Image credit: Hubble

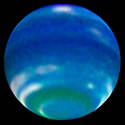

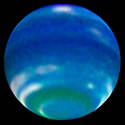

New photos of Neptune taken by the Hubble Space Telescope seem to indicate that the planet is entering its version of Spring. By comparing photos taken in 1996, astronomers believe that bands across the planet are getting wider and brighter, which seems to be a response to increased sunlight. Like the Earth, Neptune is believed to have four seasons, but since the planet takes 165 years to orbit the Sun, they last decades, not months.

Springtime is blooming on Neptune! This might sound like an oxymoron because Neptune is the farthest and coldest of the major planets. But NASA Hubble Space Telescope observations are revealing an increase in Neptune’s brightness in the southern hemisphere, which is considered a harbinger of seasonal change, say astronomers.

Observations of Neptune made over six years by a group of scientists from the University of Wisconsin-Madison and NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) show a distinct increase in the amount and brightness of the banded cloud features located mostly in the planet’s southern hemisphere.

“Neptune’s cloud bands have been getting wider and brighter,” says Lawrence A. Sromovsky, a senior scientist at University of Wisconsin- Madison’s Space Science and Engineering Center and a leading authority on Neptune’s atmosphere. “This change seems to be a response to seasonal variations in sunlight, like the seasonal changes we see on Earth.”

The findings are reported in the current issue (May, 2003) of Icarus, a leading planetary science journal.

Neptune, the eighth planet from the Sun, is known for its weird and violent weather. It has massive storm systems and ferocious winds that sometimes gust to 900 miles per hour, but the new Hubble observations are the first to suggest that the planet undergoes a change of seasons.

Using Hubble, the Wisconsin team made three sets of observations of Neptune. In 1996, 1998, and 2002, observations of a full rotation of the planet were obtained. The images showed progressively brighter bands of clouds encircling the planet’s southern hemisphere. The findings are consistent with observations made by G.W. Lockwood at the Lowell Observatory, which show that Neptune has been gradually getting brighter since 1980.

Neptune’s near-infrared brightness is much more sensitive to high altitude clouds than its visible brightness. The recent trend of increasing cloud activity on Neptune has been qualitatively confirmed at near-infrared wavelengths with Keck Telescope observations from July 2000 to June 2001 by H. Hammel and co-workers. Near-infrared observations at NASA’s Infrared Telescope Facility on Mauna Kea, Hawaii are planned for this summer to further characterize changes in the high-altitude cloud structure.

“In the 2002 images, Neptune is clearly brighter than it was in 1996 and 1998,” Sromovsky says, “and is dramatically brighter at near infrared wavelengths. The greatly increased cloud activity in 2002 continues a trend first noticed in 1998.”

Like the Earth, Neptune would have four seasons: “Each hemisphere would have a warm summer and a cold winter, with spring and fall being transitional seasons, which may or may not have specific dynamical features,” the Wisconsin scientist explains.

Unlike the Earth, however, the seasons of Neptune last for decades, not months. A single season on the planet, which takes almost 165 years to orbit the Sun, can last more than 40 years. If what scientists are observing is truly seasonal change, the planet will continue to brighten for another 20 years.

Also like Earth, Neptune spins on an axis that is tilted at an angle toward the Sun. The tilt of the Earth, at a 23.5-degree inclination, is the phenomenon responsible for the change of seasons. As the Earth orbits the Sun over the course of a year, the planet is exposed to patterns of solar radiation that mark the seasons. Similarly, Neptune is inclined at a 29-degree angle and the northern and southern hemispheres alternate in their positions relative to the Sun.

What is remarkable, according to Sromovsky, is that Neptune exhibits any evidence of seasonal change at all, given that the Sun, as viewed from the planet, is 900 times dimmer than it is from Earth. The amount of solar energy a hemisphere receives at a given time is what determines the season.

“When the Sun deposits heat energy into an atmosphere, it forces a response. We would expect heating in the hemisphere getting the most sunlight. This in turn could force rising motions, condensation and increased cloud cover,” Sromovsky notes.

Bolstering the idea that the Hubble images are revealing a real increase in Neptune’s cloud cover consistent with seasonal change is the apparent absence of change in the planet’s low latitudes near its equator.

“Neptune’s nearly constant brightness at low latitudes gives us confidence that what we are seeing is indeed seasonal change as those changes would be minimal near the equator and most evident at high latitudes where the seasons tend to be more pronounced.”

Despite the new insights into Neptune, the planet remains an enigma, says Sromovsky. While Neptune has an internal heat source that may also contribute to the planet’s apparent seasonal variations and blustery weather, when that is combined with the amount of solar radiation the planet receives, the total is so small that it is hard to understand the dynamic nature of Neptune’s atmosphere.

There seems, Sromovsky says, to be a “trivial amount of energy available to run the machine that is Neptune’s atmosphere. It must be a well-lubricated machine that can create a lot of weather with very little friction.”

In addition to Sromovsky, authors of the Icarus paper include Patrick M. Fry and Sanjay S. Limaye, both of University of Wisconsin-Madison’s Space Science and Engineering Center; and Kevin H. Baines of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif.

Original Source: Hubble News Release