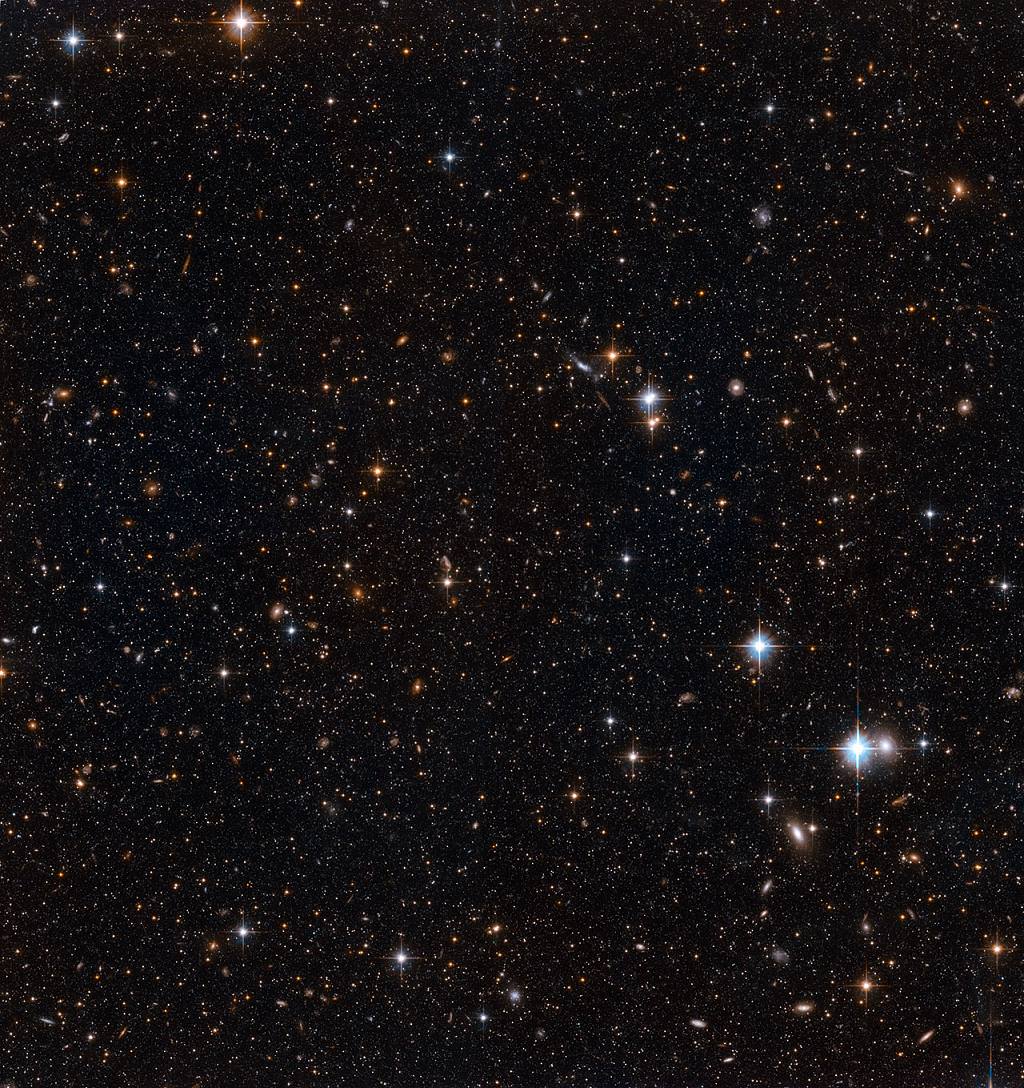

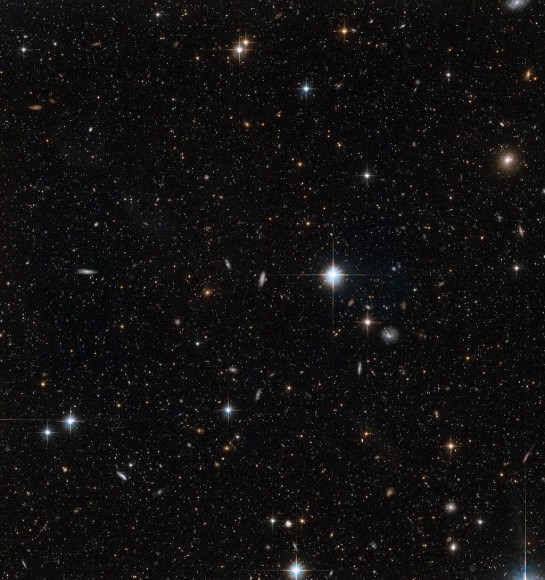

Thanks to Hubble’s Advanced Camera for Surveys, we’re now able to take a deeper look into the Andromeda Galaxy than ever before. Four new images are giving us an unprecedented view of resolved stars – something that just doesn’t occur when looking at other galaxies. Although we can see M31 with unaided vision from a relatively dark sky site, there’s no way we can see the outer regions without a telescope. Now we’re resolving them…

Although astronomers are quite aware that spiral galaxies have great distances between their stellar members, it is one thing to know it and another to see it. High above our atmosphere, the Hubble has a clean view of one of our nearest galactic neighbors, and it’s not looking in a window – it is photographing the backyard. Not only are individual stars revealed, but even more distant galaxies can be seen in the background beyond Andromeda’s dense disc.

[/caption]

But it’s not only there that other galaxies can be seen. Try looking through M31’s halo…

“The two images taken in M 31’s halo show the lowest density of stars. The halo is the huge and sparse sphere of stars that surrounds a galaxy.” says the team. “While there are relatively few stars in a galaxy’s halo, studies of the rotation rate of galaxies suggest that there is a great deal of invisible dark matter.”

But don’t forget the stellar stream. There the stars are more densely packed, causing light extinction – yet the Hubble is resolving them! Take a look at this multitude of stars which could be the remainder of a galaxy M31 absorbed in the past…

“These observations were made in order to observe a wide variety of stars in Andromeda, ranging from faint main sequence stars like our own Sun, to the much brighter RR Lyrae stars, which are a type of variable star.” says the Hubble crew. “With these measurements, astronomers can determine the chemistry and ages of the stars in each part of the Andromeda Galaxy.”

And we can marvel at a look at galaxies which may have remained forever hidden if it weren’t for Hubble’s incredible eye.

Original News Source: ESA / Hubble News.