[/caption]

Have you heard of ‘living fossils’? The coelacanth, the ginko tree, the platypus, and several others are species alive today which seem to be the same as those found as fossils, in rocks up to hundreds of millions of years old.

Now combined results from the Hubble Space Telescope, Spitzer, Galaxy Evolution Explorer (GALEX), and Swift show that there are ‘living galaxy fossils’ in our own backyard!

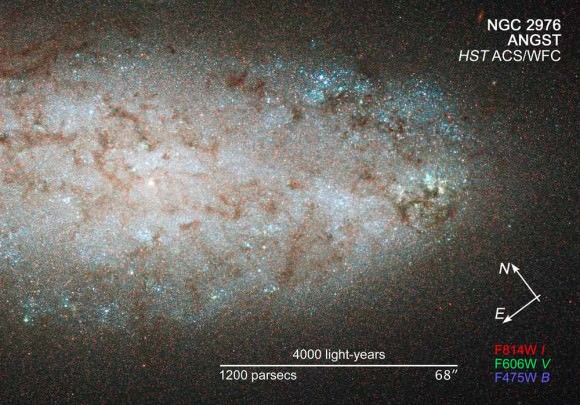

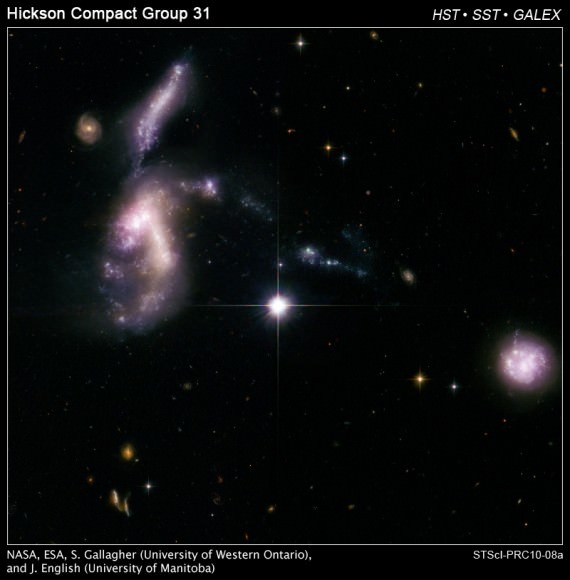

Hickson Compact Group 31 is one of 100 compact galaxy groups catalogued by Canadian astronomer Paul Hickson; the recent study of them – led by Sarah Gallagher of The University of Western Ontario in London, Ontario – shows that the four dwarf galaxies in it are in the process of coming together (or ‘merging’ as astronomers say).

Such encounters between dwarf galaxies are normally seen billions of light-years away and therefore occurred billions of years ago. But these galaxies are relatively nearby, only 166 million light-years away.

New images of this foursome by NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope offer a window into the universe’s formative years when the buildup of large galaxies from smaller building blocks was common.

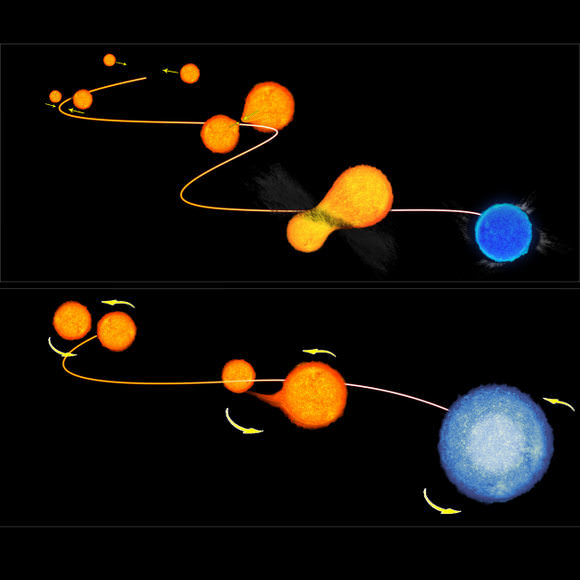

Astronomers have known for decades that these dwarf galaxies are gravitationally tugging on each other. Their classical spiral shapes have been stretched like taffy, pulling out long streamers of gas and dust. The brightest object in the Hubble image is actually two colliding galaxies. The entire system is aglow with a firestorm of star birth, triggered when hydrogen gas is compressed by the close encounters between the galaxies and collapses to form stars.

The Hubble observations have added important clues to the story of this interacting group, allowing astronomers to determine when the encounter began and to predict a future merger.

“We found the oldest stars in a few ancient globular star clusters that date back to about 10 billion years ago. Therefore, we know the system has been around for a while,” says Gallagher; “most other dwarf galaxies like these interacted billions of years ago, but these galaxies are just coming together for the first time. This encounter has been going on for at most a few hundred million years, the blink of an eye in cosmic history. It is an extremely rare local example of what we think was a quite common event in the distant universe.”

In other words, a living fossil.

Everywhere the astronomers looked in this group they found batches of infant star clusters and regions brimming with star birth. The entire system is rich in hydrogen gas, the stuff of which stars are made. Gallagher and her team used Hubble’s Advanced Camera for Surveys to resolve the youngest and brightest of those clusters, which allowed them to calculate the clusters’ ages, trace the star-formation history, and determine that the galaxies are undergoing the final stages of galaxy assembly.

The analysis was bolstered by infrared data from NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope and ultraviolet observations from the Galaxy Evolution Explorer (GALEX) and NASA’s Swift satellite. Those data helped the astronomers measure the total amount of star formation in the system. “Hubble has the sharpness to resolve individual star clusters, which allowed us to age-date the clusters,” Gallagher adds.

Hubble reveals that the brightest clusters, hefty groups each holding at least 100,000 stars, are less than 10 million years old. The stars are feeding off of plenty of gas. A measurement of the gas content shows that very little has been used up – further proof that the “galactic fireworks” seen in the images are a recent event. The group has about five times as much hydrogen gas as our Milky Way Galaxy.

“This is a clear example of a group of galaxies on their way toward a merger because there is so much gas that is going to mix everything up,” Gallagher says. “The galaxies are relatively small, comparable in size to the Large Magellanic Cloud, a satellite galaxy of our Milky Way. Their velocities, measured from previous studies, show that they are moving very slowly relative to each other, just 134,000 miles an hour (60 kilometers a second). So it’s hard to imagine how this system wouldn’t wind up as a single elliptical galaxy in another billion years.”

Adds team member Pat Durrell of Youngstown State University: “The four small galaxies are extremely close together, within 75,000 light-years of each other – we could fit them all within our Milky Way.”

Why did the galaxies wait so long to interact? Perhaps, says Gallagher, because the system resides in a lower-density region of the universe, the equivalent of a rural village. Getting together took billions of years longer than it did for galaxies in denser areas.

Source: HubbleSite News Release. Gallagher et al.’s results appear in the February issue of The Astronomical Journal (the preprint is arXiv:1002.3323)