Back in 2010, astronomers discovered an asteroid that was breaking apart due to a head-on collision with another asteroid. But now they have seen an asteroid break apart – with no recent collision required.

Asteroid P/2013 R3 appears to be crumbling apart in space, and astronomers using the Hubble Space Telescope recently saw the asteroid breaking into as many as 10 smaller pieces. The best explanation for the break-up is the Yarkovsky–O’Keefe–Radzievskii–Paddack (YORP) effect, a subtle effect from sunlight that can change the asteroid’s rotation rate and basically cause a rubbly-type asteroid to spin apart.

“This is a really bizarre thing to observe — we’ve never seen anything like it before,” said co-author Jessica Agarwal of the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research, Germany. “The break-up could have many different causes, but the Hubble observations are detailed enough that we can actually pinpoint the process responsible.”

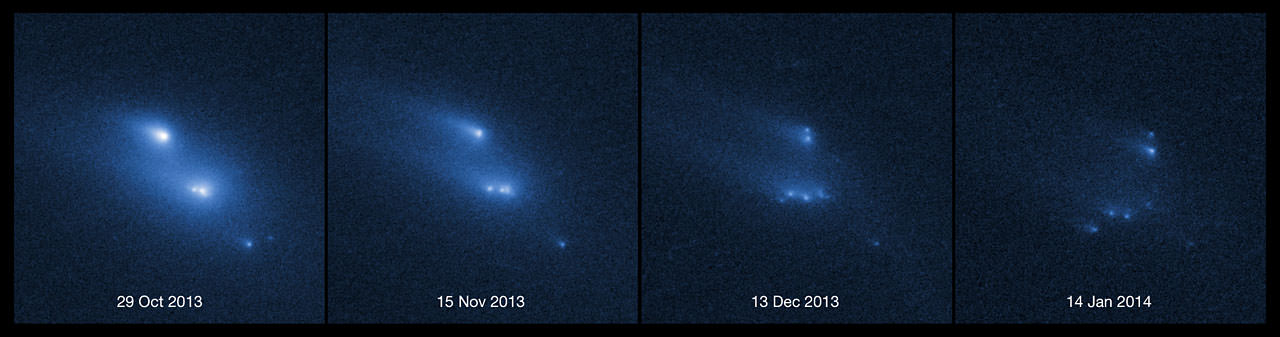

Astronomers first noticed this asteroid on September 15, 2013 and it appeared as a weird, fuzzy-looking object, as seen by the Catalina and Pan-STARRS sky-survey telescopes. A follow-up observation on Oct. 1 with the W.M. Keck telescope on Hawaii’s Mauna Kea revealed three co-moving bodies embedded in a dusty envelope that is nearly the diameter of Earth.

Then on October 29, 2013, astronomers used the Hubble Space Telescope to observe the object and saw there were actually 10 embedded objects, each with comet-like dust tails. The four largest rocky fragments are up to 200 meters/yards in radius, about twice the length of a football field.

The Hubble data showed that the fragments are drifting away from each other at a leisurely pace of 1.6 km/hr (one mile per hour), which would be slower than a strolling human.

“Seeing this rock fall apart before our eyes is pretty amazing,” said David Jewitt, from UCLA’s Department of Physics and Astronomy, who led the investigation.

The slowness of the speed at which the pieces are coming apart makes it unlikely that the asteroid is disintegrating because of a collision. That would be instantaneous and violent, with the pieces traveling away from each other at much higher speeds.

Loading player…

Jewitt also said the asteroid is not coming unglued due to the pressure of interior ices warming and vaporizing, like comets do as they approach the Sun. The asteroid is too cold for ices to significantly sublimate, and it has presumably maintained its nearly 480 million-km (300 million–mile) distance from the Sun for much of its life.

Jewitt described the YORP torque effect as like grapes on a stem being gently pulled apart due to centrifugal force of an unusually shaped asteroid as it speeds up in its spin. This effect occurs when light from the Sun is absorbed by a body and then re-emitted as heat. When the shape of the emitting body is not perfectly regular, more heat is emitted from some regions than others. This creates a small imbalance that causes a small but constant torque on the body, which changes its spin rate. This effect has been discussed by scientists for several years but, so far, never reliably observed.

For the break-up to happen, P/2013 R3 must have a weak, fractured interior, probably as the result of previous but ancient collisions with other asteroids. Most small asteroids, in fact, are thought to have been severely damaged in this way, giving them a “rubble pile” internal structure. P/2013 R3 itself is probably the product of collisional shattering of a bigger body some time in the last billion years.

With Hubble’s recent discovery of an a different active asteroid spouting six tails (P/2013 P5), astronomers are seeing more circumstantial evidence that the pressure of sunlight may be the primary force that disintegrates small asteroids (less than a mile across) in the Solar System.

The asteroid’s remnant debris, estimated at weighing in at 200,000 tons, in the future will provide a rich source of meteoroids, Jewitt said. Most will eventually plunge into the sun, but a small fraction of the debris may one day enter the Earth’s atmosphere to blaze across the sky as meteors, he said.

The discovery is published online March 6 in Astrophysical Journal Letters. A preprint of the paper can be found here.

Sources: UCLA, Hubble ESA