Did you see it? Last night, the Red Planet rose in the east as it passed opposition for 2014, and astrophotographers the world over were ready to greet it. And although Mars gets slightly closer to us over the coming week, opposition marks the point at which Mars is 180 degrees “opposite” to the setting Sun in Right Ascension as viewed from our Earthly vantage point and denotes the center of the Mars observing season. Opposition only comes around once about every 26 months, so it’s definitely worth your while to check out Mars through a telescope now if you can. We’ve written about prospects for observing Mars this season, and the folks at Slooh and the Virtual Telescope Project also featured live views of the Red Planet last night. We also thought we’d include a reader roundup of pics from worldwide:

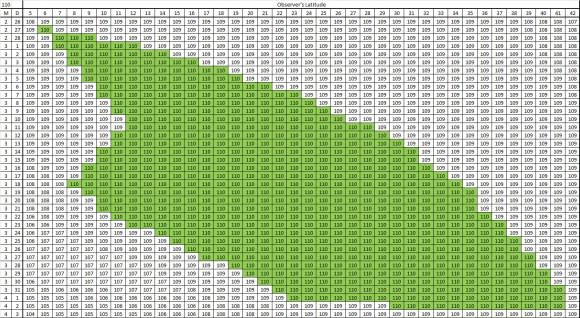

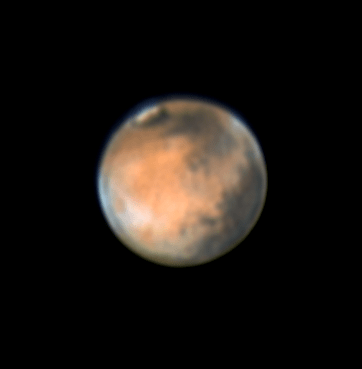

Even near opposition, Mars presents a challenge to observers. In 2014, Mars only reaches 15 arc seconds maximum in apparent size, a far cry from its 25″ appearance during the historic 2003 opposition. Now for the good news: we’re in a cycle of improving oppositions… the next one on May 22nd, 2016 will be better still, and the 2018 opposition will be nearly as favorable as the 2003 appearance!

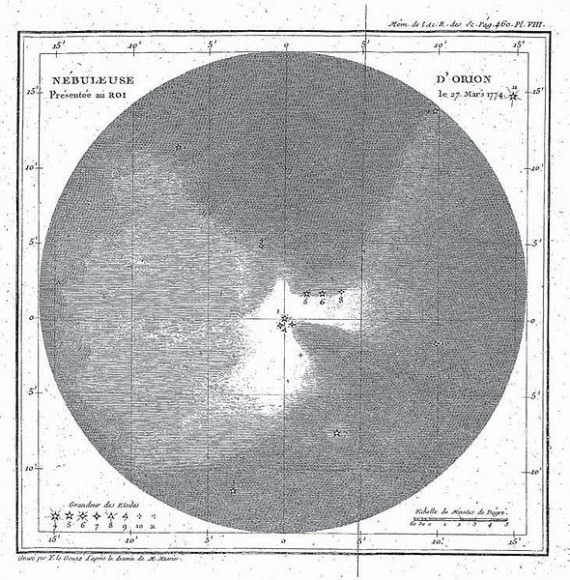

And you can see just how technology in the amateur astronomy community has improved with each successive appearance of Mars over the years. Early observers were restricted to sketching features glimpsed during fleeting moments of steady seeing. Even during the film era of photography, absurdly long focal lengths were required to yield even a tiny speck of a dot. And even then, the “graininess” of the film tended to smear and yield a blurry image with few details to be seen.

The advent of digital photography opened new vistas on planetary imaging. Now backyard astrophotographers are routinely taking images using stacking techniques and processing to “grab” and align those moments of good seeing. These images are often now better that what you’d see in a text book taken from professional observatories only a few decades ago!

And you can now easily modify a webcam to take decent planetary images that can then be stacked and processed with software freely available on the web.

…And check out this video animation also by Christian Fröschlin that shows the rotation (!) of Mars:

Shahrin Ahmad made an excellent video from Malaysia that demonstrates just what raw captured images of Mars look like before processing:

Note that the large dark triangular region is Syrtis Major.

The northern polar cap is currently tipped towards us, as it’s northern hemisphere summertime on Mars. Many images reflect this prominent feature, as well as the orographic clouds skirting the Hellas basin that have been the hallmark of the Mars opposition of 2014. These are also apparent visually at the eyepiece. It’s worth staying up a bit towards local midnight to observe and image Mars, as it transits at its maximum elevation — and is above the murk of the sky low to the horizon — right around this time.

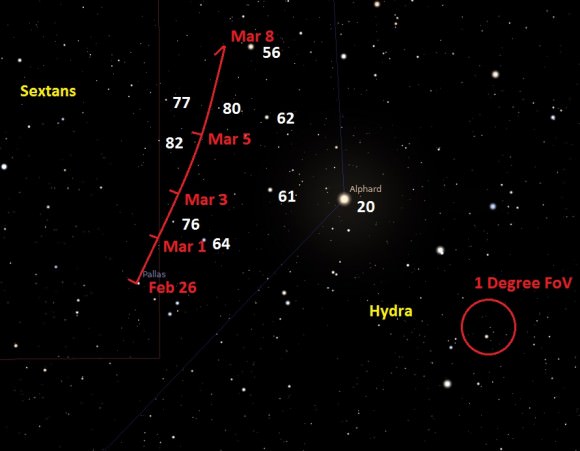

And Mars observing season doesn’t end this week. Mars makes its closest passage to the Earth for 2014 next Monday on April 14th at 0.618 Astronomical Units (A.U.s) distant. Mars will occupy the evening sky for the remainder of 2014 before finally reaching solar conjunction on June 14th, 2015. Mars will still be greater than a respectable 10″ in apparent size until June 24th and will continue to offer observers a fine view at the eyepiece.

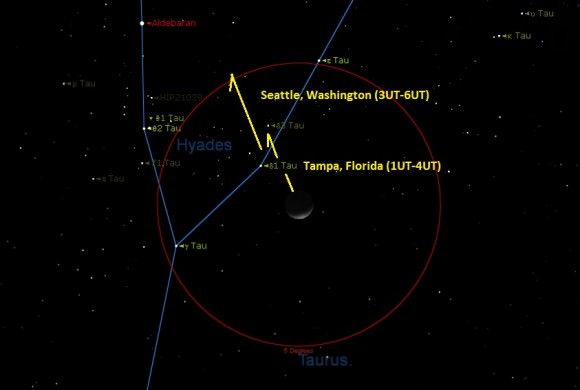

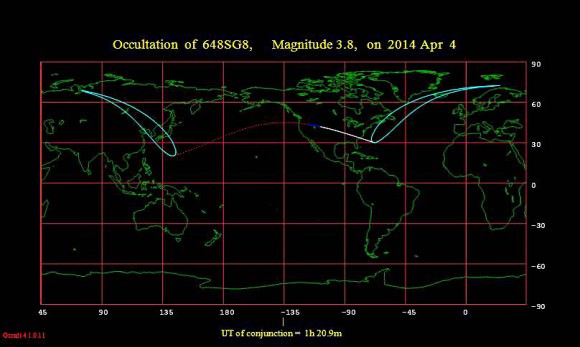

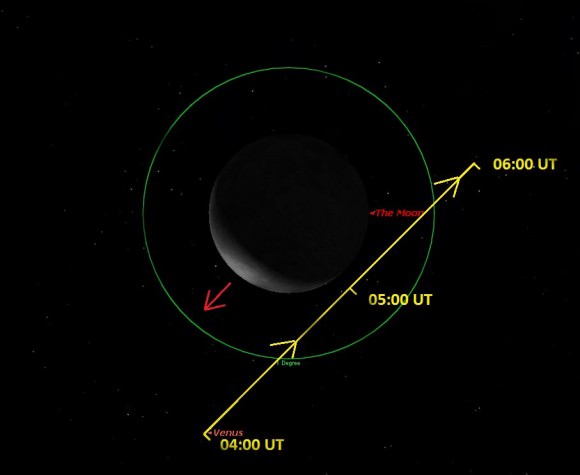

And don’t forget, that waxing gibbous Moon is now homing in on Mars and will only sit a few degrees away from the Red Planet and Spica on the night of the April 14th/15th, 2014 during a fine total lunar eclipse. And no, a “red” planet + a “blood red” eclipsed Moon does not equal doomsday… but it’ll make a great photo op!

… and finally, Mars and the bright blue-white star Spica offered us a fine morning view as the storm front passed over Astroguyz HQ here in Florida this AM:

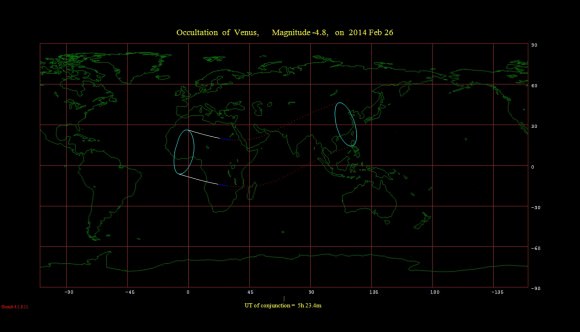

Want something more? Have you ever seen Mars… in the daytime? Currently shining at magnitude -1.5, its just possible if you known exactly where to look for it low to the east about 10 minutes or so before local sunset. In fact, near opposition is the only time you can carry this unusual feat of visual athletics out. The best chance in 2014 is on the evening of April 13th and 14th, when the waxing gibbous Moon lies nearby:

Good luck, and thanks to everyone who imaged Mars this season!