[/caption]

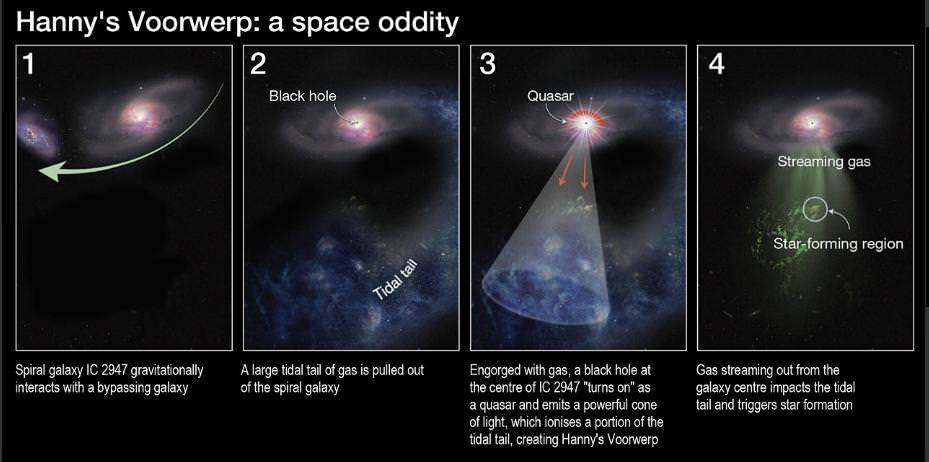

Almost four years ago a group of astronomers known as the Galaxy Zoo made a very exciting discovery – one they named “Hanny’s Voorwerp”. Although the action occurred a hundred thousand years ago and somewhere in the neighborhood of 700 million light years away, a once upon a time quasar burned brighter than its neighboring galaxy. While the tidal pull of massive spiral IC 2497 shredded a gas rich dwarf galaxy, the incredible outpouring of ultraviolet and X-ray radiation combined with the quasar ignited the gases to light… but what exactly is it? The Hubble Space Telescope turned its eye in the direction of Leo Minor to find out…

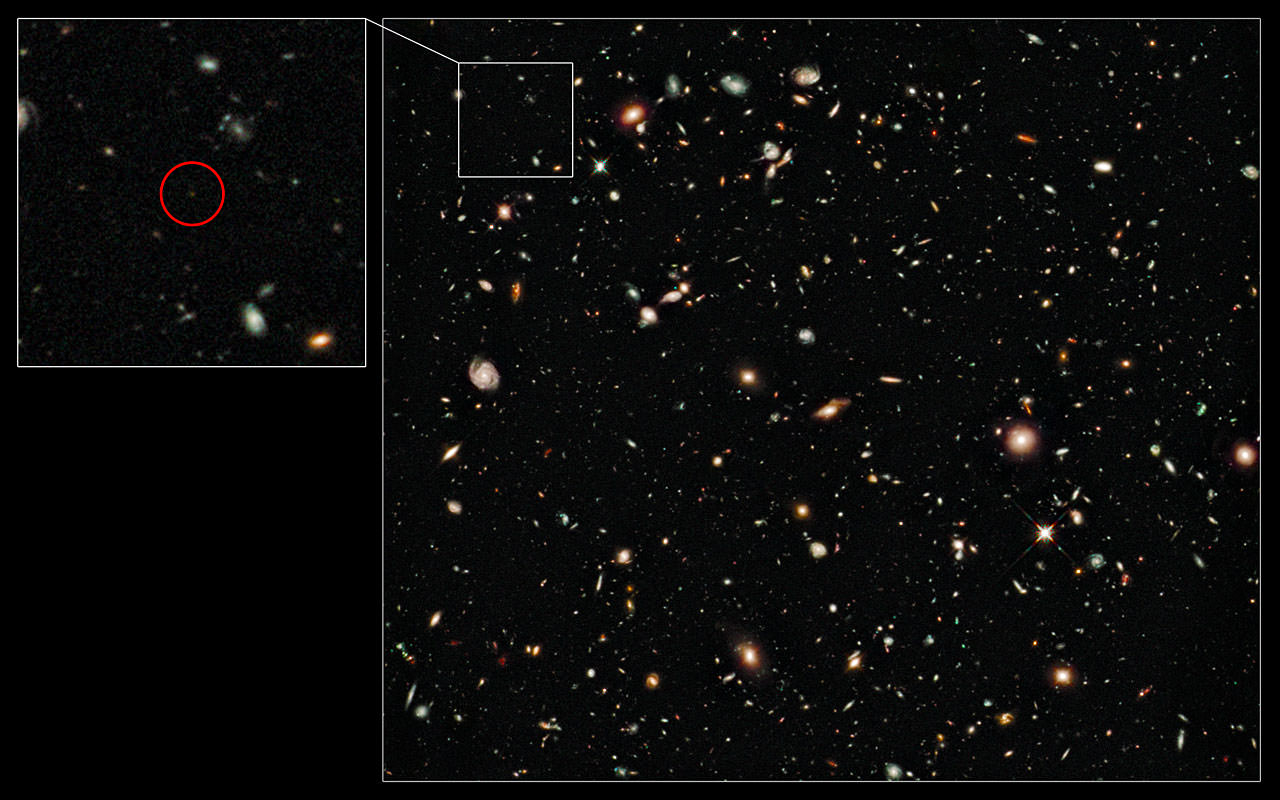

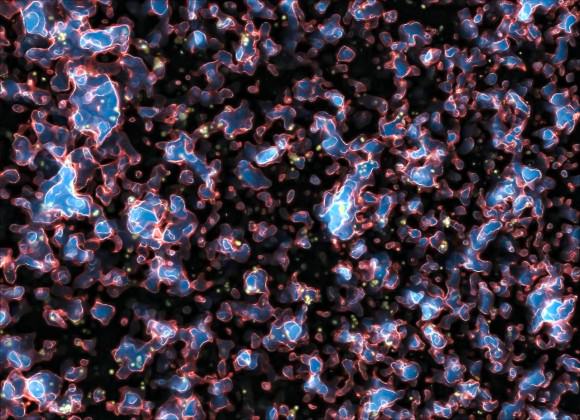

According to the American Astronomical Society press release: “One of the strangest space objects ever seen is being scrutinized by the penetrating vision of the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope. A mysterious, glowing green blob of gas is floating in space near a spiral galaxy. Hubble uncovered delicate filaments of gas and a pocket of young star clusters in the giant object, which is the size of the Milky Way. The Hubble revelations are the latest finds in an ongoing probe of Hannyrquote s Voorwerp (Hanny’s Object in Dutch). It is named after Hanny van Arkel, the Dutch schoolteacher who discovered the ghostly structure in 2007 while participating in the online Galaxy Zoo project. Galaxy Zoo enlists the public to help classify more than a million galaxies catalogued in the Sloan Digital Sky Survey. The project has expanded to include Galaxy Zoo: Hubble, in which the public is asked to assess tens of thousands of galaxies in deep imagery from the Hubble Space Telescope.” In the sharpest view yet of Hanny’s Voorwerp, Hubble’s Wide Field Camera 3 and Advanced Camera for Surveys have uncovered star birth in a region of the green object that faces the spiral galaxy IC 2497 — a bright, energetic object that is powered by a black hole.

This Hubble view reveals new details in colorful clarity – such as a area of star clusters whose members are only a couple of million years old… and the chemically charged yellowish-orange area at the tip of Milky Way sized Hanny’s Voorwerp. The image was made by combining data from the Advanced Camera for Surveys (ACS) and the Wide Field Camera 3 (WFC3) onboard Hubble, with data from the WIYN telescope at Kitt Peak, Arizona, USA. The ACS exposures were taken 12 April 2010; the WFC3 data, 4 April 2010.

“The star clusters are localized, confined to an area that is over a few thousand light-years wide,” explains astronomer William Keel of the University of Alabama in Tuscaloosa, leader of the Hubble study. “The region may have been churning out stars for several million years. They are so dim that they have previously been lost in the brilliant light of the surrounding gas.”

The press release goes on to state that recent X-ray observations have revealed why Hanny’s Voorwerp caught the proverbial eye of astronomers. The galaxy’s rambunctious core produced a quasar, a powerful light beacon powered by a black hole. The quasar shot a broad beam of light in Hanny’s Voorwerp’s direction, illuminating the gas cloud and making it a space oddity. Its bright green color is from glowing oxygen. “We just missed catching the quasar, because it turned off no more than 200,000 years ago, so what we’re seeing is the afterglow from the quasar,” Keel says. “This implies that it might flicker on and off, which is typical of quasars, but we’ve never seen such a dramatic change happen so rapidly.”

The quasar’s outburst also may have cast a shadow on the blob. This feature gives the illusion of a gaping hole about 20,000 light-years wide in Hanny’s Voorwerp. Hubble reveals sharp edges around the apparent opening, suggesting that an object close to the quasar may have blocked some of the light and projected a shadow on Hanny’s Voorwerp. This phenomenon is similar to a fly on a movie projector lens casting a shadow on a movie screen. (Or your little brother Tom making a duck face with his hand while your Mom isn’t looking.) Radio studies have revealed that Hanny’s Voorwerp is not just an island gas cloud floating in space awaiting a three-hour tour. The glowing blob is part of a long, twisting rope of gas, or tidal tail, about 300,000 light-years long that wraps around the galaxy. The only optically visible part of the rope is Hanny’s Voorwerp. The illuminated object is so huge that it stretches from 44,000 light-years to 136,000 light-years from the galaxy’s core. The quasar, the outflow of gas that instigated the star birth, and the long, gaseous tidal tail point to a rough life for IC 2497.

“The evidence suggests that IC 2497 may have merged with another galaxy about a billion years ago,” Keel explains. “The Hubble images show in exquisite detail that the spiral arms are twisted, so the galaxy hasn’t completely settled down.” In Keel’s scenario, the merger expelled the long streamer of gas from the galaxy and funneled gas and stars into the center, which fed the black hole. The engorged black hole then powered the quasar, which launched two cones of light. One light beam illuminated part of the tidal tail, now called Hanny’s Voorwerp.” says Keel. “About a million years ago, shock waves produced glowing gas near the galaxy’s core and blasted it outward. The glowing gas is seen only in Hubble images and spectra. The outburst may have triggered star formation in Hanny’s Voorwerp. Less than 200,000 years ago, the quasar dropped in brightness by 100 times or more, leaving an ordinary-looking core.

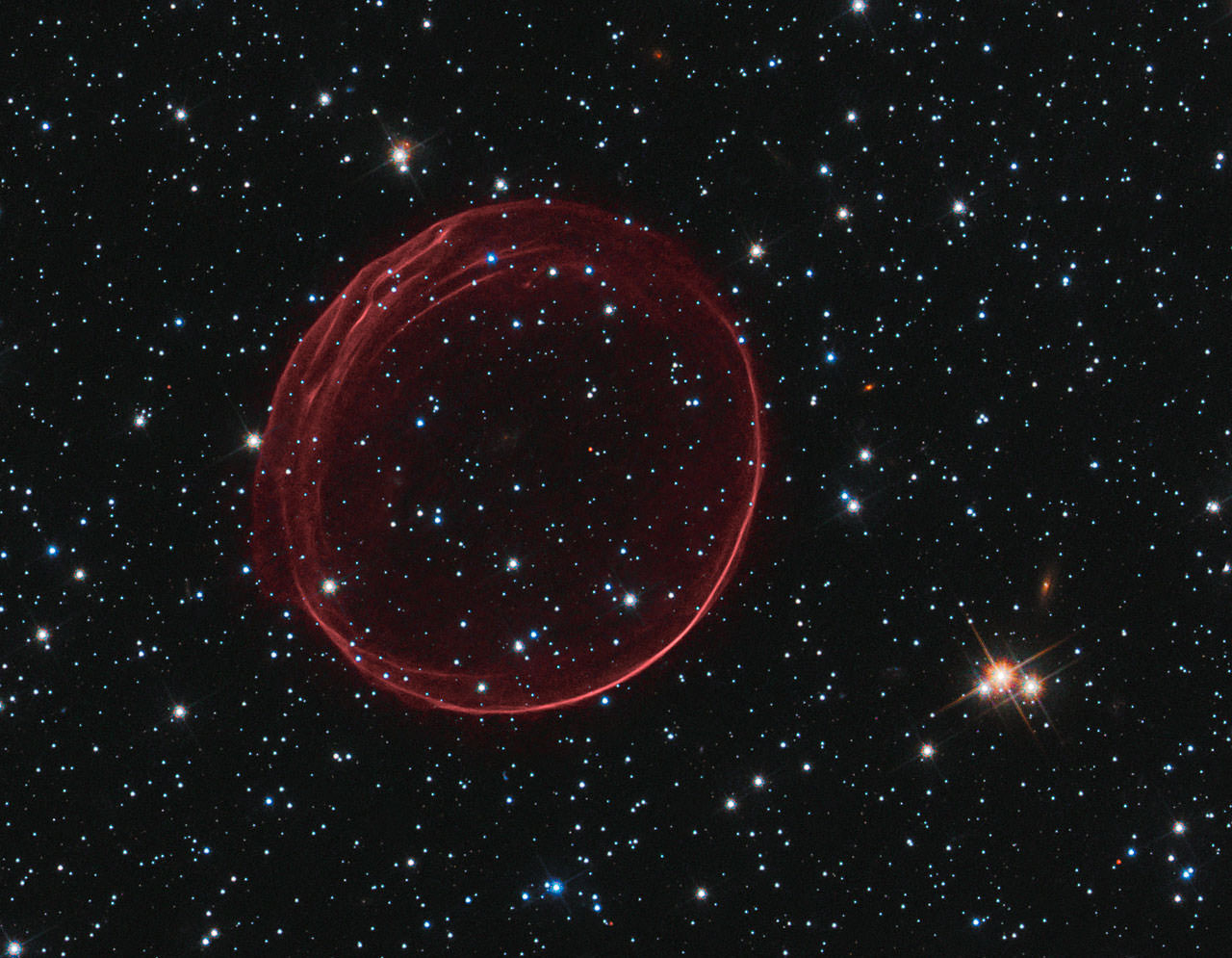

New images of the galaxy’s dusty core from Hubble’s Space Telescope Imaging Spectrograph show an expanding bubble of gas blown out of one side of the core, perhaps evidence of the sputtering quasar’s final gasps. The expanding ring of gas is still too small for ground-based telescopes to detect. “This quasar may have been active for a few million years, which perhaps indicates that quasars blink on and off on timescales of millions of years, not the 100 million years that theory had suggested,” Keel says. He added that the quasar could light up again if more material is dumped around the black hole.

Fascinating evidence which confirms the team’s original explanation… Go Zoo!

Credits: NASA, ESA, William Keel -University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa, the Galaxy Zoo team and STScI Press releases.