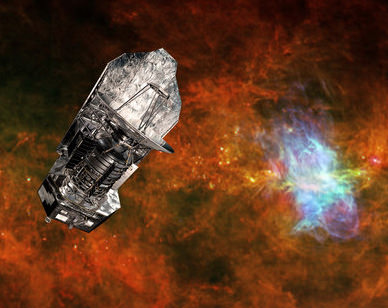

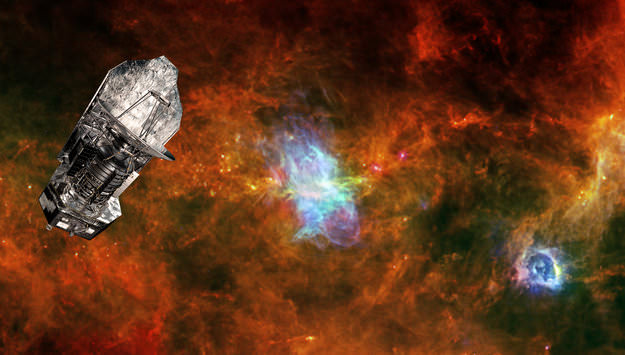

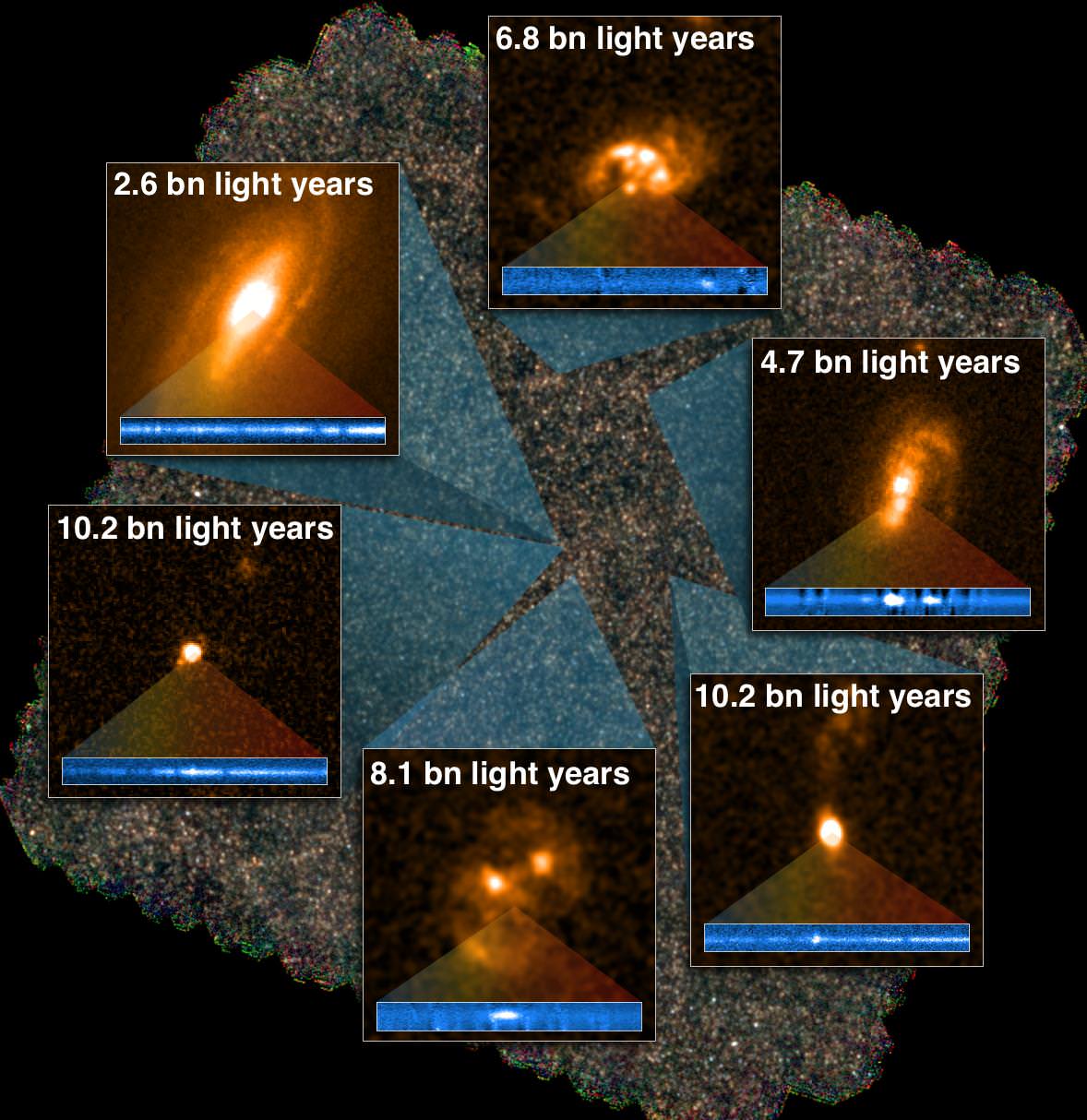

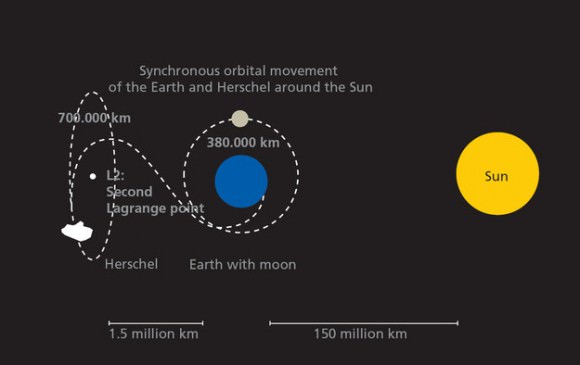

A pair of astronomers has proved that we haven’t seen the last of the Herschel Space Observatory! On June 17, 2013, engineers for the Herschel space telescope sent final commands to put the decommissioned observatory into its “graveyard” heliocentric parking orbit, after the liquid helium that cooled the observatory’s instruments was depleted. Now, Nick Howes and Ernesto Guido from the Remanzacco Observatory have used the 2 meter Faulkes Telescope North in Hawaii to take a picture of the infrared observatory as it is moving away from its orbit around the L2 LaGrange Point where it spent the entirety of its mission.

Howes told Universe Today that their observations not only improve future chances of it being seen, but also will help astronomers in that the observatory won’t be mistaken for a new asteroid.

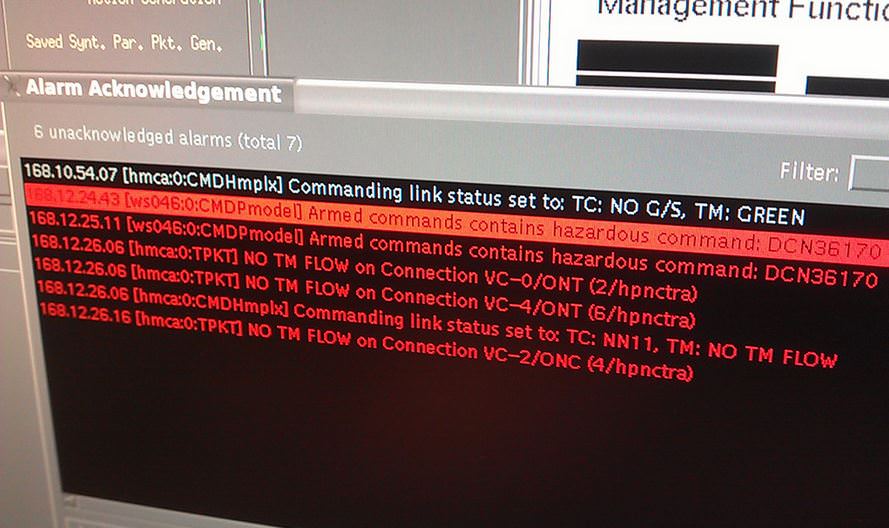

“We saw a potential issue here,” Howes said via email, “as the spacecraft would be in a slow tumble, receding from its stable L2 orbit, subjected to solar radiation pressure. And as ESA’s ground stations were no longer communicating with it, so we wanted to basically check the orbits and make sure that for future science, it was not mistakenly detected as an asteroid.”

When Howes and Guido realized that JPL’s Horizons coordinate system — which generates coordinates for objects in space like Herschel — would be suspending coordinates for the observatory from the end of June, they quickly and urgently used the information they had on Herschel’s movements to make their observations.

“The ephemeris from JPL and the Minor Planet Center varied,” Howes said, “and appeared to show quite different long term positions, so we took the initiative to try to help make sure this orbit was better understood. We knew ESA’s scientists had a pretty good handle on the position, but were perplexed by the variance in the coordinates being generated by the two ephemeris systems”

Radiation pressure and a host of other factors would have and will continue to affect the position of the spacecraft, but with it getting fainter by the day, Howes and Guido made the effort by taking two nights of observations to try and find Herschel as it drifted away from L2.

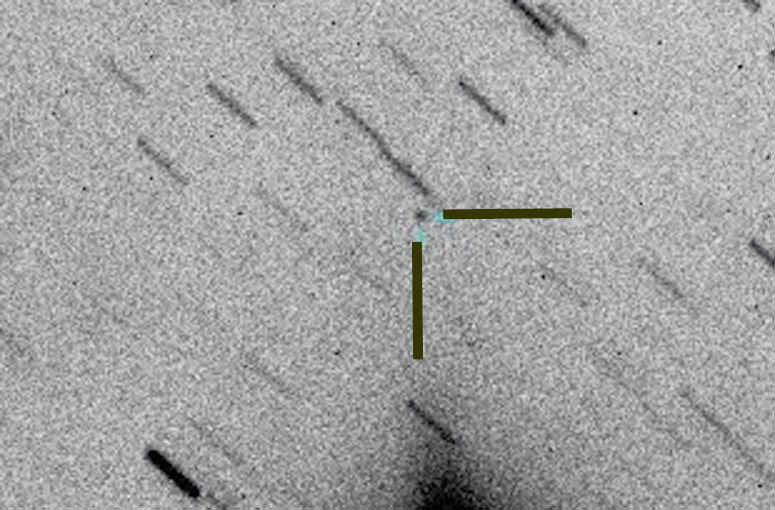

“Imaging a several metre wide spacecraft at over 2.1 million km from Earth in an orbit that was not quite precise, and a tumbling spacecraft is not an easy task, at the faint magnitudes it theoretically could have been at, ” said Guido, who helps manage the Remanzacco Observatory in Italy. “And while we found what we thought could be it on the first night, our calculations would need to be verified by observing it on a second night to validate that it was indeed Herschel.”

Howes, who’d written about Herschel when working in science communications for ESA, contacted several of the mission team via emails, who gave valuable advice on the effects of the final orbital burn.

“We effectively had three possible locations to hunt in,” Howes said, “and luckily, as rain at one of our telescope sites stopped our plans for the third run, and nothing showed up in our first coordinates, we managed to get it in the second set of images, exactly where we thought it could be, with the correct data for its motion, position angle and other orbital characteristics. Ernesto worked on the data reduction for these images, and after about 30 minutes of frantic discussion, said ‘I think I’ve found it.’”

The team have filed their data with the Minor Planet Center, and have worked closely with astronomers at Kitt Peak, who also imaged the Observatory, further refining the observing arc, passing their coordinates even on to astronomers in Chile, with significantly larger telescopes to get even more images of it.

The Faulkes Telescope Project is based at the University of South Wales, and the telescopes are operated by the Las Cumbres Observatory Global Telescope Network. The telescopes are also used for educational purposes, and schools using the Faulkes Telescope will be able to follow Herschel as she leaves her orbit to wander around the Sun. It will return to our neck of the Solar System around 2027/2028 (astrometry measured by Howes and Guido is factoring in radiation pressure, so the values are approximate), when it will return at around magnitude 21.7.

“We’ve engaged schools in this project as it’s great for learning astrometry, and photometry as well as a fun thing to do, and they’ve also been making animations from our data.”

Howes and Guido hope that the updated information will help others keep an eye on the telescope in the future. “It’s been an exciting week, and we wanted to say thank you to ESA for building such a magnificent telescope,” Howes said. “We just wanted to give it a good send off!”