NASA officials announced this morning that they were successfully able to restart the Advanced Camera for Surveys on the Hubble Space Telescope. The camera initially failed on June 19 because of power problems. Engineers devised a solution to switch the camera and two other instruments to a backup power system, and began uploading commands on Thursday. The space telescope will resume normal operations on Sunday night.

Continue reading “Hubble Camera is Back Online”

NASA Working on Solution for Hubble’s Camera

NASA officials announced today that the malfunctioning main camera for the Hubble Space Telescope should be back online by July 3. Ground controllers first learned of a problem with the Advanced Camera for Surveys on June 19, when a voltage spike caused the camera to shut down. Officials think a bad transistor might be responsible for the voltage problem, and believe they can resolve the problem without any degradation to Hubble’s performance.

Continue reading “NASA Working on Solution for Hubble’s Camera”

Two Dust Disks Around Beta Pictoris

Detailed photographs of nearby star Beta Pictoris by the Hubble Space Telescope show that it’s circled by two disks of dust. Astronomers believe that a planet with the mass of Jupiter is using its gravity to sweep up material from the primary disk. Additional material is attracted to the planet, and is shaped into a second disk. The dust disk was first discovered by ground telescopes in 1984, and then seen by Hubble in 1995.

Continue reading “Two Dust Disks Around Beta Pictoris”

Extreme Star Birth in Merging Galaxies

The newest image released from the Hubble Space Telescope shows the turbulent region where two galaxies are merging together. The galactic collision is known as Arp 220, and it’s one of the nearest, brightest examples of this in the sky. Hubble’s keen vision has located more than 200 massive star clusters, the largest of which is twice as big as anything we have in the Milky Way. Arp 220 should continue producing new start clusters until it runs out of gas in about 40 million years.

Continue reading “Extreme Star Birth in Merging Galaxies”

Hubble View of NGC 5866

The Hubble Space Telescope captured this magnificent view of disk galaxy NGC 5866, seen nearly edge on from our vantage point. The galaxy’s dark dust lane is clearly visible, and it appears to be slightly warped, compared to the disk of starlight. This indicates that it probably brushed past another galaxy in the distant past. NGC 5866 is located in the constellation Draco, approximately 44 million light-years away; it’s similar in mass to the Milky Way, but only two-thirds the diameter.

Continue reading “Hubble View of NGC 5866”

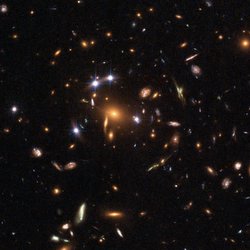

Hubble’s Best Gravitational Lens

Quintuple quasar gravitational lens. Image credit: Hubble. Click to enlarge

The most powerful telescopes in the Universe are relatively nearby galaxies, which warp and focus the light of more distant objects. Called gravitation lenses, which occur randomly, are a boon for astronomers as they allow powerful telescopes, like Hubble, to look even further out into the Universe. This Hubble image is the first “quintuple quasar” ever seen, where an entire galaxy perfectly focuses a more distant quasar – located 12 billion light-years away.

NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope has captured the first-ever picture of a group of five star-like images of a single distant quasar.

The multiple-image effect seen in the Hubble picture is produced by a process called gravitational lensing, in which the gravitational field of a massive object — in this case, a cluster of galaxies — bends and amplifies light from an object — in this case, a quasar — farther behind it.

Although many examples of gravitational lensing have been observed, this “quintuple quasar” is the only case so far in which multiple quasar images are produced by an entire galaxy cluster acting as a gravitational lens.

The background quasar is the brilliant core of a galaxy. It is powered by a black hole, which is devouring gas and dust and creating a gusher of light in the process. When the quasar’s light passes through the gravity field of the galaxy cluster that lies between us and the quasar, the light is bent by the space-warping gravity field in such a way that five separate images of the object are produced surrounding the cluster’s center. The fifth quasar image is embedded to the right of the core of the central galaxy in the cluster. The cluster also creates a cobweb of images of other distant galaxies gravitationally lensed into arcs.

The galaxy cluster creating the lens is known as SDSS J1004+4112 and was discovered in the Sloan Digital Sky Survey. It is one of the more distant clusters known (seven billion light-years away), and is seen as it appeared when the universe was half its present age.

Spectral data taken with the Keck I 10-meter telescope show that these are images of the same galaxy. The spectral results match those inferred by a lens model based only on the image positions and measurements of the light emitted from the quasar.

A gravitational lens will always produce an odd number of lensed images, but one image is usually very weak and embedded deep within the light of the lensing object itself. Though previous observations of SDSS J1004+4112 have revealed four of the images of this system, Hubble’s sharp vision and the high magnification of this gravitational lens combine to place a fifth image far enough from the core of the central imaging galaxy to make it visible as well.

The galaxy hosting the background quasar is at a distance of 10 billion light-years. The quasar host galaxy can be seen in the image as multiple faint red arcs. This is the most highly magnified quasar host galaxy ever seen.

The Hubble picture also shows a large number of stretched arcs that are more distant galaxies lying behind the cluster, each of which is split into multiple distorted images. The most distant galaxy identified and confirmed so far is 12 billion light-years away (corresponding to only 1.8 billion years after the Big Bang).

By comparing this image to a picture of the cluster obtained with Hubble a year earlier, the researchers discovered a rare event — a supernova exploding in one of the cluster galaxies. The supernova exploded seven billion years ago, and the data, together with other supernova observations, are being used to try to reconstruct how the universe was enriched by heavy elements through these explosions.

Original Source: Hubble News Release

Starburst Galaxy M82 by Hubble

Cigar galaxy M82 captured by Hubble. Image credit: NASA/ESA/STScI. Click to enlarge

To celebrate 16 years of observations by the Hubble Space Telescope, NASA and ESA have released this image of galaxy M82 (aka the Cigar Galaxy). Located 12 million light-years away in the constellation Ursa Major, it’s an amazing example of a starburst galaxy. New stars are being born at the heart of M82 at a rate of 10 times what we see in our own Milky Way galaxy. The combined solar winds from all these stars creates a galactic “superwind” that compresses gas further out in the disk and leads to even more star formation.

To celebrate the NASA-ESA Hubble Space Telescope’s 16 years of success, the two space agencies are releasing the sharpest wide-angle view ever obtained of Messier 82 (M82), a galaxy remarkable for its webs of shredded clouds and flame-like plumes of glowing hydrogen blasting out from its central regions.

Located 12 million light-years away, M82 appears high in the northern spring sky in the direction of the constellation Ursa Major, the Great Bear. It is also called the ‘Cigar Galaxy’ because of the elongated elliptical shape produced by the tilt of its starry disk relative to our line of sight.

As shown in this mosaic image, M82 is a magnificent starburst galaxy. Throughout its central region young stars are being born ten times faster than they are inside in our Milky Way Galaxy.

These numerous hot new stars not only emit radiation but also charged particles that form the so-called stellar wind. Stellar winds streaming from these stars combine to form a galactic ‘superwind’.

The superwind compresses enough gas to trigger the ignition of millions more stars and blasts out towering plumes of hot ionised hydrogen gas, above and below the disk of the galaxy (seen in red in the image).

In M82 young stars are crammed into star clusters. These then congregate by the dozen to make the bright patches or ‘starburst clumps’ seen in the central parts of M82. The individual clusters in the clumps can only be distinguished in the ultra-sharp Hubble images.

Most of the pale objects sprinkled around the main body of M82 that look like fuzzy stars are actually star clusters about 20 light-years across and containing up to a million stars.

The rapid rate of star formation in this galaxy will eventually be self-limiting. When star formation becomes too vigorous, it destroys the material needed to make more stars. So the starburst will eventually subside, probably in a few tens of millions of years.

The observation was made in March 2006 with the Advanced Camera for Surveys’ Wide Field Channel. Astronomers assembled the six-image composite mosaic by combining exposures taken with four coloured filters. These capture starlight from visible and infrared wavelengths as well as the light from the glowing hydrogen filaments.

Original Source: ESA News Release

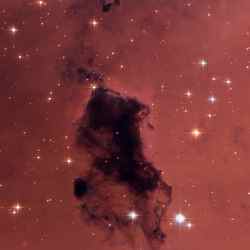

Star Forming Dust Clouds Imaged by Hubble

NGC 281. Image credit: Hubble. Click to enlarge

The dark patch in this Hubble Space Telescope photograph is a “Bok globule” in the nearby star forming region, NGC 281. Astronomer Bart Bok first came up with the theory that dark globules like this are giant clouds of molecular gas, hundreds of light years across. Once perturbed, parts can collapse and become gravitationally bound; eventually forming stars and planets.

The yearly ritual of spring cleaning clears a house of dust as well as dust “bunnies,” those pesky dust balls that frolic under beds and behind furniture. NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope has photographed similar dense knots of dust and gas in our Milky Way Galaxy. This cosmic dust, however, is not a nuisance. It is a concentration of elements that are responsible for the formation of stars in our galaxy and throughout the universe.

These opaque, dark knots of gas and dust are called “Bok globules,” and they are absorbing light in the center of the nearby emission nebula and star-forming region, NGC 281. The globules are named after astronomer Bart Bok, who proposed their existence in the 1940’s.

Bok hypothesized that giant molecular clouds, on the order of hundreds of light-years in size, can become perturbed and form small pockets where the dust and gas are highly concentrated. These small pockets become gravitationally bound and accumulate dust and gas from the surrounding area. If they can capture enough mass, they have the potential of creating stars in their cores; however, not all Bok globules will form stars. Some will dissipate before they can collapse to form stars. That may be what’s happening to the globules seen here in NGC 281.

Near the globules are bright blue stars, members of the young open cluster IC 1590. The cluster is made up of a few hundred stars. The cluster’s core, off the image towards the top, is a tight grouping of extremely hot, massive stars with an immense stellar wind. The stars emit visible and ultraviolet light that energizes the surrounding hydrogen gas in NGC 281. This gas then becomes super heated in a process called ionization, and it glows pink in the image.

The Bok globules in NGC 281 are located very close to the center of the IC 1590 cluster. The exquisite resolution of these Hubble observations shows the jagged structure of the dust clouds as if they are being stripped apart from the outside. The heavy fracturing of the globules may appear beautifully serene but is in fact evident of the harsh, violent environment created by the nearby massive stars.

The Bok globules in NGC 281 are visually striking nonetheless. They are silhouetted against the luminous pink hydrogen gas of the emission nebula, creating a stark visual contrast. The dust knots are opaque in visual light. Conversely, the nebulous gas surrounding the globules is transparent and allows light from background stars and even background galaxies to shine through.

These images were taken with Hubble’s Advanced Camera for Surveys in October 2005. The hydrogen-emission image that clearly shows the outline of the dark globules was combined with images taken in red, blue, and green light in order to help establish the true color of the stars in the field. NGC 281 is located nearly 9,500 light-years away in the direction of the constellation Cassiopeia.

Original Source: HubbleSite News Release

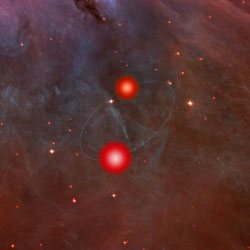

Hubble Pins Down Brown Dwarf Masses

Artist illustration of brown dwarf binary pair. Image credit: Hubble. Click to enlarge.

One of the most difficult tasks for astronomers is to figure out how massive distant objects are. Once you find objects orbiting one another; however, it’s relatively easy to do. The Hubble Space Telescope has helped astronomers measure the mass of a binary pair of brown dwarfs – failed stars – as they orbit one another. One dwarf is 55 times the mass of Jupiter, and the other is 35 times the mass. Each would have to be 80 times the mass of Jupiter before they had enough mass to ignite a fusion reaction.

For the first time, astronomers have succeeded in weighing a binary pair of brown dwarfs and precisely measuring their diameters. These kinds of exact measurements are not possible when observing a single brown dwarf.

Because their orbits are inclined edge-on to Earth, the dwarfs pass in front of each other, creating eclipses. This is the first brown dwarf-eclipsing binary ever discovered. The pair offers an unusual opportunity for accurately determining the masses and diameters of the dwarfs, providing crucial tests of theoretical models.

A brown dwarf is a little understood intermediate class of celestial object that is too small to sustain hydrogen fusion reactions, like those that power our Sun. However, brown dwarfs are dozens of times more massive than the Solar System’s largest planet, Jupiter, and so are too large to be a planet.

The discovery of the paired brown dwarfs and the critical measurements are reported today in the scientific journal Nature by a team of astronomers: Jeff Valenti of the Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI), Robert Mathieu of the University of Wisconsin-Madison, and Keivan Stassun of Vanderbilt University.

One dwarf is 55 times Jupiter’s mass; the other is 35 times heftier than Jupiter (with a 10 percent margin of error). To qualify as a star and burn hydrogen through nuclear fusion, the dwarfs would have to be 80 times more massive than Jupiter. For comparison, the Sun is 1,000 times more massive than Jupiter.

The astronomers are surprised to discover that the more massive brown dwarf is the cooler of the pair, contrary to all predictions about brown dwarfs of the same age. Either the two are not the same age and may be captured bodies, or the theoretical models are wrong, say researchers.

The brown dwarf pair orbits each other so closely that they look like a single object when viewed from Earth. Because their racetrack orbit is edge-on, the two objects periodically pass in front of, or eclipse, each other. These eclipses cause regular dips in the brightness of the combined light coming from both objects. By precisely timing these occultations the astronomers were able to determine the orbits of the two objects. With this information, the astronomers used Newton’s laws of motion to calculate the mass of the two dwarfs.

In addition, the astronomers calculated the size of the two dwarfs by measuring the duration of the dips in their light curve. Because they are so young, the dwarfs are remarkably large for their mass: about the same diameter as the Sun. Because the pair is located in the Orion Nebula, which is a nearby stellar nursery with stars less than 10 million years old.

An analysis of the light coming from the dwarf pair indicates that the dwarfs have a reddish cast. Current models also predict that brown dwarfs should have “weather” — cloud-like bands and spots similar to those visible on Jupiter and Saturn.

By measuring variations in the light spectrum coming from the pair, the astronomers also determined the dwarfs’ surface temperatures. Theory predicts that the more massive member of a pair of brown dwarfs should have a higher surface temperature. But they found just the opposite. The heavier of the two has a temperature of 4,310 degrees Fahrenheit (2,650 degrees Kelvin) and the smaller, 4,562 degrees F (2,790 degrees K). These compare to the Sun’s surface temperature of 9,980 degrees F (5,800 degrees K).

“One possible explanation is that the two objects have different origins and ages,” Stassun says. If that is the case, then it supports one of the outcomes of the latest efforts to simulate the star-formation process. These simulations predict that brown dwarfs are created so close together that they are likely to disrupt each other’s formation.

The new observations confirm the theoretical prediction that brown dwarfs start out as star-sized objects, but shrink and cool and become increasingly planet-sized as they age. Before now, the only brown dwarf whose mass had been directly measured was much older and dimmer.

Many astronomers think that brown dwarfs may actually be the most common product of the stellar-formation process. So, information about brown dwarfs can provide valuable new insights into the dynamic processes that produce stars out of collapsing whirlpools of interstellar dust and gas.

Because old brown dwarfs are smaller and dimmer than true stars, it is only in recent years that improvements in telescope technology have allowed astronomers to catalog hundreds of faint objects that they think may be brown dwarfs. But to pick out the brown dwarfs from other types of faint objects, they need a way to estimate their masses, because mass is destiny for stars and star-like objects.

The existence of brown dwarfs was first proposed in the 1980s, but it wasn’t until 2000 that a brown dwarf was detected unambiguously. While brown dwarfs were hypothetical objects, astronomers differentiated them from planets by the manner in which they formed. Brown dwarfs and stars are formed in the same way, from a collapsing cloud of interstellar dust and gas. Planets are built from the disks of dust and gas that surround forming stars. Once astronomers discovered the first candidate brown dwarf, they realized that dwarfs are very difficult to differentiate from planets, particularly when they have stellar companions. So a growing group of astronomers favor defining brown dwarfs as objects between 13 to 80 times more massive than Jupiter.

The researchers made the observations with two sets of telescopes located in the Chilean Andes, about 100 miles north of Santiago: the Small and Moderate Aperture Research Telescope System (SMARTS), operated by a consortium including the Space Telescope Science Institute and Vanderbilt University, and the International Gemini Observatory, operated by the National Science Foundation.

Original Source: Hubble News Release

Hubble Portrait of the Pinwheel Galaxy

Spiral galaxy M101. Image credit: NASA/ESA Click to enlarge

This amazing photograph of galaxy M101 (also known as the Pinwheel Galaxy) was taken by the Hubble Space Telescope – it’s the largest and most detailed photo ever taken of this galaxy. The photo is actually composed of 51 separate Hubble exposures, stitched together on computer. M101 is one of the most popular galaxies for astronomers, because it’s seen perfectly face on. You can see the incredible spiraling arms containing dust, stars and large regions of star forming nebulae.

Giant galaxies weren’t assembled in a day. Neither was this Hubble Space Telescope image of the face-on spiral galaxy Messier 101 (M101). It is the largest and most detailed photo of a spiral galaxy that has ever been released from Hubble. The galaxy’s portrait is actually composed of 51 individual Hubble exposures, in addition to elements from images from ground-based photos. The final composite image measures a whopping 16,000 by 12,000 pixels.

The Hubble archived observations that went into assembling this image were originally acquired for a range of Hubble projects: determining the expansion rate of the universe, studying the formation of star clusters in the giant star birth regions, finding the stars responsible for intense X-ray emission, and discovering blue supergiant stars.

The giant spiral disk of stars, dust, and gas is 170,000 light-years across or nearly twice the diameter of our galaxy, the Milky Way. M101 is estimated to contain at least one trillion stars. Approximately 100 billion of these stars could be like our Sun in terms of temperature and lifetime.

The galaxy’s spiral arms are sprinkled with large regions of star-forming nebulae. These nebulae are areas of intense star formation within giant molecular hydrogen clouds. Brilliant young clusters of hot, blue, newborn stars trace out the spiral arms. The disk of M101 is so thin that Hubble easily sees many more distant galaxies lying behind the galaxy.

M101 (also nicknamed the Pinwheel Galaxy) lies in the northern circumpolar constellation, Ursa Major (The Great Bear), at a distance of 25 million light-years from Earth. Therefore, we are seeing the galaxy as it looked 25 million years ago – when the light we’re receiving from it now was emitted by its stars – at the beginning of Earth’s Miocene Period, when mammals flourished and the Mastodon first appeared on Earth. The galaxy fills a region in the sky equal to one-fifth the area of the full moon.

The newly composed image was assembled from Hubble archived images taken with the Advanced Camera for Surveys and the Wide Field and Planetary Camera 2 over nearly 10 years: in March 1994, September 1994, June 1999, November 2002, and January 2003. The Hubble exposures have been superimposed onto ground-based images, visible at the edge of the image, taken at the Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope in Hawaii, and at the 0.9-meter telescope at Kitt Peak National Observatory, part of the National Optical Astronomy Observatory in Arizona. The final color image was assembled from individual exposures taken through blue, green, and red (infrared) filters.

Original Source: HubbleSite News Release