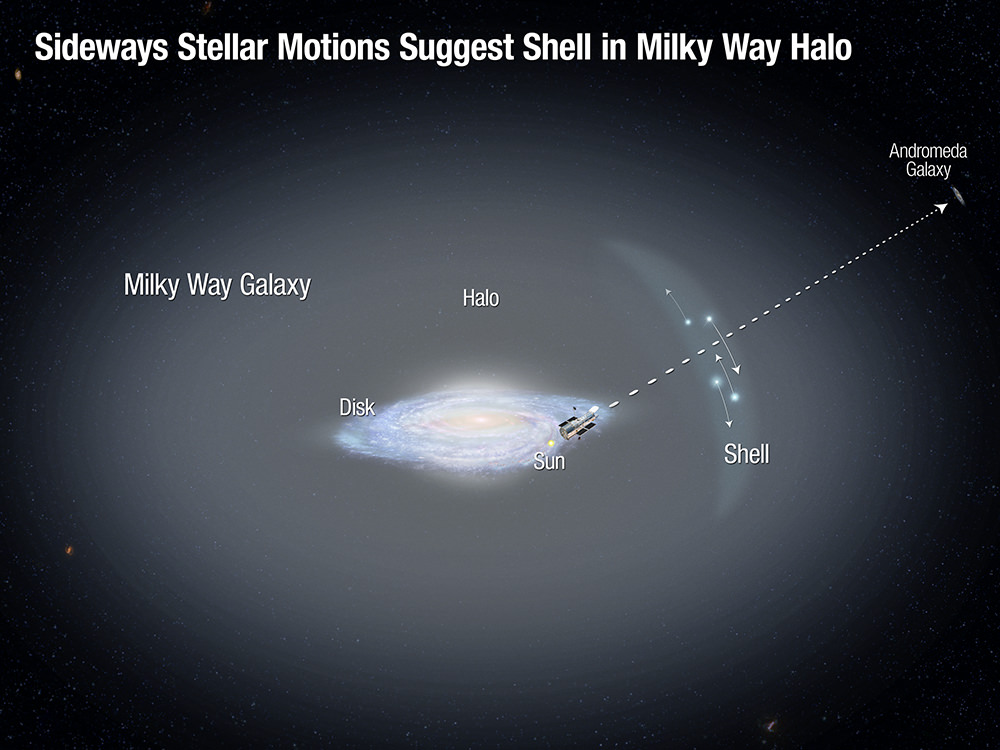

Like tantalizing tidbits stored in the vast recesses of one’s refrigerator, astronomers using NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope have evidence of a shell of stars left over from one of the Milky Way’s meals. In a study which will appear in an upcoming issue of the Astrophysical Journal researchers have revealed a group of stars moving sideways – a motion which points to the fact our galaxy may have consumed another during its evolution.

“Hubble’s unique capabilities are allowing astronomers to uncover clues to the galaxy’s remote past. The more distant regions of the galaxy have evolved more slowly than the inner sections. Objects in the outer regions still bear the signatures of events that happened long ago,” said Roeland van der Marel of the Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI) in Baltimore, Maryland.

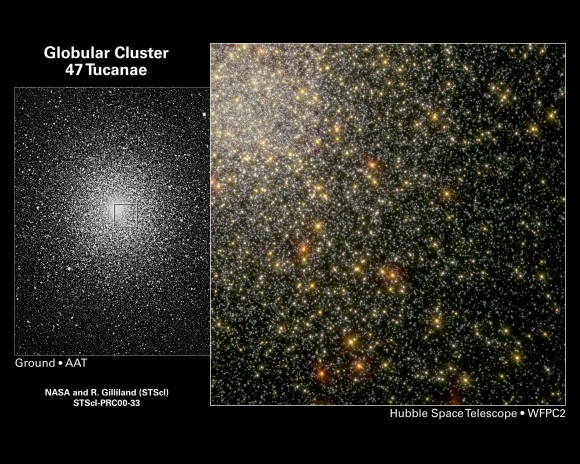

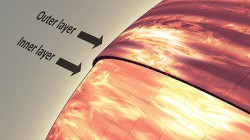

As curious as this shell of stars is, they offer even more information by revealing a chance to study the mysterious hidden mass of Milky Way – dark matter. With more than a hundred billion galaxies spread over the Universe, what better place to get a closer look than right here at home? The team of astronomers led by Alis Deason of the University of California, Santa Cruz, and van der Marel studied the outer halo, a region roughly 80,000 light years from our galaxy’s center, and identified 13 stars which may have come to light at the very beginning of the Milky Way’s formation.

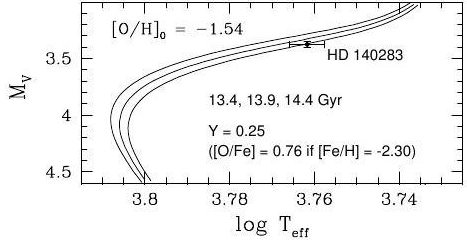

What’s so special about this group of geriatric suns? In this case, it’s their movement. Instead of cruising along in a radial orbit, these elderly stars show tangential motion – an unexpected observation. Normally halo stars travel towards the galactic center, only to return outwards again. What could cause this double handful of stars to move differently? The research team speculates there could be an “over-density” of stars at the 80,000 light year mark.

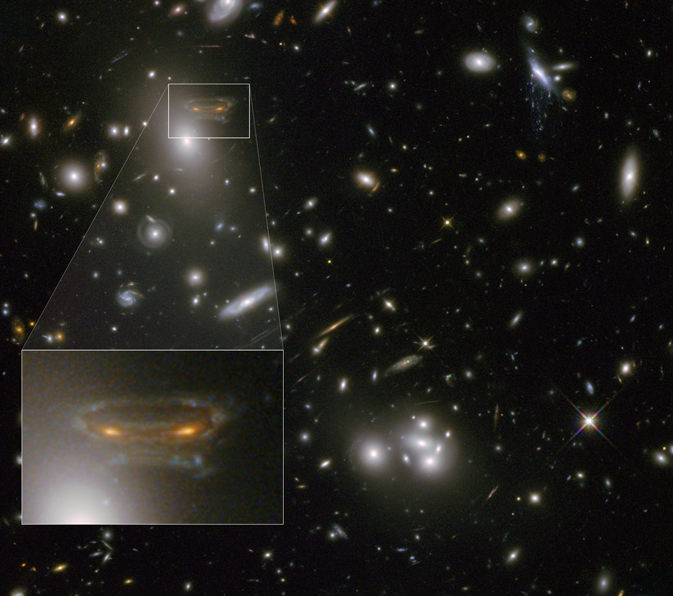

As intriguing as these stars are, this strange shell was discovered somewhat by accident. Deason and her team winnowed out the outer halo stars from a seven year study of archival images taken by the Hubble telescope of the Andromeda galaxy. While looking some twenty times further away at our neighboring galaxy’s stars, these strange moving stars came to light as foreground objects… objects that “cluttered” the images. While these halo stars were bad for that particular study, they were very good for Deason and the team. It gave them the chance to take a really close look at the motion of the Milky Way’s halo stars.

However, seeing these stars wasn’t easy. Thanks to Hubble’s incredible resolution and light gathering power, each image contained more than 100,000 individual stars. “We had to somehow find those few stars that actually belonged to the Milky Way halo,” van der Marel said. “It was like finding needles in a haystack.”

So how did the astronomers separate the shell stars from those that belonged to the outer fringes of the Andromeda? The initial observations picked the stars out based on their color, brightness and sideways motion. Thanks to parallax, our halo stars seem to move far faster simply because they are closer. Through the work of team member Tony Sohn of STSci, these revolutionary stars were identified and measured. Their tangential motion was observed and recorded with five percent precision. Not a speedy process when you consider these shell stars only move across the sky at a rate of about one milliarcsecond per year!

“Measurements of this accuracy are enabled by a combination of Hubble’s sharp view, the many years’ worth of observations, and the telescope’s stability. Hubble is located in the space environment, and it’s free of gravity, wind, atmosphere, and seismic perturbations,” van der Marel said.

What makes the team so confident in their findings? As we know, stars at home in our galaxy’s inner halo have highly radial orbits. When a comparison was made between the sideways motion of the outer halo stars with the inner motions, the researchers found equality. According to computer simulations of galaxy formation, outer stars should continue to have radial motion as they move outward into the halo, but these new findings prove opposite. What could cause it? A natural explanation would be an accretion event involving a satellite galaxy.

To further substantiate their findings, the team compared their results with data taken by the Sloan Digital Sky Survey involving halo stars. It was a eureka moment. The observations taken by the SDSS revealed a higher density of stars at roughly the same distance as the shell-shocked travelers. And the Milky Way isn’t alone. Other studies of halo stars involved in both the Triangulum and Andromeda show a large number of halo stars existing to a certain point – only to drop off. Deason realized this wasn’t just a weird coincidence. “What may be happening is that the stars are moving quite slowly because they are at the apocenter, the farthest point in their orbit about the hub of our Milky Way,” Deason explained. “The slowdown creates a pileup of stars as they loop around in their path and travel back towards the galaxy. So their in and out or radial motion decreases compared with their sideways or tangential motion.”

As exciting as these findings are, they aren’t news. Shell stars have been observed in the halos of other galaxies and were predicted to be part of the Milky Way. By nature, they should have been there – but they were simply to dim and too far-flung to make astronomers positive of their presence. Not any more. Now that astronomers know what to look for, they are even more anxious to dig into Hubble’s archives. “These unexpected results fuel our interest in looking for more stars to confirm that this is really happening,” Deason said. “At the moment we have quite a small sample. So we really can make it a lot more robust with getting more fields with Hubble.” The Andromeda observations only cover a very small “keyhole view” of the sky.

So what’s next? Now the team can paint an even more fine portrait of the Milky Way’s evolutionary history. By understanding the motions and orbits of the “shell” of stars in the halo, they might even by able to give us a accurate mass. “Until now, what we have been missing is the stars’ tangential motion, which is a key component. The tangential motion will allow us to better measure the total mass distribution of the galaxy, which is dominated by dark matter. By studying the mass distribution, we can see whether it follows the same distribution as predicted in theories of structure formation,” Deason said.

Until then we’ll enjoy the “leftovers”…

Original Story Source: HubbleSite News Release.