Self proclaimed “Hubble Hugger” and telescope repairman Dr. John Grunsfeld has been appointed Deputy Director of the Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI) in Baltimore, Maryland, the organization that coordinates all the science done with HST. Grunsfeld’s new job starts today, January 4, 2010. “This is an incredibly exciting opportunity for me to work at a focal point of top astronomers at the leading edge of scientific inquiry. The team at STScI has a demonstrated record of meeting the high performance challenges of operating the Hubble Space Telescope, and preparing for the James Webb Space Telescope. I look forward to working with this excellent team as we continue to explore the mysteries of the universe.”

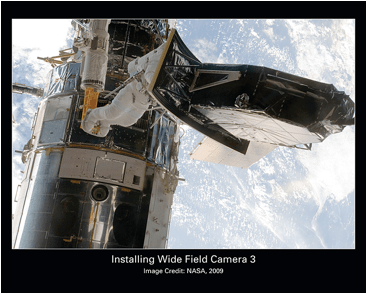

Grunsfeld is a veteran of five space flights, including three missions to service HST: STS-103 in Dec. 1999, STS-109 in March 2002, and STS-125 in May 2009. He has logged over 835 hours in space, including nearly 60 hours of Extravehicular Activity during eight space walks.

He succeeds Dr. Michael Hauser, who stepped down in October. STScI is the science operations center for NASA’s orbiting Hubble Space Telescope and the James Webb Space Telescope planned to be launched in 2014.

Grunsfeld’s research has covered X-ray and gamma-ray astronomy, high-energy cosmic ray studies, and development of new detectors and instrumentation. Grunsfeld has conducted observations of the far-ultraviolet spectra of faint astronomical objects and the polarization of ultraviolet light coming from stars and distant galaxies.

“We are absolutely delighted that he has accepted the position,” said STScI Director, Dr. Matt Mountain. “John brings to us a wealth of expertise in the areas of space exploration concepts and technologies for use beyond low-earth orbit. He will be invaluable in our continued efforts to conduct world-class science with state-of-the-art observatories and instrumentation.

Source: HubbleSite, STSci