The issue of “what to wear?” takes on an extra dimension of life and death when it comes to space travel. Upon exiting a spacecraft on a spacewalk, an astronaut becomes his very own personal satellite in orbit about the Earth and must rely on the flimsy layer of his suit to provide them with a small degree of protection from radiation and extreme fluctuations of heat and cold.

We recently had a chance to see the past, present and future of space suit technology in the Smithsonian Institutions’ touring Suited for Space exhibit currently on display at the Tampa Bay History Center in Tampa, Florida.

Tampa Bay History Center Director of Marketing Manny Leto recently gave Universe Today an exclusive look at the traveling display. If you think you know space suits, Suited for Space will show you otherwise, as well as give you a unique perspective on a familiar but often overlooked and essential piece of space hardware. And heck, it’s just plain fascinating to see the design and development of some of these earlier suits as well as videos and stills of astronauts at work – and yes, sometimes even at play – in them.

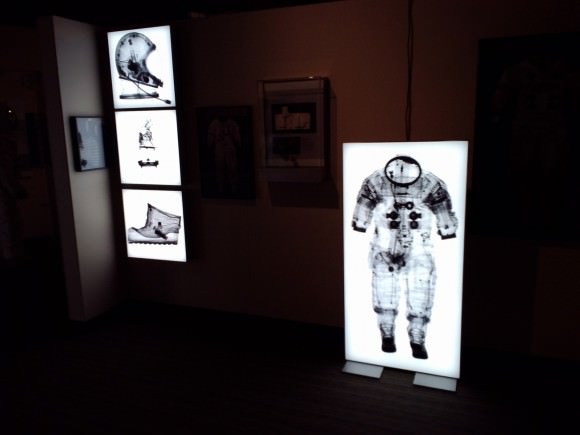

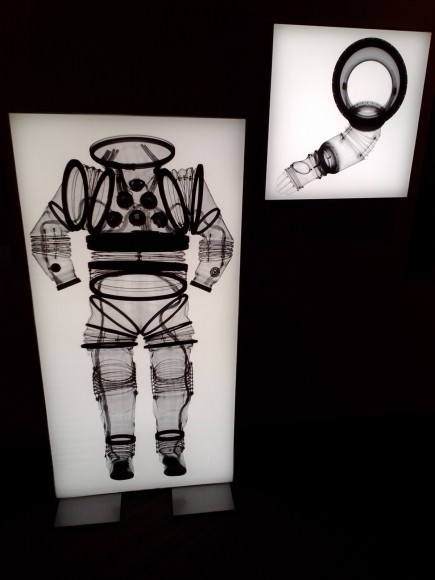

One of the highlights of the exhibit are some unique x-ray images of iconic suits from space travel history. Familiar suits become new again in these images by Smithsonian photographer Mark Avino, which includes a penetrating view of Neil Armstrong’s space suit that he wore on Apollo 11.

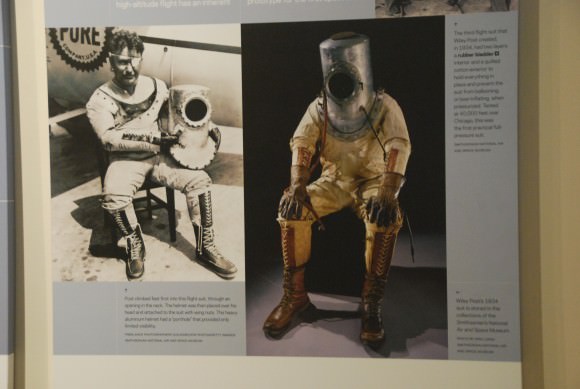

Space suits evolved from pressure suits developed for high-altitude flights in the 1950’s, and Suited for Space traces that progression. It was particularly interesting to see the depiction of Wiley Post’s 1934 suit, complete with steel cylindrical helmet and glass portal! Such early suits resembled diving bell suits of yore — think Captain Nemo in a chemsuit. Still, this antiquated contraption was the first practical full pressure suit that functioned successfully at over 13,000 metres altitude.

No suit that has been into space is allowed to tour due to the fragility of many historic originals that are now kept at the Smithsonian, though several authentic suits used in training during the U.S. space program are on display. We thought it was interesting to note how the evolution of the spacesuit closely followed the development of composites and materials through the mid-20th century. You can see the progression from canvas, glass and steel in the early suits right up though the advent of the age of plastic and modern fabrics. Designs have flirted with the idea of rigid and semi-rigid suits before settling on the modern day familiar white astronaut suit.

Spacesuit technology has also always faced the ultimate challenge of protecting an astronaut from the rigors of space during Extra-Vehicular Activity, or EVA.

Cosmonaut Alexey Leonov performed the first 12 minute space walk during Voskhod 2 back in 1965, and NASA astronaut Ed White became the first American to walk in space on Gemini 4 just months later. Both space walkers had issues with over-heating, and White nearly didn’t make it back into his Gemini capsule.

Designing a proper spacesuit was a major challenge that had to be overcome. In 1962, Playtex (yes THAT Playtex) was awarded a contract to develop the suits that astronauts would wear on the Moon. Said suits had 13 distinct layers and weighed 35 kilograms here on Earth. The Playtex industrial division eventually became known as the International Latex Corporation or ILC Dover, which still makes spacesuits for ISS crewmembers today. It’s also fascinating to see some of the alternate suits proposed, including one “bubble suit” with arms and legs (!) that was actually tested but, thankfully, was never used.

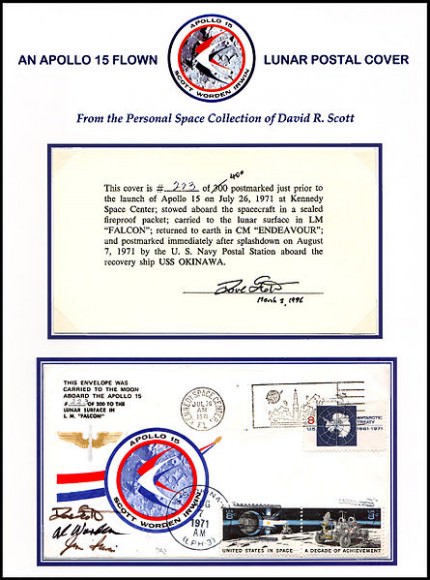

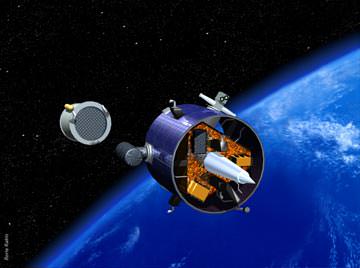

These suits were used by astronauts on the Moon, to repair Hubble, build the International Space Station and much more. Al Worden recounts performing the “most distant EVA ever” on the return from the Moon in his book Falling to Earth. This record will still stand until the proposed asteroid retrieval mission in the coming decade, which will see astronauts performing the first EVA ever in orbit around Earth’s Moon.

And working in a modern spacesuit during an EVA is anything but routine. CSA Astronaut Chris Hadfield said in his recent book An Astronaut’s Guide to Life on Earth that “Spacewalking is like rock climbing, weightlifting, repairing a small engine and performing an intricate pas de deux – simultaneously, while encased in a bulky suit that’s scraping your knuckle, fingertips and collarbone raw.”

And one only has to look at the recent drama that cut ESA astronaut Luca Parmitamo’s EVA short last year to realize that your spacesuit is the only thin barrier that exists between yourself and the perils of space.

“We’re delighted to host our first Smithsonian Institution Travelling Exhibition Service (SITES) and we think that Florida’s close ties to NASA and the space program make it a great fit for us,” said Rodney Kite-Powell, the Tampa Bay History Center’s Saunders Foundation Curator of History.

Be sure to catch this fascinating exhibit coming to a city near you!

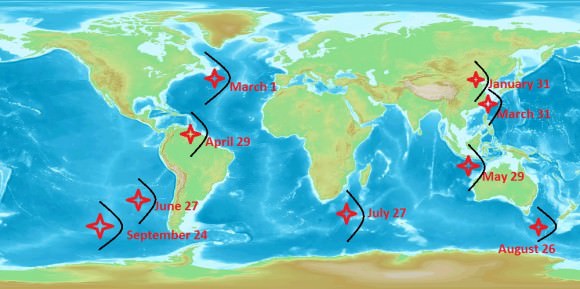

-And you can see these suits in action on the up and coming future EVAs for 2014.

-Here’s the schedule for Suited for Space Exhibit tour.

-Astronaut Nicole Stott (veteran of STS-128, -129, -133, & ISS Expeditions 20 and 21) will also be on hand at the Tampa Bay History Center on March 2014 (Date to be Announced) to present Suited for Space: An Astronaut’s View.

– Follow the Tampa Bay History Museum of Twitter as @TampaBayHistory.