Greetings, fellow SkyWatchers! With a whole lot less Moon present in the early evenings, it’s time to do some very different studies – from North to South! We’ll be having a look at planetary nebulae, globular clusters, galactic star clusters and some great galaxies, too! Need more? Then SH viewers can kick back and relax to a meteor shower, too! Whenever you’re ready, just meet me in the back yard…

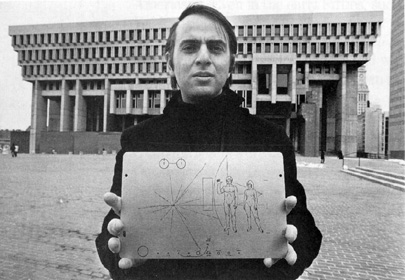

Monday, December 3 – Today in 1971, the Soviet Mars 3 became the first spacecraft to make a soft landing on the red planet, and two years later on this same date the Pioneer 10 mission became the first spacecraft to fly by Jupiter. One year later on this same date? Pioneer 11 did the same thing!

Tonight let’s familiarize ourselves with the vague constellation of Fornax. Its three brightest stars form a shallow V just south of the Cetus/Eridanus border and span less than a handwidth of sky. Although it’s on the low side for northern observers, there is a wealth of sky objects in this area.

Try having a look at the easternmost star – 40-light-year distant Alpha. At magnitude 4, it is not easy, but what you’ll find there is quite beautiful. For binoculars, you’ll see a delightful cluster of stars around this long-term binary – but telescopes will enjoy it as a great golden double star! First measured by John Herschel in 1835, the distance between the pair has narrowed and widened over the last 172 years and it is suspected its orbital period may be 314 years. While the 7th magnitude secondary can be spotted with a small scope – watch out – because it may also be a variable which drops by as much as a full magnitude!

Tuesday, December 4 – Today in 1978, the Pioneer/Venus Orbiter became the first spacecraft to orbit Venus. And in 1996, the Mars Pathfinder mission was launched!

For larger telescopes, set sail for Beta Fornacis tonight and head 3 degrees southwest (RA 02 39 42.5 Dec -34 16 08.0) for a real curiosity – NGC 1049.

At magnitude 13, this globular cluster is a challenge for even large scopes – and with good reason. It isn’t in our galaxy. This globular cluster is a member of the Fornax Dwarf Galaxy – a one degree span that’s so large it was difficult to recognize as extra-galactic – or at least it was until the great Harlow Shapely figured it out! NGC 1049 was first discovered and cataloged by John Herschel in 1847, only to be reclassified as “Hodge 3″ in a 1961 study of the system’s five globular clusters by Paul Hodge. Since that time, yet another globular has been discovered! Good luck…

Wednesday, December 5 – How about something a little more suited to the mid-sized scope tonight? Set your sights on Alpha Fornacis and let’s head about 3 fingerwidths northeast (RA 03 33 14.65 Dec -25 52 18.0) for NGC 1360.

In a 6? telescope, you’ll find the 11th magnitude central spectroscopic double star of this planetary nebula to be very easy – but be sure to avert because the nebula itself is very elongated. Like most of my favorite things, this planetary is a rule-breaker since it doesn’t have an obvious shell structure. But why? Rather than believe it is not a true planetary by nature, studies have shown that it could quite possibly be a very highly evolved one – an evolution which has allowed its gases to begin to mix with the interstellar medium. Although faint and diffuse for northern observers, those in the south will recognize this as Bennett 15!

Tonight let’s take advantage of early dark and venture further into Cassiopeia. Returning to Gamma, we will move towards the southeast and identify Delta. Also known as Ruchbah, this long-term and very slight variable star is about 45 light-years away, but we are going to use it as our marker as we head just one degree northeast and discover M103. As the last object in the original Messier catalog, M103 (NGC 581) was actually credited to Mechain in 1781. Easily spotted in binoculars and small scopes, this rich open cluster is around magnitude 7, making it a prime study object. At about 8000 light-years away and spanning approximately 15 light-years, M103 offers up superb views in a variety of magnitudes and colors, with a notable red in the south and a pleasing yellow and blue double to the northwest.

Viewers with telescopes and larger binoculars are encouraged to move about a degree and half east of M103 to view a small and challenging chain of open clusters, NGCs 654 (Right Ascension: 1 : 44.1 – Declination: +61 : 53), 663 and 659! Surprisingly larger than M103, NGC 663 (Right Ascension: 1:46.0 – Declination: +61:15) is a lovely fan-shaped concentration of stars with about 15 or so members that resolve easily to smaller aperture. For the telescope, head north for NGC 654, (difficult, but not impossible to even a 114mm scope) which has a bright star on its southern border. South of NGC 663 is NGC 659 (Right Ascension: 1 : 44.2 – Declination: +60 : 42) which is definitely a challenge for small scopes, but its presence will be revealed just northeast of two conspicuous stars in the field of view.

Thursday, December 6 – For northern observers clamoring for brighter stellar action, look no further tonight than the incredible “Double Cluster” about four fingerwidths southeast of Delta Cassiopeiae (Right Ascension: 2 : 22.4 – Declination: +57 : 07). At a dark sky site, this incredible pair is easily located visually and stunning in any size binoculars and telescopes. As part of the constellation of Perseus, this double delight is around 7000 light-years away and less than 100 light-years separates the pair. While open clusters in this area are not really a rarity, what makes the “Double Cluster” so inviting is the large amount of bright stars within each of them. Well known since the very beginnings of astronomy, take the time to have a close look at both Chi (NGC 884) and H Persei very carefully. Note how many colorful stars you see, and the vast array of double, multiple and variable systems!

Now, let’s return again to Cassiopeia and start at the central-most bright star, Gamma. Four degrees southeast is our marker for this starhop, Phi Cassiopeiae. By aiming binoculars or telescopes at this star, it is very easy to locate an interesting open cluster, NGC 457 (Right Ascension: 1 : 19.1 – Declination: +58:20), because they will be in the same field of view.

This bright and splendid galactic cluster has received a variety of names over the years because of its uncanny resemblance to a figure. Some call it an “Angel,” others see it as the “Zuni Thunderbird;” I’ve heard it called the “Owl” and the “Dragonfly,” but perhaps my favorite is the “E.T. Cluster,” As you view it, you can see why! Bright Phi and HD 7902 appear like “eyes” in the dark and the dozens of stars that make up the “body” appear like outstretched “arms” or “wings.” (For E.T. fans? Check out the red “heart” in the center.)

All this is very fanciful, but what is NGC 457, really? Both Phi and HD 7902 may not be true members of the cluster. If 5th magnitude Phi were actually part of this grouping, it would have to have a distance of approximately 9300 light-years, making it the most luminous star in the sky, far outshining even Rigel! To get a rough idea of what that means, if we were to view our own Sun from this far away, it would be no more than magnitude 17.5. The fainter members of NGC 457 comprise a relatively young star cluster that spans about 30 light-years. Most of the stars are only about 10 million years old, yet there is an 8.6 magnitude red supergiant in the center. No matter what you call it, NGC 457 is an entertaining and bright cluster that you will find yourself returning to again and again. Enjoy!

Friday, December 7 – Today is the birthday of Gerard Kuiper. Born 1905, Kuiper was a Dutch-born American planetary scientist who discovered moons of both Uranus and Neptune. He was the first to know that Titan had an atmosphere, and he studied the origins of comets and the solar system.

Tonight let’s honor his achievements as we have a look at another bright open cluster known by many names: Herschel VII.32, Melotte 12, Collinder 23, and NGC 752. You’ll find it three fingerwidths south (RA 01 57.8 Dec +37 41) of Gamma Andromedae…

Under dark skies, this 5.7 magnitude cluster can just be spotted with the unaided eye, is revealed in the smallest of binoculars, and can be completely resolved with a telescope. Chances are it was first discovered by Hodierna over 350 years ago, but it was not cataloged until Sir William gave it a designation in 1786. But give credit where credit is due… For it was Caroline Herschel who observed it on September 28, 1783! Containing literally scores of stars, galactic cluster NGC 752 could be well over a billion years old, strung out in chains and knots in an X pattern of a rich field. Take a close look at the southern edge for orange star 56: while it is a true binary star, the companion you see is merely optical. Enjoy this unsung symphony of stars tonight!

Now, let’s go back to Cassiopeia. Remembering Alpha’s position as the westernmost star, go there with your finderscope or binoculars and locate bright Sigma and Rho (each has a dimmer companion). They will appear to the southwest of Alpha. It is between these two stars that you will find NGC 7789 (RA 23 57 24.00 Dec +56 42 30.0).

Absolutely one of the finest of rich galactic opens bordering on a loose globular, NGC 7789 has a population of about 1000 stars and spans a mind-boggling 40 light-years. At well over a billion years old, the stars in this 5000 light-year distant galactic cluster have already evolved into red-giants or super-giants. Discovered by Caroline Herschel in the 18th century, this huge cloud of stars has an average magnitude of 10, making it a great large binocular object, a superb small telescope target, and a total fantasy of resolution for larger instruments.

Saturday, December 8 – Today in history (1908) marks “first light” for the 60? Hale Telescope at Mt. Wilson Observatory. Not only was it the largest telescope of the time, but it ended up being one of the most productive of all. Almost 100 years later, the 60? Hale is still in service as a public outreach instrument. If we could use the 60? tonight to study, where would we go? My choice would be the Fornax Galaxy Cluster!

Containing around 20 galaxies brighter than 13th magnitude in a one degree field, here is where a galaxy hunter’s paradise begins! About a degree and a half north of Tau Fornacis is the large, bright and round spiral NGC 1398 (Right Ascension: 3 : 38.9 – Declination: -26 : 20). A little more than a degree west-northwest is the easy ring of the planetary nebula NGC 1360. Look for the concentrated core and dark dustlane of NGC 1371 a degree north-northeast – or the round NGC 1385 which accompanies it. Why not visit Bennett 10 or Caldwell 67 as we take a look at NGC 1097 (Right Ascension: 2:46.3 – Declination: -30:17) about 6 degrees west-southwest of Alpha? This one is bright enough to be caught with binoculars!

Telescopes will love NGC 1365 (Right Ascension: 3:33.6 – Declination: -36:08) at the heart of the cluster proper. This great barred spiral gives an awesome view in even the smallest of scopes. As you slide north, you will encounter a host of galaxies, NGCs 1386, 1389, 1404, 1387, 1399, 1379, 1374, 1381 and 1380. There are galaxies everywhere! But, if you lose track? Remember the brightest of these are two ellipticals – 1399 and 1404. Have fun!

Now, let’s haunt Cassiopeia one last time – with studies for the seasoned observer. Our first challenge of the evening will be to return to Gamma where we will locate two patches of nebulosity in the same field of view. IC 59 and IC 63 are challenging because of the bright influence of the star, but by moving the star to the edge of the field of view you may be able to locate these two splendid small nebulae. If you do not have success with this pair, why not move on to Alpha? About one and a half degrees due east, you will find a small collection of finderscope stars that mark the area of NGC 281 (RA 00 52 25.10 Dec +56 33 54.0). This distinctive cloud of stars and ghostly nebulae make this NGC object a fine challenge!

The last things we will study are two small elliptical galaxies that are achievable in mid-sized scopes. Locate Omicron Cassiopeiae about 7 degrees north of M31 and relocate our earlier study, a galactic pair that is associated with the Andromeda group – NGC 185 (RA 00 38 57.40 Dec +48 20 14.4) and NGC 147 (RA 00 33 11.79 Dec +48 30 24.8). The constellation of Cassiopeia contains many, many more fine star clusters, and nebulae – and even more galaxies. For the casual observer, simply tracing over the rich star fields with binoculars is a true pleasure, for there are many bright asterisms best enjoyed at low power. Scopists will return to “rock with the Queen” year after year for its many challenging treasures. Enjoy it tonight!

Sunday, December 9 – Southern Hemisphere viewers, you’re in luck! This is the maximum of the Puppid-Velid meteor shower. With an average fall rate of about 10 per hour, this particular meteor shower could also be visible to those far enough south to see the constellation of Puppis. Very little is known about this shower except that the streams and radiants are very tightly bound together. Since studies of the Puppid-Velids are just beginning, why not take the opportunity to watch? Viewing will be possible all night long and although most of the meteors are faint, this one is known to produce an occasional fireball.

Since we’re favoring the south tonight, let’s set northern observers toward a galaxy cluster – Abell 347 – located almost directly between Gamma Andromedae and M34. Here you will find a grouping of at least a dozen galaxies that can be fitted into a wide field view. Let’s tour a few…

The brightest and largest is NGC 910 (Right Ascension: 2 : 25.4 – Declination: +41:50), a round elliptical with a concentrated nucleus. To the northwest you can catch faint, edge-on NGC 898. NGC 912 is northeast of NGC 910, and you’ll find it quite faint and very small. NGC 911 to the north is slightly brighter, rounder, and has a substantial core region. NGC 909 further north is fainter, yet similar in appearance. Fainter yet is more northern NGC 906, which shows as nothing more than a round contrast change. Northeast is NGC 914, which appears almost as a stellar point with a very small haze around it. To the southeast is NGC 923 which is just barely visible with wide aversion as a round contrast change. Enjoy this Abell quest!

And the countdown is on… Enjoy these last few weeks of the SkyWatcher, cuz’ the old woman is going to retire at the end of this year! Until then? Clear skies!