[/caption]

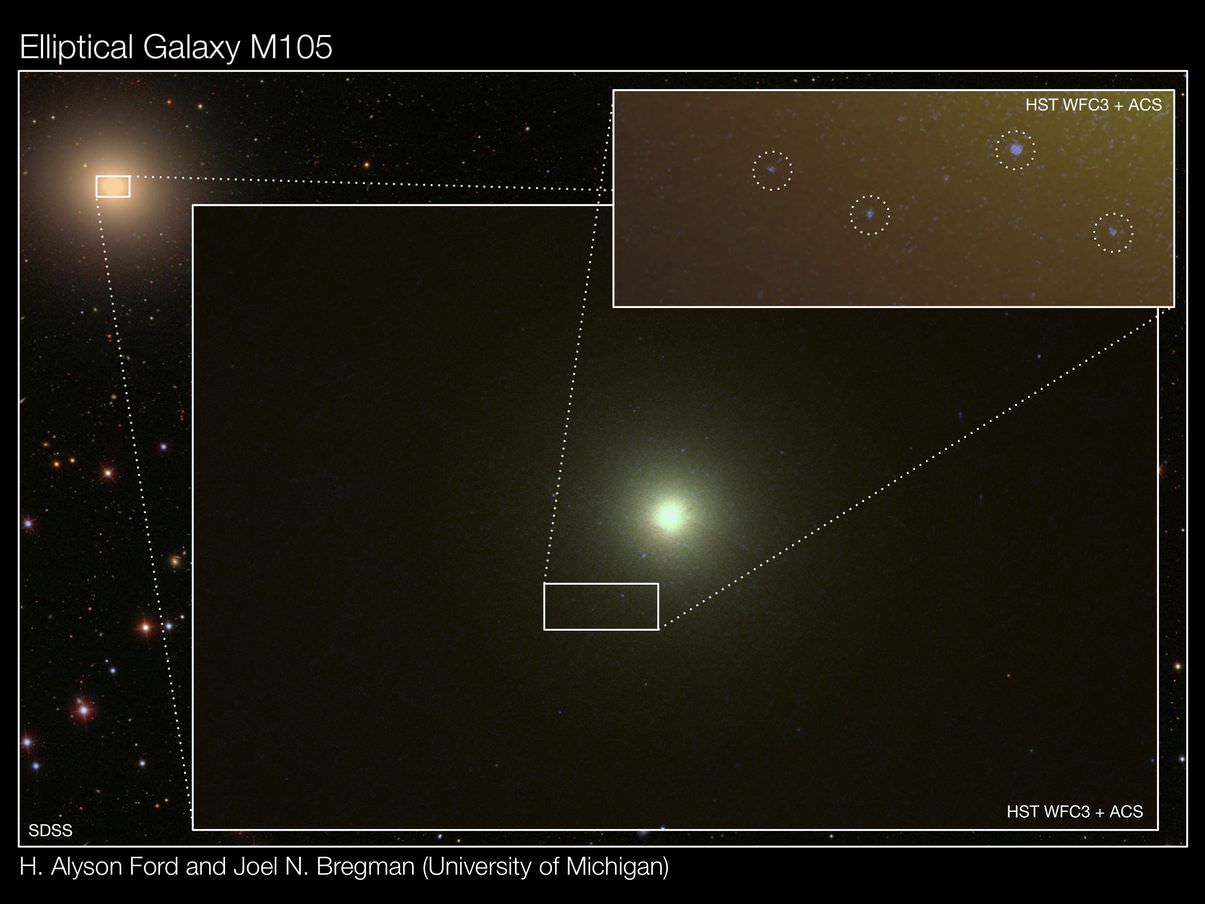

There was a time when most astronomers concluded that elliptical galaxies were a lot like their globular clusters – full of similarly evolved and aged stars. But not anymore. Thanks to the resolving power of the Hubble Space Telescope, a team of researchers from the University of Michigan were able to peer into the heart of Messier 105 and pick out several young stars and clusters. Apparently, “The reports of my death have been greatly exaggerated…”

U-M research fellow Alyson Ford and astronomy professor Joel Bregman are scheduled to present their findings May 31 at a meeting of the Canadian Astronomical Society in London, Ontario. Using the Wide Field Camera 3 on the Hubble Space Telescope, they saw individual young stars and star clusters in four galaxies that are about 40 million light-years away. One light-year is about 5.9 trillion miles.

“Scientists thought these were dead galaxies that had finished making stars a long time ago,” Ford said. “But we’ve shown that they are still alive and are forming stars at a fairly low level.”

We’re all aware of differing galaxy structures, from grand design spirals to disturbed irregulars. However, perhaps one of the most common is the elliptical. Ranging in flat form to nearly spherical, these smooth customers can contain anywhere from hundreds of millions to over one trillion stars – and most of them are believed to be the offspring of galaxy collision. Most elliptical galaxies are composed of older, low-mass stars, with a sparse interstellar medium and minimal star formation activity. Making up somewhere between 10 to 15% of known galaxy population, they are surrounded by globular clusters and usually make their home at the center of galaxy clusters. But what elliptical galaxies aren’t known for is star formation.

“Astronomers previously studied star formation by looking at all of the light from an elliptical galaxy at once, because we usually can’t see individual stars. Our trick is to make sensitive ultraviolet images with the Hubble Space Telescope, which allows us to see individual stars.” said Ford. “”We were confused by some of the colors of objects in our images until we realized that they must be star clusters, so most of the star formation happens in associations.”

The eureka moment came when the team turned the Hubble towards a galaxy most of us have observed on a personal level – M105. Located 38 million light years away in the constellation of Leo and part of the M96 Galaxy Group, this rather ordinary looking elliptical galaxy is one of the brightest to observe. Although there wasn’t any reason to believe star formation was in progress, Ford and Bregman saw a few bright, very blue stars, resembling a single star 10 to 20 times the mass of the Sun. In addition, they also observed objects that aren’t blue enough to be single stars, but instead are clusters of many stars. When accounting for these clusters, stars are forming in Messier 105 at an average rate of one Sun every 10,000 years, Ford and Bregman concluded. “This is not just a burst of star formation but a continuous process,” Ford said.

New stars from a dead galaxy? Maybe it’s a zombie. And it’s not the first time the Hubble has looked its way, either. Investigations of the central region of M105 have revealed that this galaxy contains a massive central object of about 50 million solar masses – a supermassive black hole. Of course, this new evidence creates more questions than it answers and high among the ranks is the origin of the gas that forms the stars.

“We’re at the beginning of a new line of research, which is very exciting, but at times confusing,” Bregman said. “We hope to follow up this discovery with new observations that will really give us insight into the process of star formation in these ‘dead’ galaxies.”

Dead… But maybe not so dead, after all.

Original story source Physorg.com.