For the first time, astronomers have found conclusive evidence of water in the hazy atmospheres of planets orbiting other stars. Using the Hubble Space Telescope, two teams of scientists found faint but clear signatures of water in the atmospheres of five exoplanets. All five are so-called ‘hot Jupiters,’ massive worlds that orbit close to their host stars.

“To actually detect the atmosphere of an exoplanet is extraordinarily difficult. But we were able to pull out a very clear signal, and it is water,” said Drake Deming from the University of Maryland, who led a study characterizing the atmospheres of two of the five planets.

“We’re very confident that we see a water signature for multiple planets,” said Avi Mandell, a planetary scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, and lead author of another paper on the remaining three exoplanets. “This work really opens the door for comparing how much water is present in atmospheres on different kinds of exoplanets, for example hotter versus cooler ones.”

The five planets are all well-studied, and would not be friendly places for life as we know it — with blazing temperatures and unusual conditions. WASP-17b is an unusual planet in a retrograde orbit, and sodium had already been detected in its atmosphere.

HD209458b is much-studied windy world, with raging storms, and organic molecules and water had already been detected on this planet in previous studies.

The atmosphere of WASP-12b already has been found to hold vast amounts of carbon as well as water. WASP-19b orbits a nearby star, and has one of the shortest orbital periods of any known planetary body, about 0.7888399 days or approximately 18.932 hours. XO-1b has the distinction of being discovered by amateur astronomers

The astronomers involved in the new studies say the strengths of the water signatures in each world varied, with WASP-17b and HD209458b having the strongest signals.

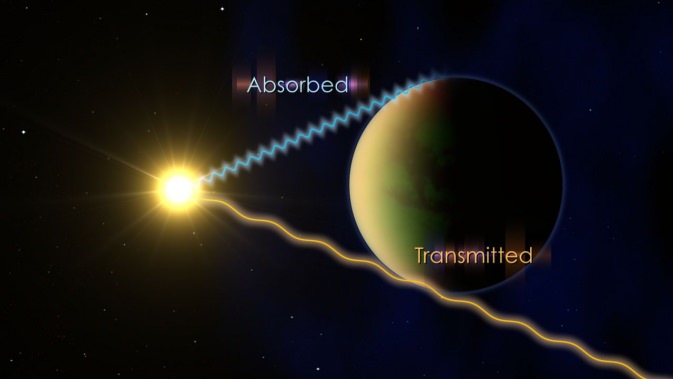

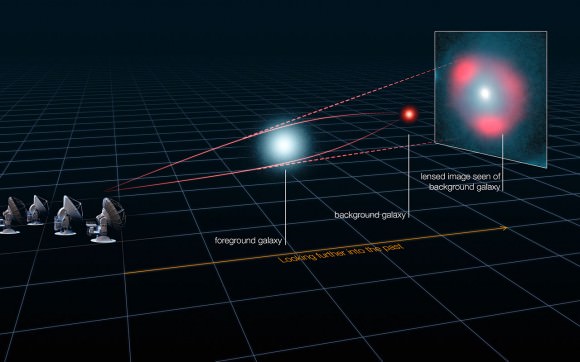

Currently, studying exoplanet atmospheres can be done when the planets are passing in front of their stars. Researchers can identify the gases in a planet’s atmosphere by determining which wavelengths of the star’s light are transmitted and which are partially absorbed. Deming’s team employed a new technique with longer exposure times, which increased the sensitivity of their measurements.

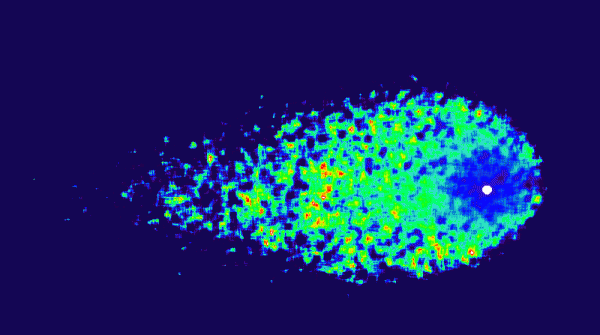

In both studies, scientists used Hubble’s Wide Field Camera 3 to explore the details of absorption of light through the planets’ atmospheres. The observations were made in a range of infrared wavelengths where a pattern that signifies the presence of water would appear if water were present. The teams compared the shapes and intensities of the absorption profiles, and the consistency of the signatures gave them confidence they saw water.

“These studies, combined with other Hubble observations, are showing us that there are a surprisingly large number of systems for which the signal of water is either attenuated or completely absent,” said Heather Knutson of the California Institute of Technology, a co-author on Deming’s paper. “This suggests that cloudy or hazy atmospheres may in fact be rather common for hot Jupiters.”

Read the teams paper: Deming et al, Mandell et al.

Sources: HubbleSite, University of Maryland.