to get around in space. But how do they work?

Space travel and rockets, it’s like ice cream and apple pie, or ice cream and apple pie and my face. They just go together. They belong together.

But what if I’m allergic to rockets, or have some kind of cylindrical intolerance, or flaming column sensitivity that makes me hive out? Why can’t I fly to space in balloons or airplanes or helicopters? Why do we need these pointy cubist eggplant flame tubes?

The space age followed the development of powerful V2 rockets in WW II. They could hit targets 320 km away and reach an altitude of 200 km. They were a new kind of war machine, a terrifying weapon that could hurl payloads of destruction from the skies. But this terrifying development is what brought us our modern rockets as their propulsion system can work up where there’s no air, in the vacuum of space.

How do they actually work? It all comes down to that “every action, equal and opposite reaction” thing that Newton was always going on about.

If you take a balloon, fill it with air, and then let it go. All that air rushing out propels the balloon around. This kind of balloon rocket would work perfectly well in space too although it might be a little too fragile and unpredictable to want to strap yourself to.

If we take that idea and scale it up, add some fuel tanks and fins, attitude control and optionally: astronauts. We’ve got ourselves a rocket. It works by pushing “stuff” out one end of a tube at the highest possible velocity. The faster you can blow stuff out the end, the faster the tube itself is going to go.

This means rocket science is really all about how to get the exhaust gases hurling out the backside of the rocket as quickly and forcefully as possible. The fuel can be solid, like the space shuttle’s solid rocket boosters. Or the fuel can be liquid, like the shuttle’s main fuel tank filled with liquid oxygen and hydrogen.

This fuel is ignited and completely converted into exhaust gases which blast out of the rocket’s nozzles at high velocity. Really, really high velocity.

The scary part for passengers is that modern rockets are mostly made of fuel. In fact, the weight of the space shuttle’s fuel was 20 times more than the weight of the shuttle itself. Which I believe really puts a fine point on the bravery of any astronaut. Think of a rocket as a beer can, filled with explosives, that you strap yourself to the outside of. To make a rocket go faster and shorten the travel time, you want to kick material out at a higher velocity.

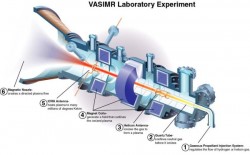

NASA has experimented with ion drives for some of its missions. These highly efficient engines use electric fields to accelerate particles of xenon at much higher velocities. Even though they use a fraction of the amount of fuel, ion engines can reach much higher speeds because of the high exhaust velocity.

And even higher velocity rockets have been tabled, such as the VASIMIR engine and even antimatter engines. So how do rockets work? Just like deflating balloons, only bigger. Much much bigger. And full of explosives and modeled on a horrible and terrifying weapon from the second world war. Really, not much like a balloon at all…

Have you ever made a rocket? What’s your favorite rocketry experiment. Tell us in the comments below.

And if you like what you see, come check out our Patreon page and find out how you can get these videos early while helping us bring you more great content!