When it comes to searching for worlds that could support extra-terrestrial life, scientists currently rely on the “low-hanging fruit” approach. Since we only know of one set of conditions under which life can thrive – i.e. what we have here on Earth – it makes sense to look for worlds that have these same conditions. These include being located within a star’s habitable zone, having a stable atmosphere, and being able to maintain liquid water on the surface.

Until now, scientists have relied on methods that make it very difficult to detect water vapor in the atmosphere’s of terrestrial planets. But thanks to a new study led by Yuka Fujii of NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies (GISS), that may be about to change. Using a new three-dimensional model that takes into account global circulation patterns, this study also indicates that habitable exoplanets may be more common than we thought.

The study, titled “NIR-driven Moist Upper Atmospheres of Synchronously Rotating Temperate Terrestrial Exoplanets“, recently appeared in The Astrophysical Journal. In addition to Dr. Fujii, who is also a member of the Earth-Life Science Institute at the Tokyo Institute of Technology, the research team included Anthony D. Del Genio (GISS) and David S. Amundsen (GISS and Columbia University).

To put it simply, liquid water is essential to life as we know it. If a planet does not have a warm enough atmosphere to maintain liquid water on its surface for a sufficient amount of time (on the order of billions of years), then it is unlikely that life will be able to emerge and evolve. If a planet is too distant from its star, its surface water will freeze; if it is too close, its surface water will evaporate and be lost to space.

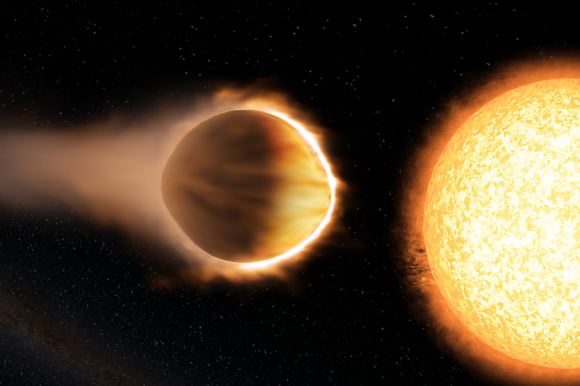

While water has been detected in the atmospheres of exoplanets before, in all cases, the planets were massive gas giants that orbited very closely to their stars. (aka. “Hot Jupiters”). As Fujii and her colleagues state in their study:

“Although H2O signatures have been detected in the atmospheres of hot Jupiters, detecting molecular signatures, including H2O, on temperate terrestrial planets is exceedingly challenging, because of the small planetary radius and the small scale height (due to the lower temperature and presumably larger mean molecular weight).”

When it comes to terrestrial (i.e. rocky) exoplanets, previous studies were forced to rely on one-dimensional models to calculate the presence of water. This consisted of measuring hydrogen loss, where water vapor in the stratosphere is broken down into hydrogen and oxygen from exposure to ultraviolet radiation. By measuring the rate at which hydrogen is lost to space, scientists would estimate the amount of liquid water still present on the surface.

However, as Dr. Fujii and her colleagues explain, such models rely on several assumptions that cannot be addressed, which include the global transport of heat and water vapor vapor, as well as the effects of clouds. Basically, previous models predicted that for water vapor to reach the stratosphere, long-term surface temperatures on these exoplanets would have to be more than 66 °C (150 °F) higher than what we experience here on Earth.

These temperatures could create powerful convective storms on the surface. However, these storms could not be the reason water reaches the stratosphere when it comes to slowly rotating planets entering a moist greenhouse state – where water vapor intensifies heat. Planets that orbit closely to their parent stars are known to either have a slow rotation or to be tidally-locked with their planets, thus making convective storms unlikely.

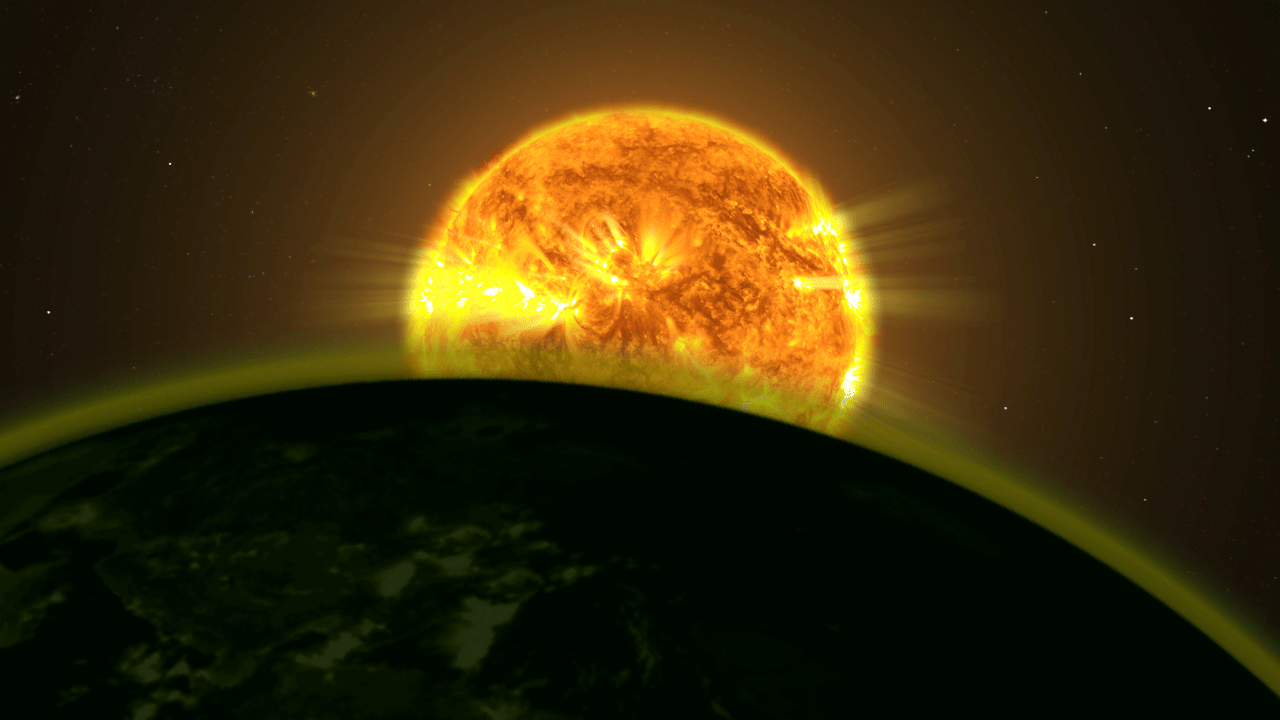

This occurs quite often for terrestrial planets that are located around low-mass, ultra cool, M-type (red dwarf) stars. For these planets, their proximity to their host star means that it’s gravitational influence will be strong enough to slow down or completely arrest their rotation. When this occurs, thick clouds form on the dayside of the planet, protecting it from much of the star’s light.

The team found that, while this could keep the dayside cool and prevent water vapor from rising, the amount of near-Infrared radiation (NIR) could provide enough heat to cause a planet to enter a moist greenhouse state. This is especially true of M-type and other cool dwarf stars, which are known to produce more in the way of NIR. As this radiation warms the clouds, water vapor will rise into the stratosphere.

To address this, Fujii and her team relied on three-dimensional general circulation models (GCMs) which incorporate atmospheric circulation and climate heterogeneity. For the sake of their model, the team started with a planet that had an Earth-like atmosphere and was entirely covered by oceans. This allowed the team to clearly see how variations in distance from different types of stars would effect conditions on the planets surfaces.

These assumptions allowed the team to clearly see how changing the orbital distance and type of stellar radiation affected the amount of water vapor in the stratosphere. As Dr. Fujii explained in a NASA press release:

“Using a model that more realistically simulates atmospheric conditions, we discovered a new process that controls the habitability of exoplanets and will guide us in identifying candidates for further study… We found an important role for the type of radiation a star emits and the effect it has on the atmospheric circulation of an exoplanet in making the moist greenhouse state.”

In the end, the team’s new model demonstrated that since low-mass star emit the bulk of their light at NIR wavelengths, a moist greenhouse state will result for planets orbiting closely to them. This would result in conditions on their surfaces that comparable to what Earth experiences in the tropics, where conditions are hot and moist, instead of hot and dry.

What’s more, their model indicated that NIR-driven processes increased moisture in the stratosphere gradually, to the point that exoplanets orbiting closer to their stars could remain habitable. This new approach to assessing potential habitability will allow astronomers to simulate circulation of planetary atmospheres and the special features of that circulation, which is something one-dimensional models cannot do.

In the future, the team plans to assess how variations in planetary characteristics -such as gravity, size, atmospheric composition, and surface pressure – could affect water vapor circulation and habitability. This will, along with their 3-dimensional model that takes planetary circulation patterns into account, allow astronomers to determine the potential habitability of distant planets with greater accuracy. As Anthony Del Genio indicated:

“As long as we know the temperature of the star, we can estimate whether planets close to their stars have the potential to be in the moist greenhouse state. Current technology will be pushed to the limit to detect small amounts of water vapor in an exoplanet’s atmosphere. If there is enough water to be detected, it probably means that planet is in the moist greenhouse state.”

Beyond offering astronomers a more comprehensive method for determining exoplanet habitability, this study is also good news for exoplanet-hunters hoping to find habitable planets around M-type stars. Low-mass, ultra-cool, M-type stars are the most common star in the Universe, accounting for roughly 75% of all stars in the Milky Way. Knowing that they could support habitable exoplanets greatly increases the odds of find one.

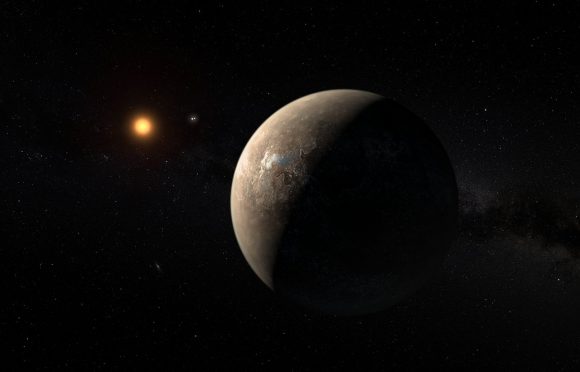

In addition, this study is VERY good news given the recent spate of research that has cast serious doubt on the ability of M-type stars to host habitable planets. This research was conducted in response to the many terrestrial planets that have been discovered around nearby red dwarfs in recent years. What they revealed was that, in general, red dwarf stars experience too much flare and could strip their respective planets of their atmospheres.

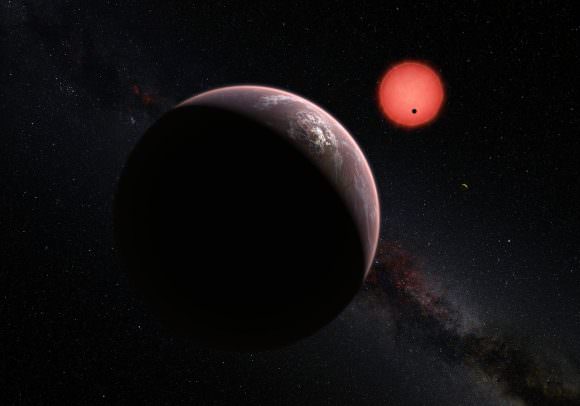

These include the 7-planet TRAPPIST-1 system (three of which are located in the star’s habitable zone) and the closest exoplanet to the Solar System, Proxima b. The sheer number of Earth-like planets discovered around M-type stars, coupled with this class of star’s natural longevity, has led many in the astrophysical community to venture that red dwarf stars might be the most likely place to find habitable exoplanets.

With this latest study, which indicates that these planets could be habitable after all, it would seem that the ball is effectively back in their court!

Further Reading: NASA, The Astrophysical Journal