Where will YOU be on August 21st, 2017?

Astronomy is all about humility and thinking big in terms of space and time. It’s routine for astronomers to talk of comets on thousand year orbits, or stars with life spans measured in billions of years…

Yup, the lifespan of your average humanoid is indeed fleeting, and pales in comparison to the universe, that’s for sure. But one astronomical series that you can hope to live through is the cycle of eclipses.

I remember reading about the total solar eclipse of February 26th, 1979 as a kid. Carter was in the White House, KISS was mounting yet another comeback, and Voyager 1 was wowing us with images of Jupiter. That was also the last total solar eclipse to grace mainland United States in the 20th century.

But the ongoing “eclipse-drought” is about to be broken.

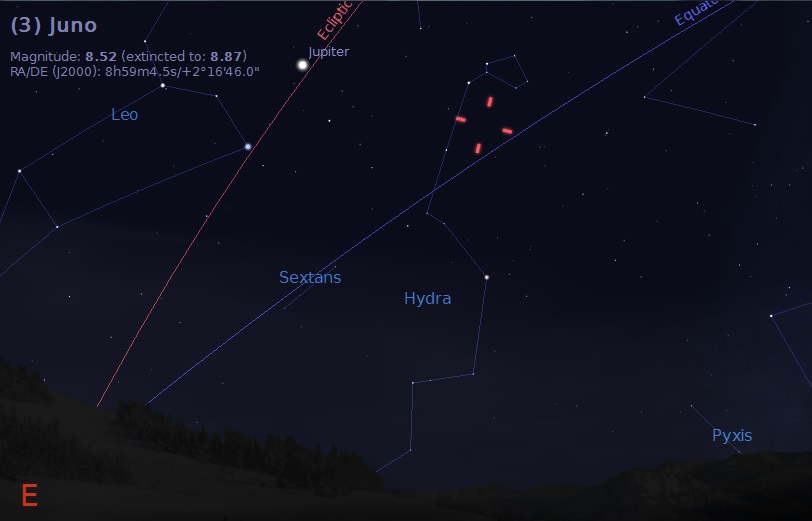

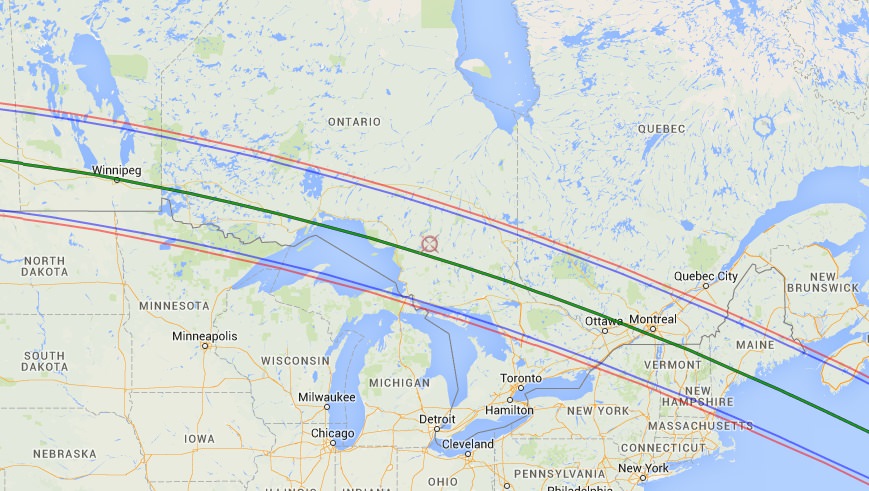

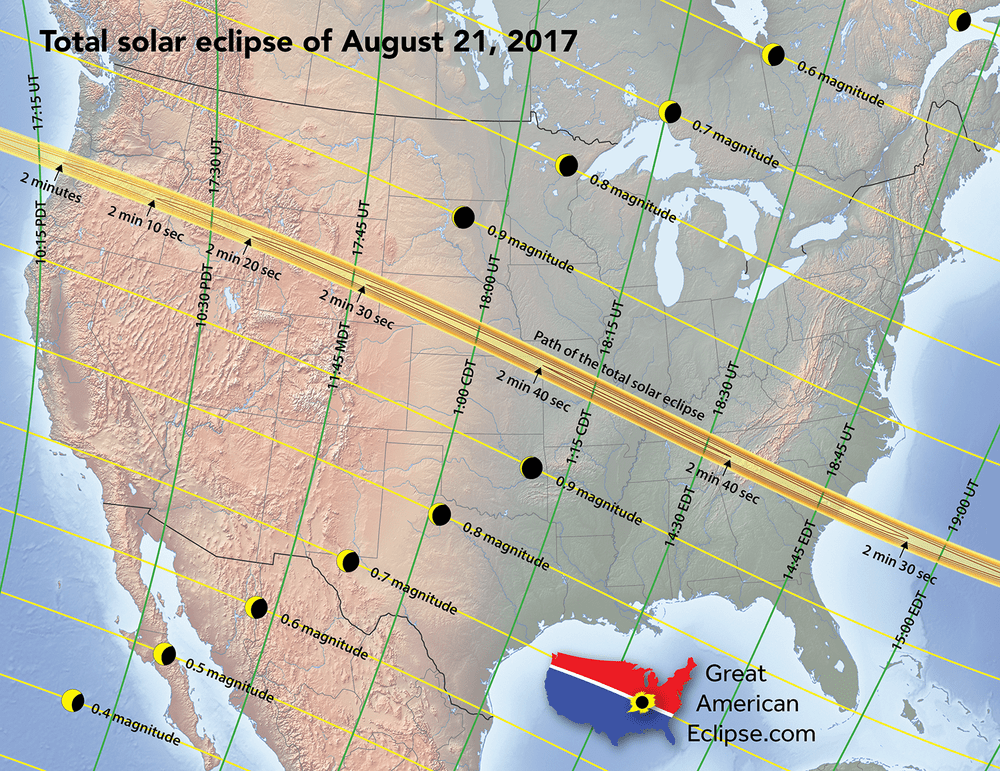

One thousand days from this coming Monday, November 24th on August 21st 2017, the shadow of the Moon will touch down off of the Oregon coast and sweep eastward across the U.S. heartland before heading out to the Atlantic off of the coast of South Carolina. Millions live within a days’ drive of the 115 kilometre wide path, and the eclipse has the added plus of occurring at the tail end of summer vacation season. This also means that lots of folks will be camping and otherwise mobile with their RVs and able to journey to the event.

The Great American Eclipse of 2017 from Michael Zeiler on Vimeo.

This is also the last total solar eclipse to pass over any of the 50 United States since July 11th, 1991, and the first eclipse to cross the contiguous United States from “sea to shining sea” since way back on June 8th, 1918.

Think it’s too early to prepare? Towns across the path, including Hopkinsville, Kentucky and towns in Kansas and Nebraska are already laying plans for eclipse day. Other major U.S. cities, such as Nashville, Idaho Falls, and Columbia, South Carolina also lie along the path of totality, and the spectacle promises to spawn a whole new generation of “umbraphiles” or eclipse chasers.

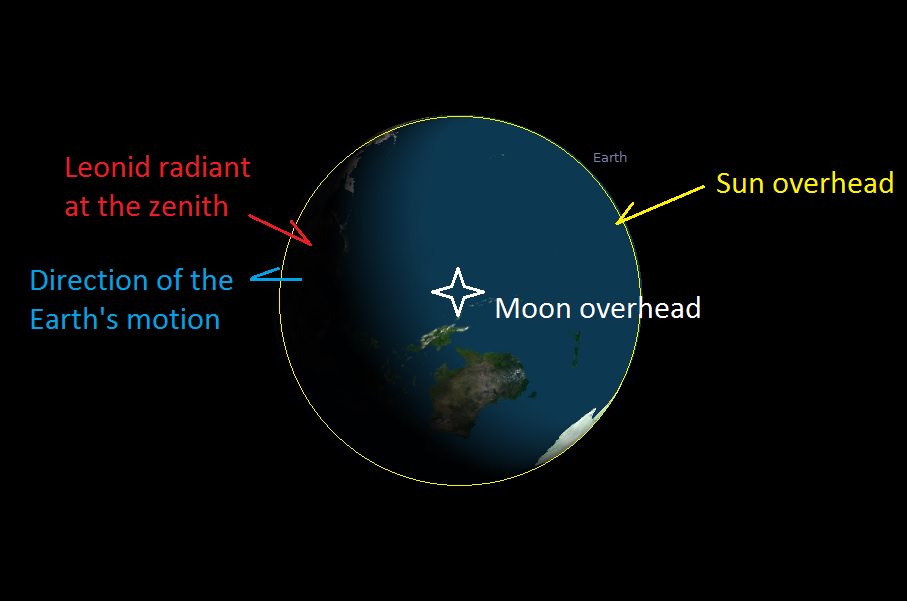

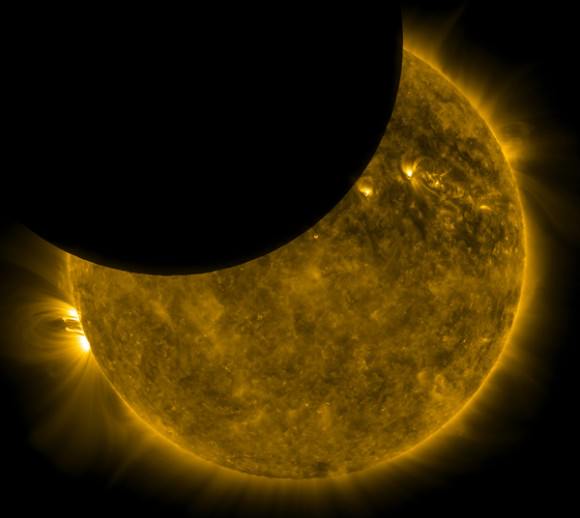

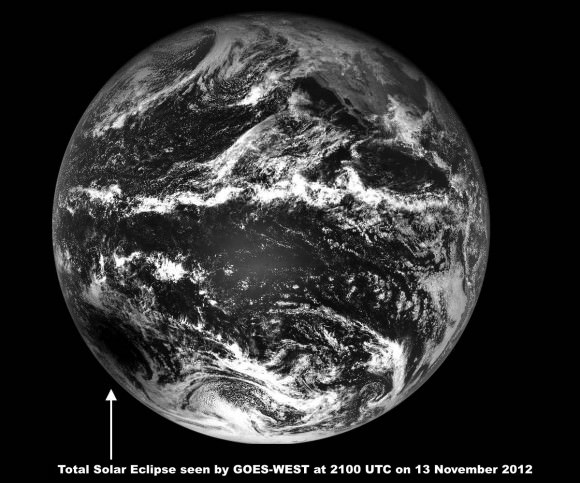

A total solar eclipse is an unforgettable sight. But unlike a total lunar eclipse, which can be viewed from the moonward-facing hemisphere of the Earth, one generally has to journey to the narrow path of totality to see a total solar eclipse. Totality rarely comes to you.

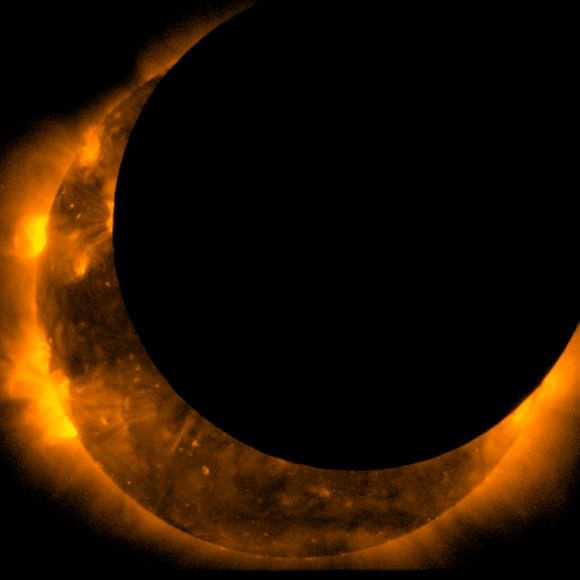

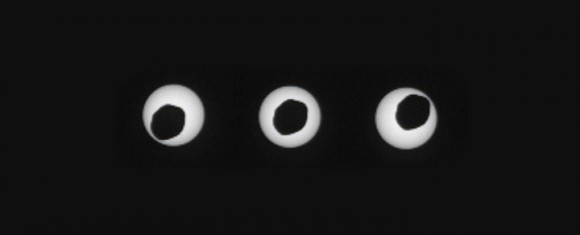

And don’t settle for a 99% partial eclipse just outside the path. “There’s no comparison between partial and total solar eclipses when it comes to sheer grandeur and beauty,” Michael Zeiler, longtime eclipse chaser and creator of the Great American Eclipse website told Universe Today. We witnessed the 1994 annular solar eclipse of the Sun from the shores of Lake Erie, and can attest that a 99% partial eclipse is still pretty darned bright!

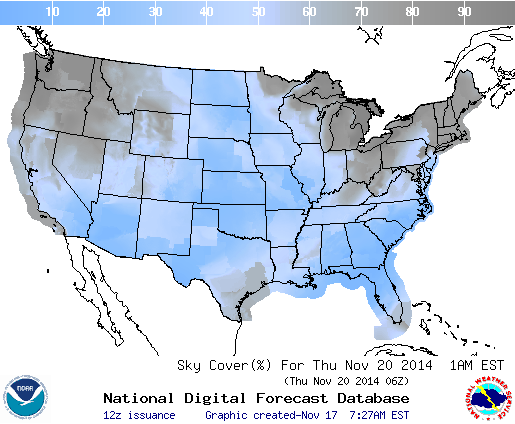

There are two total solar eclipses remaining worldwide up until 2017: One on March 20th, 2015 crossing the high Arctic, and another on March 9th 2016 over Southeast Asia. The 2017 eclipse offers a maximum of 2 minutes and 41 seconds of totality, and weather prospects for the eclipse in late August favors viewers along the northwestern portion of the track.

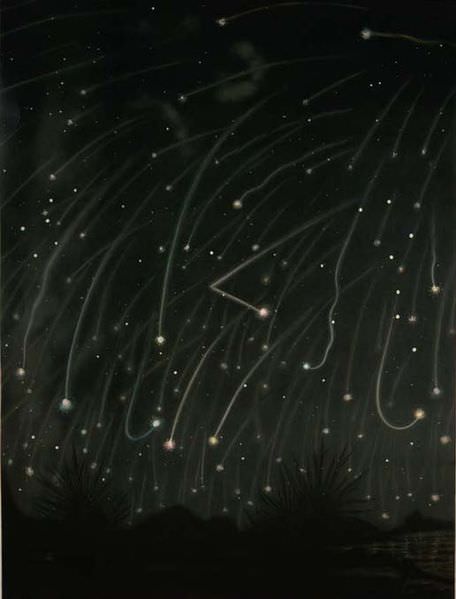

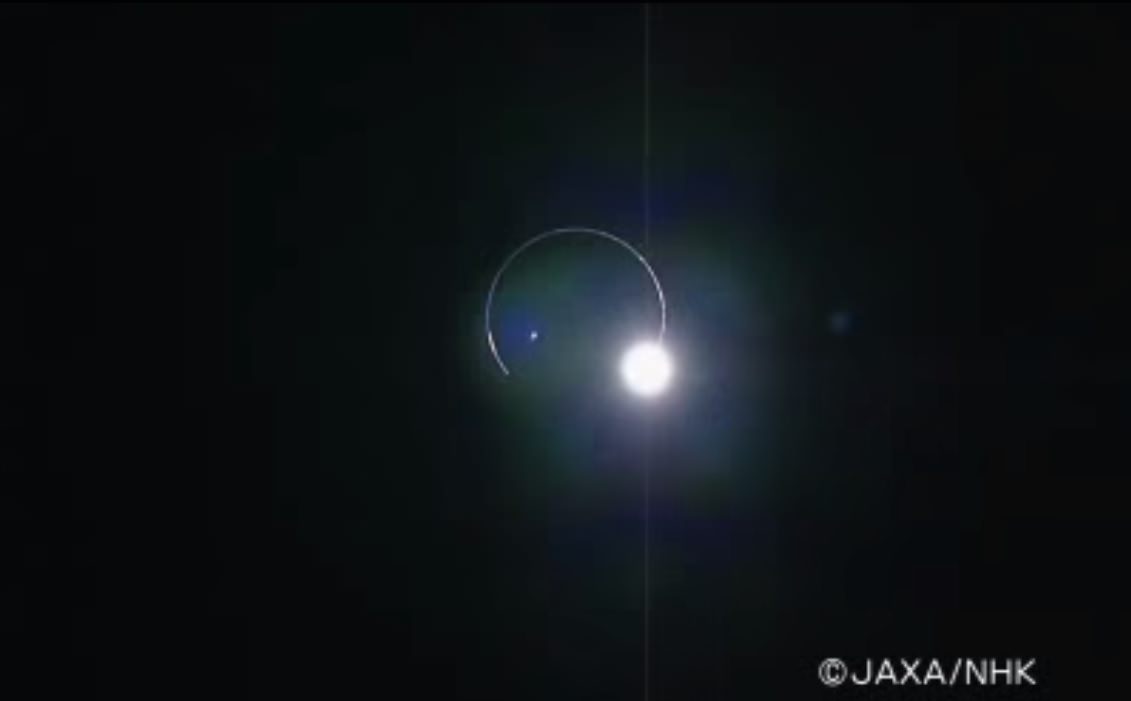

And though an armada of cameras will be prepared to capture the eclipse along its trek across the U.S., many veteran eclipse chasers suggest that first time viewers merely sit back and take in the moment. The onset of totality sees a bizarre sort of twilight fall across the landscape, as shadow bands skip across the countryside, temperatures drop, and wildlife is fooled into thinking that nightfall has come early.

And then, all too soon, the second set of blinding diamond rings burst through the lunar valleys, the eclipse glasses go back on, and totality is over. Which always raises the question heard throughout the crowd post-eclipse:

When’s the next one?

Well, the good news is, the United States will host a second total solar eclipse on April 8th, 2024, just seven years later! This path will run from the U.S. Southwest to New England, and crisscross the 2017 path right around Carbondale, Illinois.

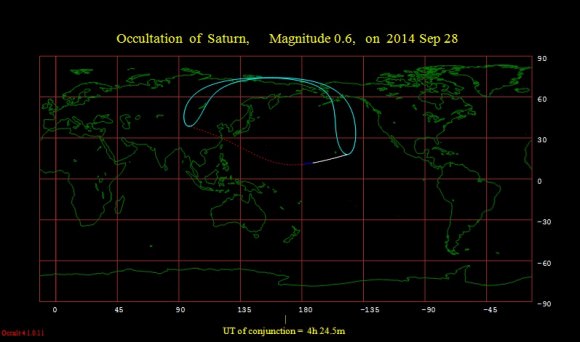

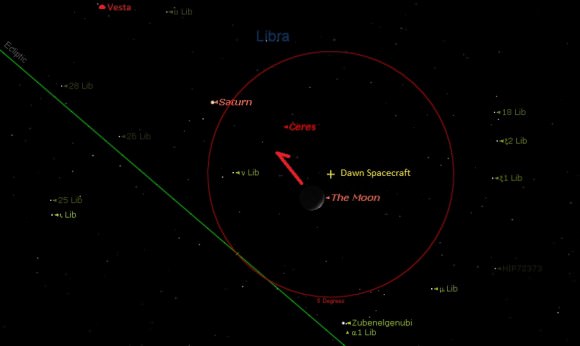

Will the woo that surfaced around the approach of Comet ISON and the lunar tetrad of “blood Moon eclipses” rear its head in 2017? Ah, eclipses and comets seem to bring ‘em out of the woodwork, and 2017 will likely see a spike in the talking-head gloom and doom videos ala YouTube. Some will no doubt cite the “perfection” seen during total solar eclipses as proof of divine inspiration, though this is actually just a product of our vantage point in time and space. In fact, annular eclipses are slightly more common than total solars in our current epoch, and will become more so as the Moon slowly recedes from the Earth. And we recently noted in our post on the mutual phenomena of Jupiter’s moons that solar eclipses very similar to those seen from the Earth can also be spied from Callisto.

Heads up to any future interplanetary eclipse resort developer: Callisto is prime real estate.

The 2017 total solar eclipse across America will be one for the history books, that’s for sure.

So get those eclipse safety glasses now, and be sure to keep ‘em handy through 2017 and onward to 2024!

-Read Dave Dickinson’s eclipse-fueled science fiction tales Shadowfall and Exeligmos.