[/caption]

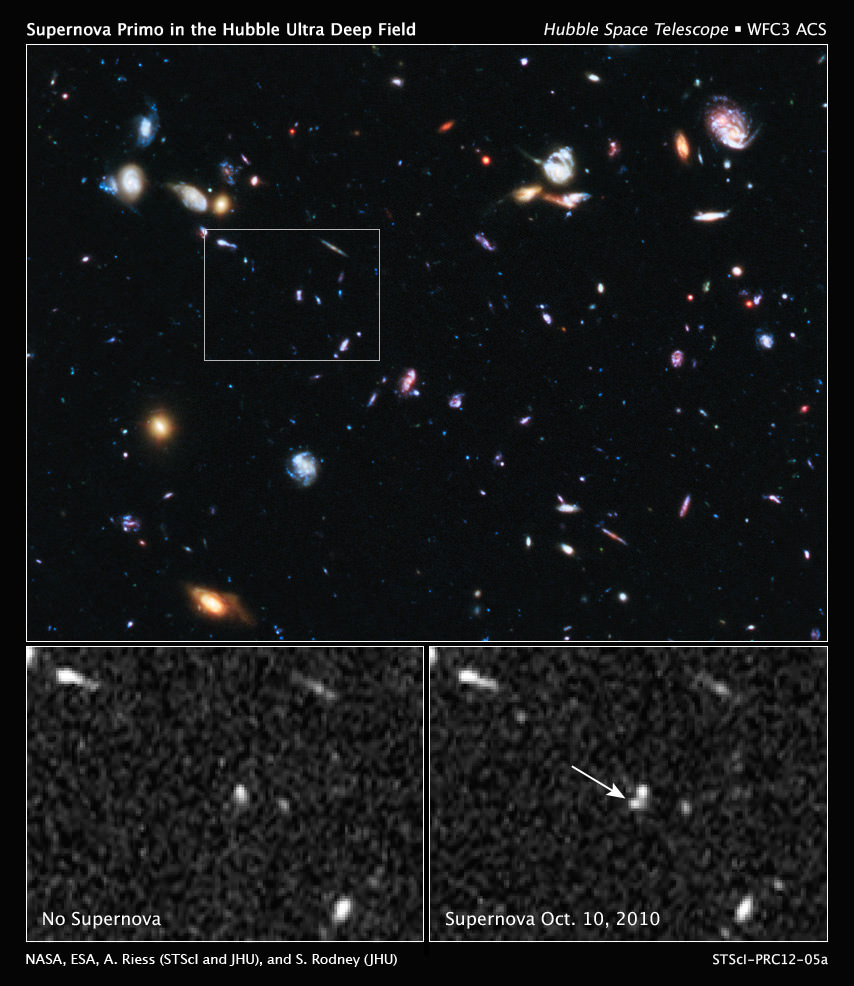

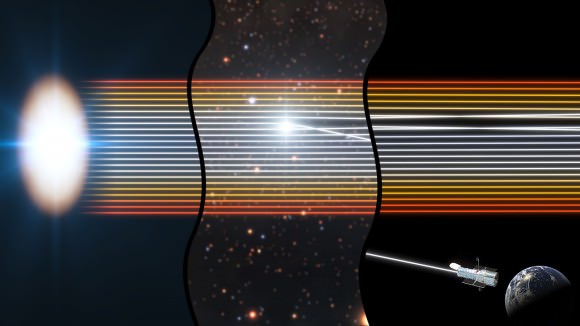

Its nickname is SN Primo and it’s the farthest Type Ia supernova to have its distance spectroscopically confirmed. When the progenitor star exploded some 9 billion years ago, Primo sent its brilliant beacon of light across time and space to be captured by the Hubble Space Telescope. It’s all part and parcel of a three-year project dealing specifically with Type Ia supernovae. By splitting its light into constituent colors, researchers can verify its distance by redshift and help astronomers better understand not only the expanding Universe, but the constraints of dark energy.

“For decades, astronomers have harnessed the power of Hubble to unravel the mysteries of the Universe,” said John Grunsfeld, associate administrator for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate in Washington. “This new observation builds upon the revolutionary research using Hubble that won astronomers the 2011 Nobel Prize in Physics, while bringing us a step closer to understanding the nature of dark energy which drives the cosmic acceleration.”

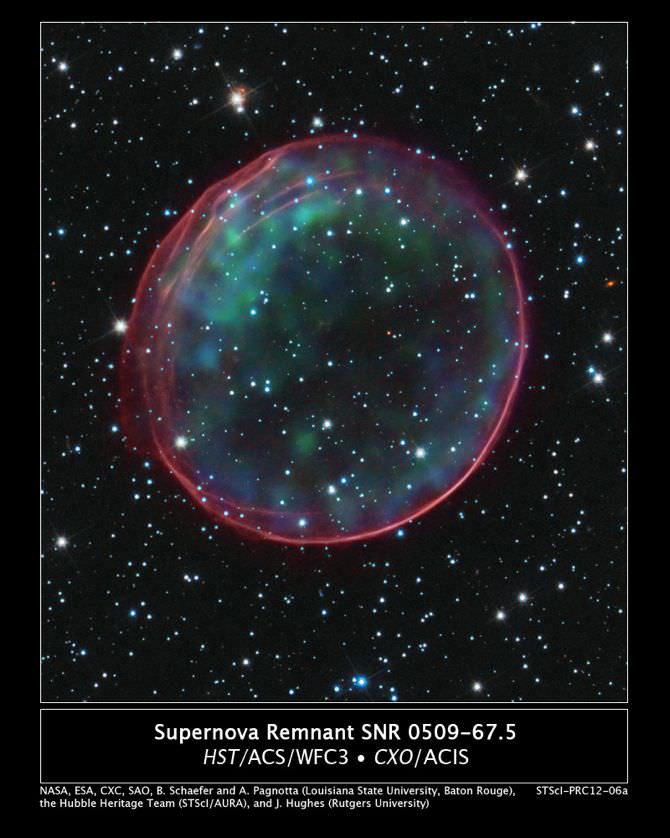

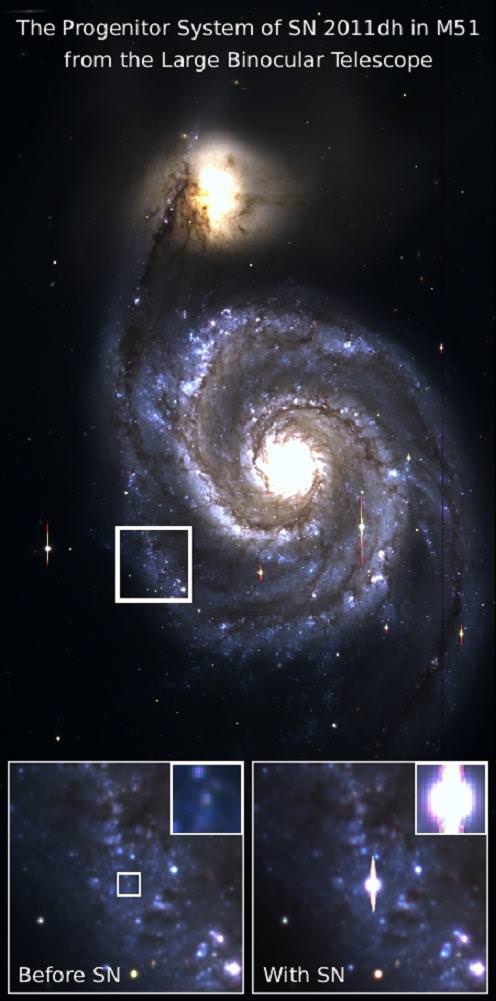

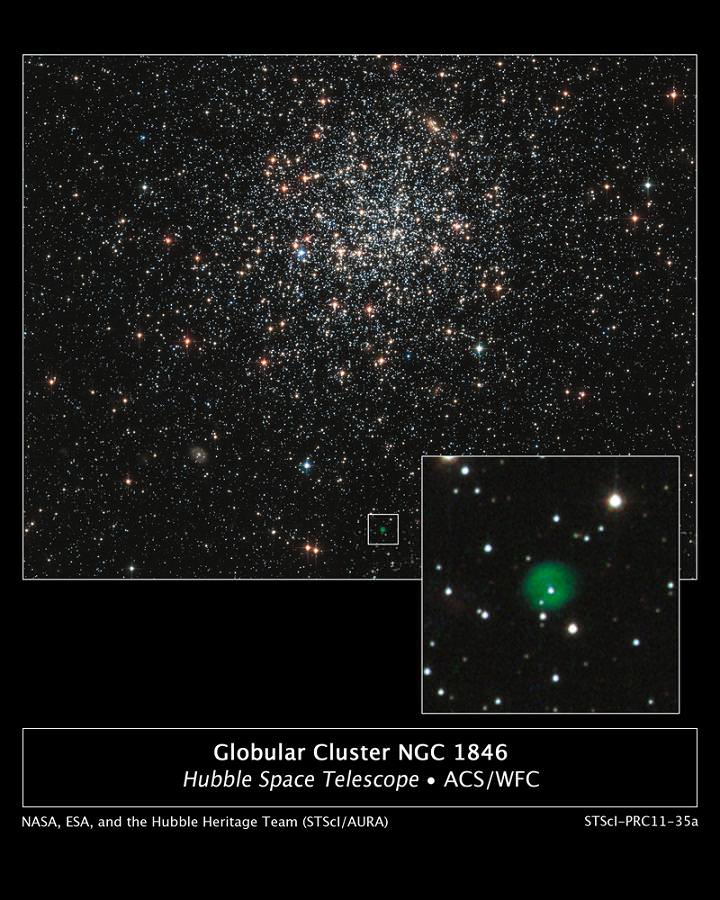

Type Ia supernovae are theorized to have originated from white dwarf stars which have collected an excess of material from their companions and exploded. Because of their remote nature, they have been used to measure great distances with acceptable accuracy. Enter the CANDELS+CLASH Supernova Project… a type of census which utilizes the sharpness and versatility of Hubble’s Wide Field Camera 3 (WFC3) to aid astronomers in the search for supernovae in near- infrared light and verify their distance with spectroscopy. CANDELS is the Cosmic Assembly Near-infrared Deep Extragalactic Legacy Survey and CLASH is the Cluster Lensing and Supernova Survey with Hubble.

“In our search for supernovae, we had gone as far as we could go in optical light,” said Adam Riess, the project’s lead investigator, at the Space Telescope Science Institute and The Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Md. “But it’s only the beginning of what we can do in infrared light. This discovery demonstrates that we can use the Wide Field Camera 3 to search for supernovae in the distant Universe.”

However, discovering a supernova like Primo just doesn’t happen overnight. It took the research team several months of work and a huge amount of near-infrared images to locate the faint signature. After capturing the elusive target in October 2010, it was time to employ the WFC3’s spectrometer to validate SN Primo’s distance and analyze the spectra for confirmation of a Type Ia supernova event. Once verified, the team continued to image SN Primo for the next eight months – collecting data as it faded away. By engaging the Hubble in this type of census, astronomers hope to further their understanding of how such events are created. If they should discover that Type Ia supernova don’t always appear the same, it may lead to a way of categorizing those changes and aid in measuring dark energy. Riess and two other astronomers shared the 2011 Nobel Prize in Physics for discovering dark energy 13 years ago, using Type Ia supernova to plot the Universe’s expansion rate.

“If we look into the early Universe and measure a drop in the number of supernovae, then it could be that it takes a long time to make a Type Ia supernova,” said team member Steve Rodney of The Johns Hopkins University. “Like corn kernels in a pan waiting for the oil to heat up, the stars haven’t had enough time at that epoch to evolve to the point of explosion. However, if supernovae form very quickly, like microwave popcorn, then they will be immediately visible, and we’ll find many of them, even when the Universe was very young. Each supernova is unique, so it’s possible that there are multiple ways to make a supernova.”

Original Story Source: Hubble Site News Release.