Turns out, our seemly placid star had a criminal youth of cosmic proportions.

A recent study out from Leiden Observatory and Cornell University may shed light on the curious case of one of the solar system’s more exotic objects: 90377 Sedna.

A team led by astronomer Mike Brown discovered 90377 Sedna in late 2003. Provisionally named 2003 VB12, the object later received the name Sedna from the International Astronomical Union, after the Inuit goddess of the sea.

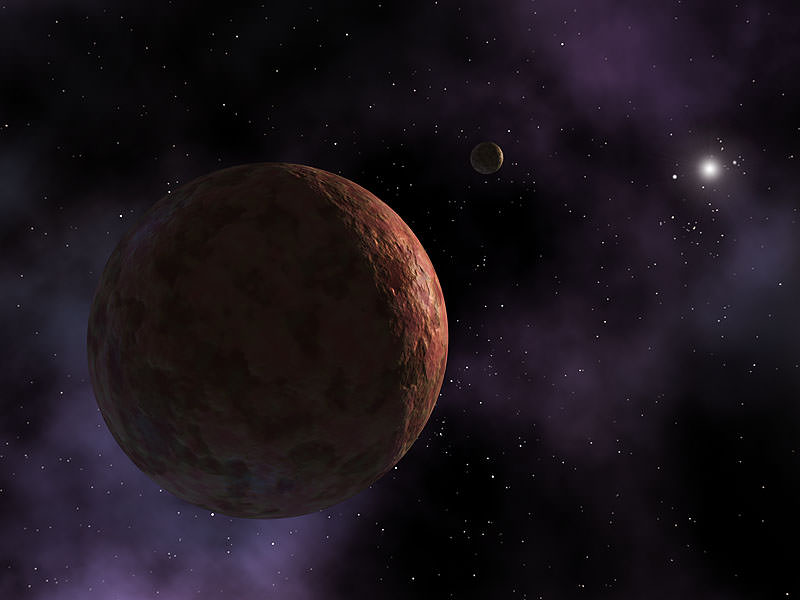

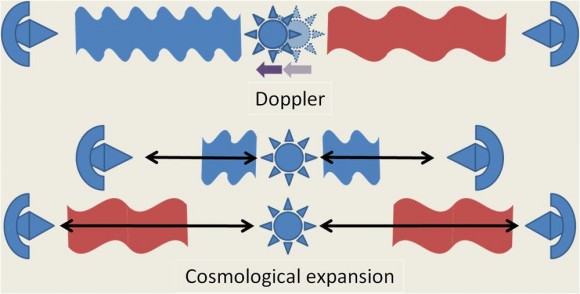

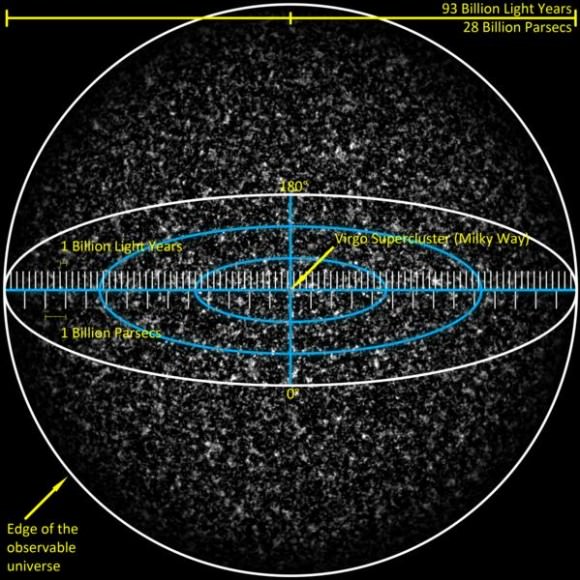

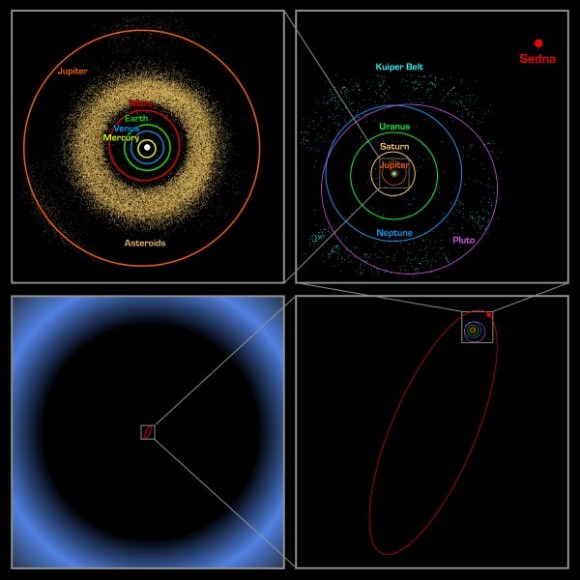

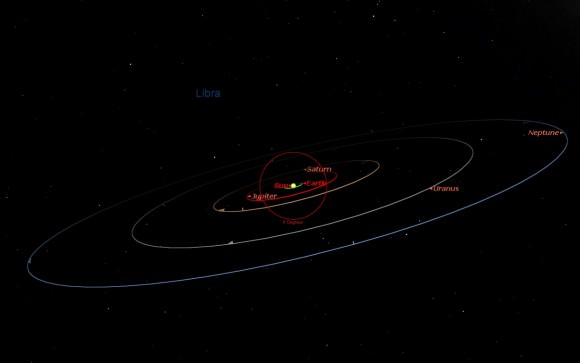

From the start, Sedna was an odd-ball. Its 11,400 year orbit takes it from a perihelion of 76 astronomical units (for context, Neptune is an average of 30 AUs from the Sun) to an amazing 936 AUs from the Sun. (A thousand AUs is 1.6% of a light year, and 0.4% of the way to Proxima Centauri, the closest star to our solar system). Currently at a distance of 86 AU and headed towards perihelion in 2076, we’re lucky we caught Sedna as it ‘neared’ (we use the term ‘near’ loosely in this case!) the Sun.

But this strange path makes you wonder what else is out there, and how Sedna wound up in such an eccentric orbit.

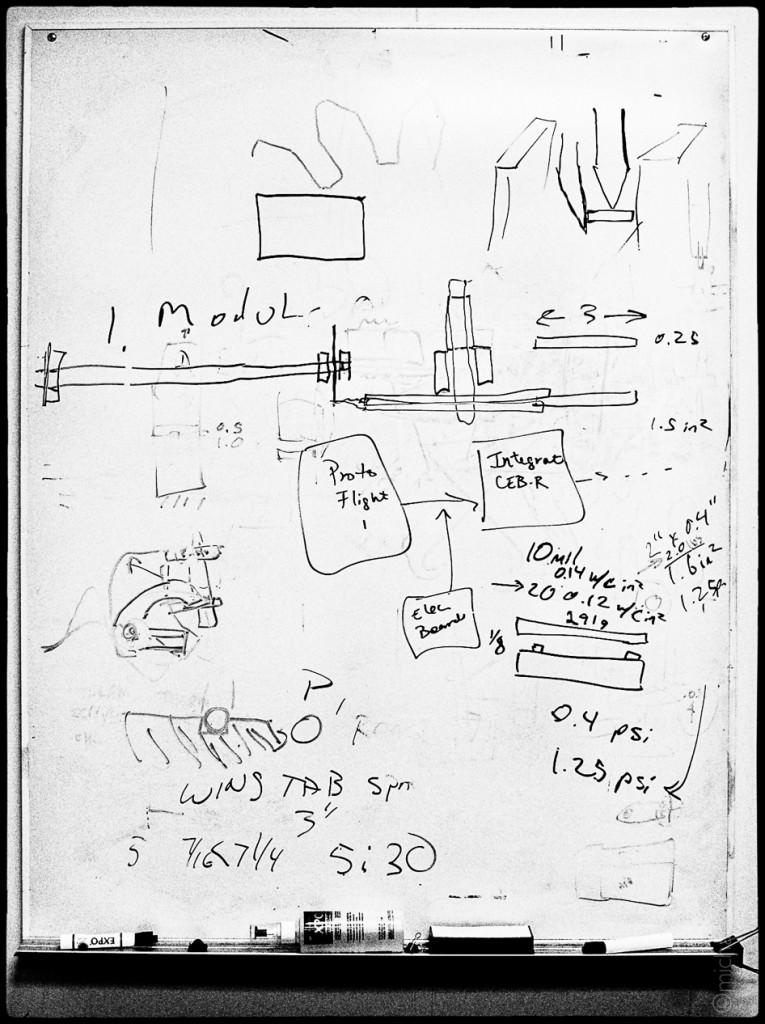

The study, entitled How Sedna and family were captured in a close encounter with a solar sibling looks at the possibility that Sedna may have been snatched from another star early on in our Sun’s career (of interstellar crime, perhaps?) The team used supercomputer simulations modeling 10,000 encounters to discover which types of near stellar passages might result in an ice dwarf world in a Sedna-like orbit.

“We constrained the parent star of Sedna to have between one and two times the mass of the Sun and its closest approach to be 200-400 AUs,” Dr. Lucie Jilkova of Leiden Observatory told Universe Today. “Such a close encounter probably happened while the Sun was still a member of its birth star cluster — a family of about 1,000 stars, so called solar siblings, born at the same time relatively close together — which was about 4 billion years ago.”

The best fit for what we see today in the outer solar system in the case of Sedna, is a close (340 AU) passage from the Sun — that’s over 11 times Neptune’s distance — of a 1.8 solar mass star inclined at an angle of 17-34 degrees to the ecliptic. Sedna’s current orbital inclination is 12 degrees.

Rise of the Sednitos

The paper assigns the term ‘Sednitos’ (also sometimes referred to as ‘Sednoids’) for these Edgeworth-Kuiper Belt intruders with similar characteristics to Sedna. In 2012, 2012 VP113, dubbed the ‘twin of Sedna,’ was discovered by astronomers at the Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory in a similar looping orbit. The ‘VP’ designation earned the as yet unnamed remote world the brief nickname ‘Biden’ after U.S. Vice President Joe Biden… hey, it was an election year.

There’s good reason to believe something(s?) out there shepherding these Senitos into a similar orbit with a comparable argument of perihelion. Researchers have suggested the existence of one or several planetary mass objects loitering out in the 200-250 AU range of the outer solar system… note that this is

a separate scientific-based discussion versus any would-be Nibiru related non-sense, don’t even get

us started…

If researchers in the study are correct, Sedna may have lots of company, with perhaps 930 planetesimals predicted in the ‘Sednito region’ of the solar system from 50 to 1,000 AUs and 430 more additional planetesimals littering the inner Oort cloud from the same early event.

“We focused on a particular example of a stellar encounter with characteristics from the ranges mentioned,” Dr. Jilkova said. “For this example, we estimated that there would be about 430 bodies similar to Sedna in the outer solar system (beyond 75 AU).”

Fun fact: One possible controversial candidate for the birth cluster of Sol and our solar system is the open cluster M67 in Cancer. It’s an intriguing notion to try and track down the star we stole Sedna from 4 billion years ago using spectral analysis, though researchers in the study point out that the other more massive star is probably an aging white dwarf by now.

Astronomy from the surface of Sedna is mind-bending to contemplate. Currently 86 AU from the Sun and headed towards perihelion in 2076, Sol would appear only 20” across from the surface of Sedna, but would still shine at magnitude -17 to -18 near perihelion, about 40 to 100 times brighter than a Full Moon. Fast forward about 5,500 years towards aphelion, however, and the Sun would dim to a paltry magnitude -12, a full magnitude (2.5 times) dimmer than the Full Moon.

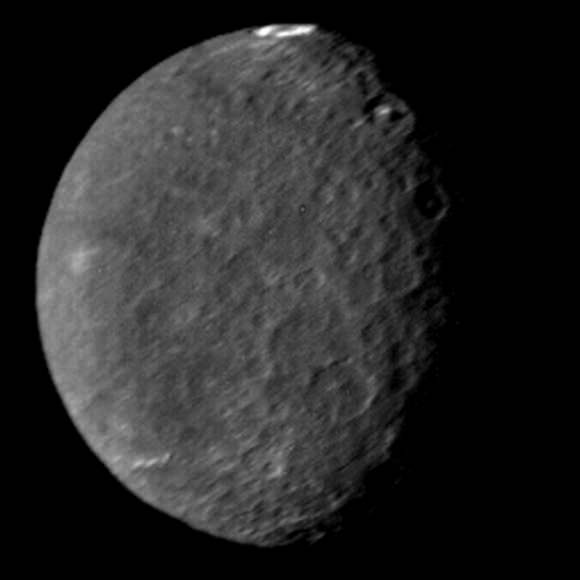

Shining at magnitude +21 in the constellation Taurus, astronomers know little else about Sedna. Based on brightness estimates, Sedna measures about 1,000 km in diameter. It does appear to be the reddest object in the solar system, and may turn out to be the ‘red twin of Pluto’ as recently revealed by NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft, complete with a surface rich in tholins.

And a new generation of observatories may uncover a treasure trove of Sednitos. The European Space Agency’s Gaia astrometry mission should uncover lots of new asteroids, comets, exoplanets and distant Kuiper Belt objects as a spin-off to its primary mission. Then there’s the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope, set to see first light in 2019.

“The key piece of the puzzle is to actually observe more Sedna-like objects.” Dr Jilkova said. “Currently, we know only of two such bodies. More discoveries are expected in the following years and they will shed light on the origin of Sedna and its family and the ‘criminal record’ of the Sun.”

It’s a fascinating story of interstellar whodunit for sure, as our Sun’s early days of wanton juvenile delinquency unravel before the eyes of modern day astronomical detectives.