Are you ready for a new galactic puzzle? Then let’s start with some clues. It has been long assumed that some galaxies reach a point in their evolution when star formation stops. In the distant past, these saturated galaxies appeared smaller than those formed more recently. This is what baffles astronomers. Why do some galaxies continue to grow if they are no longer forming stars? Thanks to some very astute Hubble Space Telescope observations, a team of astronomers has found what appears to be a rather simple explanation. Which came first? The chicken or the egg?

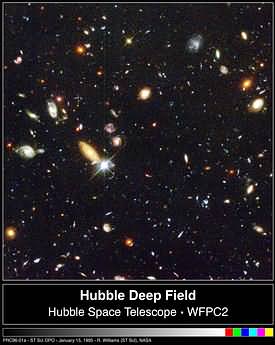

Until now, these diminutive, turned-off galaxies were theorized to continue to grow into the more massive, saturated galaxies observed closer to us. Because they no longer have active star-forming regions, it was assumed they gained their extra mass by combining with other smaller galaxies – ones five to ten times less in overall size. However, for this theory to be plausible, it would take a host of small galaxies to be present for the saturated population to consume… and it’s just not happening. Because we simply did not have the data available about such a large number of galaxies, it was impossible to count and identify potential candidates, but the Hubble COSMOS survey has provided an eight billion year look at the cosmic history of turned-off galaxies.

“The apparent puffing up of quenched galaxies has been one of the biggest puzzles about galaxy evolution for many years,” says Marcella Carollo of ETH Zurich, Switzerland, lead author on a new paper exploring these galaxies. “No single collection of images has been large enough to enable us to study very large numbers of galaxies in exactly the same way — until Hubble’s COSMOS,” adds co-author Nick Scoville of Caltech, USA.

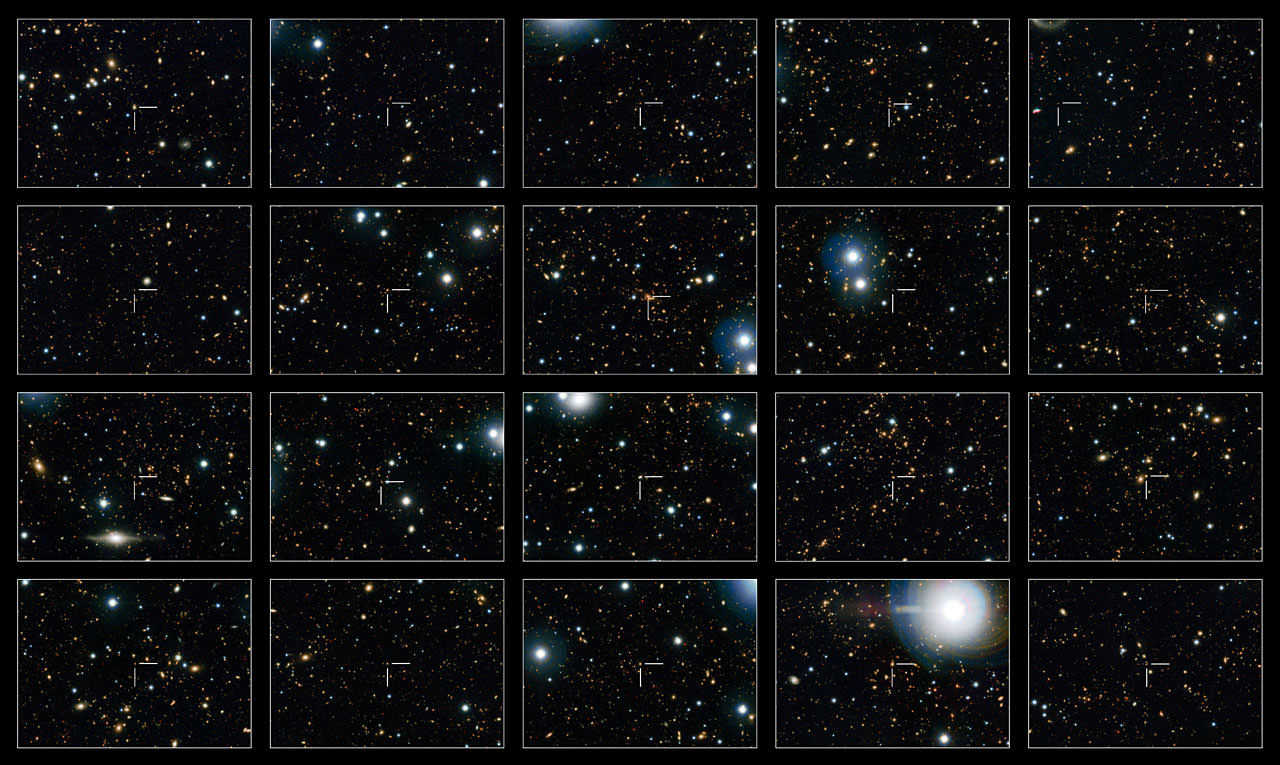

According to the news release, the team utilized a large set of COSMOS images – the product of close to a 1,000 hours of observations and consisting of 575 over-lapped images taken with the Advanced Camera for Surveys (ACS) . Needless to say, it was one of the most ambitious projects ever undertaken by Hubble. The HST data was combined with additional observations from Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope and the Subaru Telescope to look back to when the Universe was about half its present age. This huge data set covered an area of sky almost nine times the size of the full Moon! The saturated – or “quenched” – galaxies present at that age were small and compact… and apparently remained in that state. Instead of getting larger as they evolved, they kept their small size – apparently the same size they were when star-formation ceased. Yet, these galaxy types appear to be gaining in girth as time passes. What gives?

“We found that a large number of the bigger galaxies instead switch off at later times, joining their smaller quenched siblings and giving the mistaken impression of individual galaxy growth over time,” says co-author Simon Lilly, also of ETH Zurich. “It’s like saying that the increase in the average apartment size in a city is not due to the addition of new rooms to old buildings, but rather to the construction of new, larger apartments,” adds co-author Alvio Renzini of INAF Padua Observatory, Italy.

If eight billion years teaches us anything, it teaches us that we don’t know everything…. and sometimes the most simple of answers could be the correct one. We knew that actively star-forming galaxies were far less massive in the early Universe and that explains why they were smaller when star-formation turned off.

“COSMOS provided us with simply the best set of observations for this sort of work — it lets us study very large numbers of galaxies in exactly the same way, which hasn’t been possible before,” adds co-author Peter Capak, also of Caltech. “Our study offers a surprisingly simple and obvious explanation to this puzzle. Whenever we see simplicity in nature amidst apparent complexity, it’s very satisfying,” concludes Carollo.

Original Story Source: ESA/Hubble News Release.